تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

The human eye

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 35

2024-03-30

1904

The phenomenon of colors depends partly on the physical world. We discuss the colors of soap films and so on as being produced by interference. But also, of course, it depends on the eye, or what happens behind the eye, in the brain. Physics characterizes the light that enters the eye, but after that, our sensations are the result of photochemical-neural processes and psychological responses.

There are many interesting phenomena associated with vision which involve a mixture of physical phenomena and physiological processes, and the full appreciation of natural phenomena, as we see them, must go beyond physics in the usual sense. We make no apologies for making these excursions into other fields, because the separation of fields, as we have emphasized, is merely a human convenience, and an unnatural thing. Nature is not interested in our separations, and many of the interesting phenomena bridge the gaps between fields.

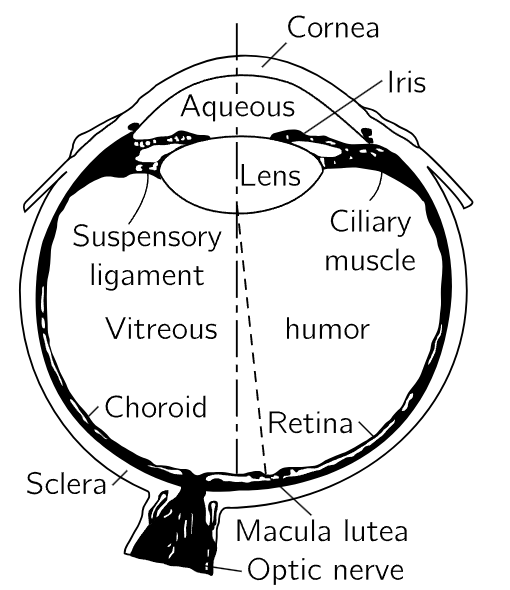

It all begins with the eye; so, in order to understand what phenomena we see, some knowledge of the eye is required. In the next chapter we shall discuss in some detail how the various parts of the eye work, and how they are interconnected with the nervous system. For the present, we shall describe only briefly how the eye functions (Fig. 35–1).

Fig. 35–1. The eye.

Light enters the eye through the cornea; we have already discussed how it is bent and is imaged on a layer called the retina in the back of the eye, so that different parts of the retina receive light from different parts of the visual field outside. The retina is not absolutely uniform: there is a place, a spot, in the center of our field of view which we use when we are trying to see things very carefully, and at which we have the greatest acuity of vision; it is called the fovea or macula. The side parts of the eye, as we can immediately appreciate from our experience in looking at things, are not as effective for seeing detail as is the center of the eye. There is also a spot in the retina where the nerves carrying all the information run out; that is a blind spot. There is no sensitive part of the retina here, and it is possible to demonstrate that if we close, say, the left eye and look straight at something, and then move a finger or another small object slowly out of the field of view it suddenly disappears somewhere. The only practical use of this fact that we know of is that some physiologist became quite a favorite in the court of a king of France by pointing this out to him; in the boring sessions that he had with his courtiers, the king could amuse himself by “cutting off their heads” by looking at one and watching another’s head disappear.

Fig. 35–2. The structure of the retina. (Light enters from below.)

Figure 35–2 shows a magnified view of the inside of the retina in somewhat schematic form. In different parts of the retina there are different kinds of structures. The objects that occur more densely near the periphery of the retina are called rods. Closer to the fovea, we find, besides these rod cells, also cone cells. We shall describe the structure of these cells later. As we get close to the fovea, the number of cones increases, and in the fovea itself there are in fact nothing but cone cells, packed very tightly, so tightly that the cone cells are much finer, or narrower here than anywhere else. So we must appreciate that we see with the cones right in the middle of the field of view, but as we go to the periphery we have the other cells, the rods. Now the interesting thing is that in the retina each of the cells which is sensitive to light is not connected by a fiber directly to the optic nerve, but is connected to many other cells, which are themselves connected to each other. There are several kinds of cells: there are cells that carry the information toward the optic nerve, but there are others that are mainly interconnected “horizontally.” There are essentially four kinds of cells, but we shall not go into these details now. The main thing we emphasize is that the light signal is already being “thought about.” That is to say, the information from the various cells does not immediately go to the brain, spot for spot, but in the retina a certain amount of the information has already been digested, by a combining of the information from several visual receptors. It is important to understand that some brain-function phenomena occur in the eye itself.

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الحيوية

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الحيوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)