NEUTRON STARS

One of the great predictions of astronomy based on the physical properties of matter was made by a young physicist/astronomer S. Chandrasekhar in the 1930s. With some relatively straightforward calculations, Chandrasekhar predicted that if a cooling, collapsing star had a mass greater than 1.4 times the mass of the sun, the force of gravity would be strong enough to cram the atomic electrons down into the nuclei, converting the protons to neutrons, leaving behind a ball of neutrons about 10 miles in diameter.

Chandrasekhar talked about this idea with his sponsor Sir Arthur Eddington, who was, at the time, one of the most famous astronomers in the world. In private, Eddington agreed with Chandrasekhar’s calculations, but when asked about them in the 1932 meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society, Eddington replied that he did not believe that such a process could possibly occur. Chandrasekhar’s ideas were dismissed by the astronomical community, and a discouraged Chandrasekhar left astronomy and went into the field of hydrodynamics and plasma physics where he made significant contributions.

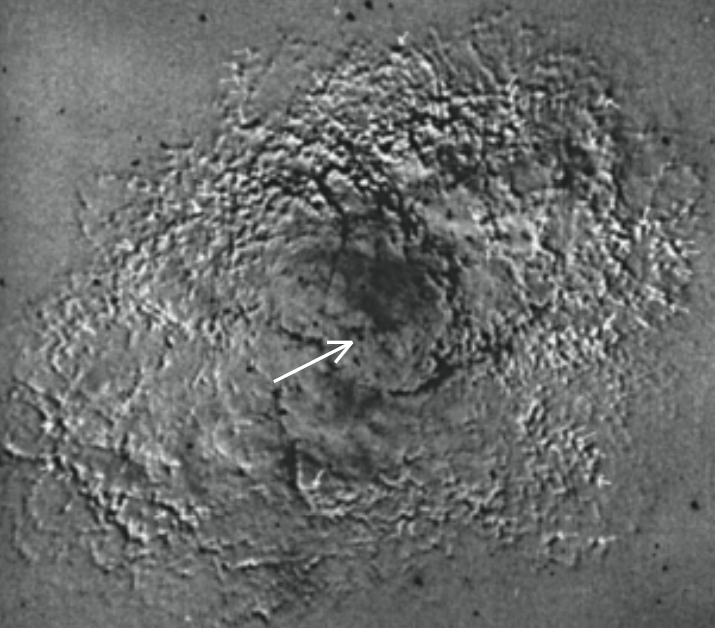

Figure 1a: The Crab Nebula. The arrow points to the pulsar that created the nebula.

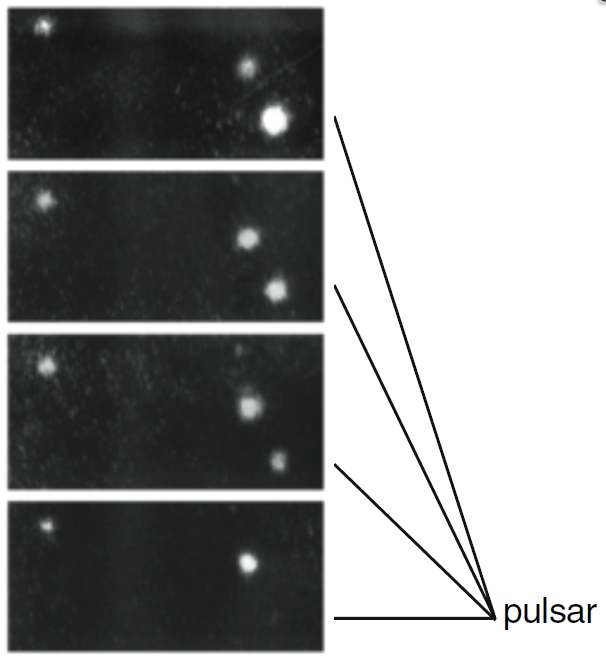

Figure 1b: Expansion of the Crab Nebula. Two photographs, taken 14 years apart, the first printed in white, the second dark, show the expansion centered on the pulsar.

In 1967, the graduate student Jocelyn Bell, using equipment devised by Antony Hewish, observed an object emitting extremely sharp radio pulses that were 1.337 seconds apart. By the end of the year, up to ten such pulsing objects were detected, one with pulses only 89 milliseconds apart. After eliminating the possibility that the radio pulse was communication from an advanced civilization, it was determined that the signals were most likely from an objects rotating at high speeds. A star cannot rotate that fast unless it is very compact, less than 100 miles in diameter. The only candidate for such an object was Chandresekhar’s neutron star.

Many other pulsing stars—pulsars—have been discovered. The closest sits at the center of the explosion that created the Crab Nebula seen in Figure (1a). A superposition of photographs taken in 1950 and 1964, Figure (1b), shows that the gas in the Crab Nebula is expanding away from the star marked with an arrow. Taking a high speed moving picture of this star, something that one does not usually do when photographing stars, shows that this star turns on and off 33 times a second as seen in Figure (2). This is the neutron star left behind when the supernova exploded.

Figure 2: Neutron star in Crab Nebula, turns on and off 33 times/sec.

We have now been able to study many pulsars, and know that the typical neutron star is a ball of neutrons about 10 miles in diameter, rotating at rates up to nearly 1000 revolutions per second! We can detect neutron stars because they have a bright spot that emits a beam of radiation. We see the pulses of radiation when the beam sweeps over us much as the captain of a ship sees the bright flash from a lighthouse when the beam sweeps past.

Computer models suggest that the bright spot is created by the magnetic field of the star, a field that was tied to the material in the core of the star and was strengthened as the core collapsed. Charged particles in the ‘atmosphere’ of the neutron star spiral around the magnetic field lines striking the star at the magnetic poles. On the earth, charged particles spiraling around the earth’s magnetic field lines strike the earth’s atmosphere at the magnetic poles, creating the aurora borealis and aurora australis, the northern and southern lights that light up extreme northern and southern night skies. On a neutron star, the aurora is much brighter, also the atmosphere much thinner, only a few centimeters thick. (In Chapter 28 on Magnetism, we will talk about the motion of charged particles in a magnetic field.)

الاكثر قراءة في النجوم

الاكثر قراءة في النجوم

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة