تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Locating the center of mass

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 19

2024-03-01

1361

The mathematical techniques for the calculation of centers of mass are in the province of a mathematics course, and such problems provide good exercise in integral calculus. After one has learned calculus, however, and wants to know how to locate centers of mass, it is nice to know certain tricks which can be used to do so. One such trick makes use of what is called the theorem of Pappus. It works like this: if we take any closed area in a plane and generate a solid by moving it through space such that each point is always moved perpendicular to the plane of the area, the resulting solid has a total volume equal to the area of the cross section times the distance that the center of mass moved! Certainly, this is true if we move the area in a straight line perpendicular to itself, but if we move it in a circle or in some other curve, then it generates a rather peculiar volume. For a curved path, the outside goes around farther, and the inside goes around less, and these effects balance out. So, if we want to locate the center of mass of a plane sheet of uniform density, we can remember that the volume generated by spinning it about an axis is the distance that the center of mass goes around, times the area of the sheet.

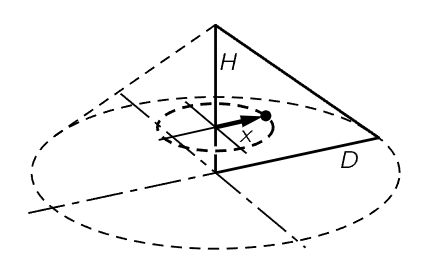

Fig. 19–2. A right triangle and a right circular cone generated by rotating the triangle.

For example, if we wish to find the center of mass of a right triangle of base D and height H (Fig. 19–2), we might solve the problem in the following way. Imagine an axis along H, and rotate the triangle about that axis through a full 360 degrees. This generates a cone. The distance that the x-coordinate of the center of mass has moved is 2πx. The area which is being moved is the area of the triangle, 1/2 HD. So the x-distance of the center of mass times the area of the triangle is the volume swept out, which is of course πD2H/3. Thus (2πx)(1/2 HD)=πD2H/3, or x=D/3. In a similar manner, by rotating about the other axis, or by symmetry, we find y=H/3. In fact, the center of mass of any uniform triangular area is where the three medians, the lines from the vertices through the centers of the opposite sides, all meet. That point is 1/3 of the way along each median. Clue: Slice the triangle up into a lot of little pieces, each parallel to a base. Note that the median line bisects every piece, and therefore the center of mass must lie on this line.

Now let us try a more complicated figure. Suppose that it is desired to find the position of the center of mass of a uniform semicircular disc—a disc sliced in half. Where is the center of mass? For a full disc, it is at the center, of course, but a half-disc is more difficult. Let r be the radius and x be the distance of the center of mass from the straight edge of the disc. Spin it around this edge as axis to generate a sphere. Then the center of mass has gone around 2πx, the area is πr2/2 (because it is only half a circle). The volume generated is, of course, 4πr3/3, from which we find that

There is another theorem of Pappus which is a special case of the above one, and therefore equally true. Suppose that, instead of the solid semicircular disc, we have a semicircular piece of wire with uniform mass density along the wire, and we want to find its center of mass. In this case there is no mass in the interior, only on the wire. Then it turns out that the area which is swept by a plane curved line, when it moves as before, is the distance that the center of mass moves times the length of the line. (The line can be thought of as a very narrow area, and the previous theorem can be applied to it.)