تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

The uncertainty principle

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 37

2024-04-20

1019

This is the way Heisenberg stated the uncertainty principle originally: If you make the measurement on any object, and you can determine the x-component of its momentum with an uncertainty Δp, you cannot, at the same time, know its x-position more accurately than Δx≥ℏ/2Δp. The uncertainties in the position and momentum at any instant must have their product greater than or equal to half the reduced Planck constant. This is a special case of the uncertainty principle that was stated above more generally. The more general statement was that one cannot design equipment in any way to determine which of two alternatives is taken, without, at the same time, destroying the pattern of interference.

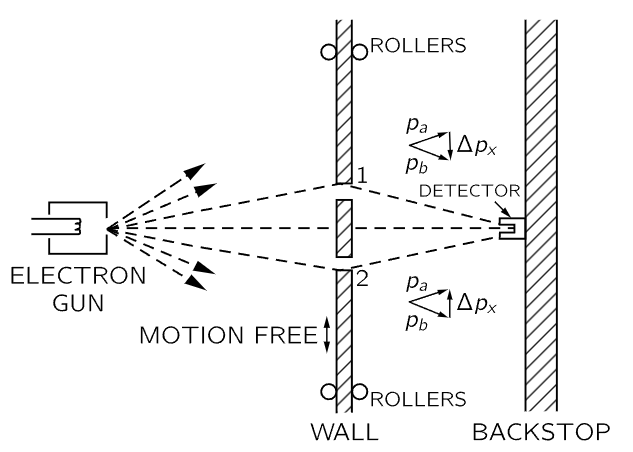

Let us show for one particular case that the kind of relation given by Heisenberg must be true in order to keep from getting into trouble. We imagine a modification of the experiment of Fig. 37–3, in which the wall with the holes consists of a plate mounted on rollers so that it can move freely up and down (in the x-direction), as shown in Fig. 37–6. By watching the motion of the plate carefully we can try to tell which hole an electron goes through. Imagine what happens when the detector is placed at x=0. We would expect that an electron which passes through hole 1 must be deflected downward by the plate to reach the detector. Since the vertical component of the electron momentum is changed, the plate must recoil with an equal momentum in the opposite direction. The plate will get an upward kick. If the electron goes through the lower hole, the plate should feel a downward kick. It is clear that for every position of the detector, the momentum received by the plate will have a different value for a traversal via hole 1 than for a traversal via hole 2. So! Without disturbing the electrons at all, but just by watching the plate, we can tell which path the electron used.

Fig. 37–6. An experiment in which the recoil of the wall is measured.

Now in order to do this it is necessary to know what the momentum of the screen is, before the electron goes through. So when we measure the momentum after the electron goes by, we can figure out how much the plate’s momentum has changed. But remember, according to the uncertainty principle we cannot at the same time know the position of the plate with an arbitrary accuracy. But if we do not know exactly where the plate is we cannot say precisely where the two holes are. They will be in a different place for every electron that goes through. This means that the center of our interference pattern will have a different location for each electron. The wiggles of the interference pattern will be smeared out. We shall show quantitatively in the next chapter that if we determine the momentum of the plate sufficiently accurately to determine from the recoil measurement which hole was used, then the uncertainty in the x-position of the plate will, according to the uncertainty principle, be enough to shift the pattern observed at the detector up and down in the x-direction about the distance from a maximum to its nearest minimum. Such a random shift is just enough to smear out the pattern so that no interference is observed.

The uncertainty principle “protects” quantum mechanics. Heisenberg recognized that if it were possible to measure the momentum and the position simultaneously with a greater accuracy, the quantum mechanics would collapse. So he proposed that it must be impossible. Then people sat down and tried to figure out ways of doing it, and nobody could figure out a way to measure the position and the momentum of anything—a screen, an electron, a billiard ball, anything—with any greater accuracy. Quantum mechanics maintains its perilous but accurate existence.