تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

The mean free path

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 43

2024-06-05

1813

Another way of describing the molecular collisions is to talk not about the time between collisions, but about how far the particle moves between collisions. If we say that the average time between collisions is τ, and that the molecules have a mean velocity v, we can expect that the average distance between collisions, which we shall call l, is just the product of τ and v. This distance between collisions is usually called the mean free path:

Mean free path l=τv. (43.9)

In this chapter we shall be a little careless about what kind of average we mean in any particular case. The various possible averages—the mean, the root-mean-square, etc.—are all nearly equal and differ by factors which are near to one. Since a detailed analysis is required to obtain the correct numerical factors anyway, we need not worry about which average is required at any particular point. We may also warn the reader that the algebraic symbols we are using for some of the physical quantities (e.g., l for the mean free path) do not follow a generally accepted convention, mainly because there is no general agreement.

Just as the chance that a molecule will have a collision in a short time dt is equal to dt/τ, the chance that it will have a collision in going a distance dx is dx/l. Following the same line of argument used above, the reader can show that the probability that a molecule will go at least the distance x before having its next collision is e−x/l.

The average distance a molecule goes before colliding with another molecule—the mean free path l—will depend on how many molecules there are around and on the “size” of the molecules, i.e., how big a target they represent. The effective “size” of a target in a collision we usually describe by a “collision cross section,” the same idea that is used in nuclear physics, or in light-scattering problems.

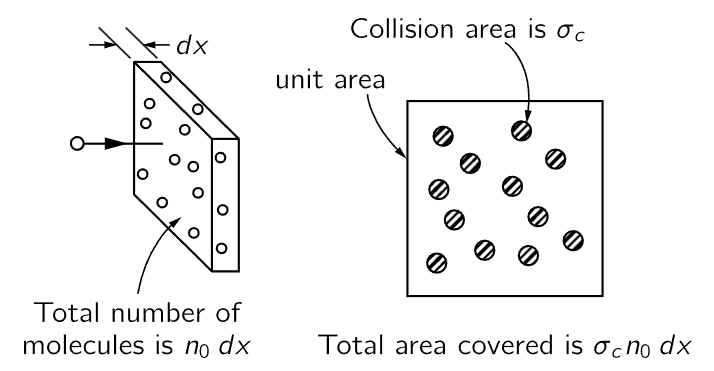

Fig. 43–1. Collision cross section.

Consider a moving particle which travels a distance dx through a gas which has n0 scatterers (molecules) per unit volume (Fig. 43–1). If we look at each unit of area perpendicular to the direction of motion of our selected particle, we will find there n0dx molecules. If each one presents an effective collision area or, as it is usually called, “collision cross section,” σc, then the total area covered by the scatterers is σcn0dx.

By “collision cross section” we mean the area within which the center of our particle must be located if it is to collide with a particular molecule. If molecules were little spheres (a classical picture) we would expect that σc=π(r1+r2)2, where r1 and r2 are the radii of the two colliding objects. The chance that our particle will have a collision is the ratio of the area covered by scattering molecules to the total area, which we have taken to be one. So the probability of a collision in going a distance dx is just σcn0dx:

Chance of a collision in dx = σcn0dx. (43.10)

We have seen above that the chance of a collision in dx can also be written in terms of the mean free path l as dx/l. Comparing this with (43.10), we can relate the mean free path to the collision cross section:

This formula can be thought of as saying that there should be one collision, on the average, when the particle goes through a distance l in which the scattering molecules could just cover the total area. In a cylindrical volume of length l and a base of unit area, there are n0l scatterers; if each one has an area σc the total area covered is n0lσc, which is just one unit of area. The whole area is not covered, of course, because some molecules are partly hidden behind others. That is why some molecules go farther than l before having a collision. It is only on the average that the molecules have a collision by the time they go the distance l. From measurements of the mean free path l we can determine the scattering cross section σc, and compare the result with calculations based on a detailed theory of atomic structure. But that is a different subject! So we return to the problem of nonequilibrium states.

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الجزيئية

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الجزيئية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)