Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Consonants Stops

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P107-C5

2025-03-08

5156

Consonants

Stops

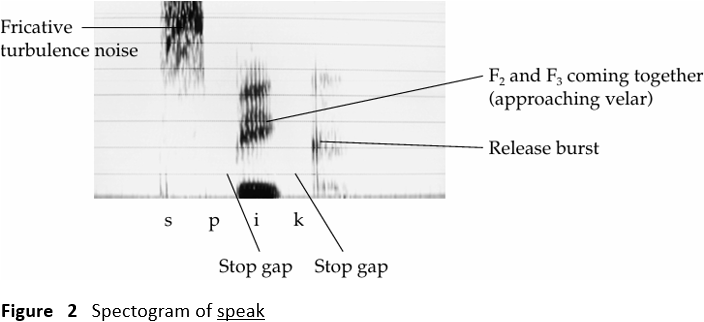

Stops are characterized on a spectrographic display by silence (stop gap) or obvious signal weakening. This is the acoustic interval corresponding to the articulatory occlusion, and it varies in duration depending on the prosodic condition. Because the vocal tract is obstructed, little or no energy is produced. This is followed by a burst of energy, as the closure is released.

There are two dimensions that need to be carefully analyzed in distinguishing stop sounds. One of them is the separation of fortis from lenis (or, as more commonly known, voiceless from voiced). Several indicators can help us to identify the stops with reference to this dimension. These are:

(a) Duration of the stop gap, i.e. the silent period during the closure phase. Specifically, /p, t, k/ show longer closure duration than /b, d, g/.

(b) Presence of a voice bar, i.e. a dark bar found at low frequencies (generally below 250 Hz) in a spectrogram. Except in intervocalic position, this is one of the least reliable identifying characteristics of the stop sounds. As we saw earlier, voicing is frequently absent in English /b, d, g/ in initial and final positions. Thus, this feature can reliably be used to separate /p, t, k/ from /b, d, g/ only in intervocalic positions; /b, d, g/ will show the voice bar that is indicative of voicing, whereas /p, t, k/ will not.

(c) Release burst indicated by a strong vertical spike. In general, we observe a stronger spike for /p, t, k/ than for /b, d, g/. One qualification is in order here for the final position: as discussed earlier, final stops in English are normally unreleased. In such cases, we will not observe any release burst. Velar stops are said to be more prone to non-release than bilabials or alveolars.

(d) Duration of the previous vowel. This refers to positions other than the initial position, where there is no vowel before the stop. In other positions, vowels and/or sonorant consonants are longer before /b, d, g/ than before /p, t, k/.

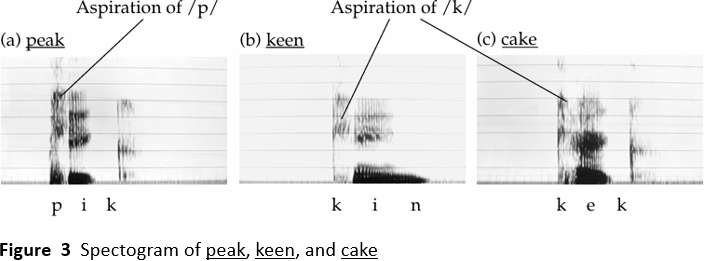

(e) Aspiration. A VOT of more than approximately 30 ms shows up as short frication noise (scattered marks after the release) before vowel formants begin, in initial /p, t, k/ of a stressed syllable.

The other dimension in the identification of stops is the place of articulation. While the above criteria are useful in separating voiced (lenis) from voiceless (fortis), we do not gather much information with respect to the place of articulation. In other words, what should we look for to distinguish a /p/ or a /b/ from a /t/ or a /d/, or from a /k/ or a /g/? The following are helpful in this respect:

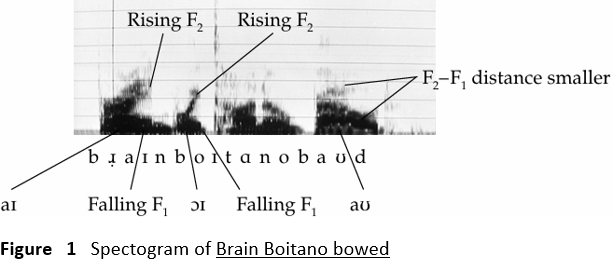

(a) Formant transitions. Formant transitions (shifts) in CV sequences reflect changes in vocal tract shaping during stop-to-vowel transition. Vowel to-stop (VC) transition is the opposite of the former. Frequency of the first formant of the vowel increases when stops are at the beginning of a syllable (CV), and falls when they are at the end (VC); this is the case for all stops. While no information for the place of articulation can be gathered from F1 transitions, F2 and F3 transitions can tell us a great deal in this respect. In CV situations, bilabials show upward movement of both F2 and F3 (more reliable before front vowels than before back vowels); the mirror image situation is revealed in a VC sequence. For a velar stop, F2 and F3 are close together just after the stop is formed (more reliable before back vowels; before front vowels, F3 and F4 have common origin). There will be a downward transition to a vowel with a high F2 . In cases of a VC, there is a narrowing (coming together) of the second and the third formants. The case of alveolar stops is probably the least straightforward; while we observe a flat transition to a vowel with mid or high F2 , there is a downward transition to a vowel with low F2 in CV cases. In VC cases, there is very little movement; small downward movement of the second formant and small upward movement of the third formant are expected.

(b) Locus (starting frequency). This is the point of origin to which the transition of the second formant appears to be pointing. F2 and F3 loci are described as an inherent property of the place of articulation for obstruents and nasals, although formant loci are not necessarily visible in the spectrogram. For a /b/, this is around 600–800 Hz; for a /d/, it is 1,800 Hz. To identify a /g/, two loci, at 3,000 Hz and 1,300 Hz, are generally noted.

(c) Release burst. Bilabials are identified by bursts with a center frequency lower than the F2 of the vowel (below 2,000 Hz). They show a pattern that is diffuse and weak. Alveolar bursts generally have a center frequency that is higher than the F2 of the vowel (above 2,000 Hz). The pattern is diffuse and strong. As for velars, they display a compact and strong pattern, and the bursts have a center frequency approximating to the F2 of the vowel.

(d) VOT (/p, t, k/ only). The length of time from the release of a stop until voicing begins for the following segment presents consistent differences depending on the place of articulation of the fortis stop. The time interval includes the spike (the sound that is produced by the separation of the articulators), a short frication noise after the spike, and the aspiration following it. As we move the place of articulation from the front to the back of the mouth, stops tend to have greater VOT. Although this is a rather effective acoustic property for classifying the place of articulation, it should be remembered that it is just a tendency, and that it may be possible to find an alveolar voiceless stop with a longer VOT than a velar voiceless stop. The VOT for a syllable-initial voiceless stop varies somewhat systematically depending on the place of articulation and other segmental context.

If we examine the spectrograms of the words speak, peak, keen, and cake (figures 2 and 3), we can see these points clearly. In speak, the /p/ is not at the beginning of a stressed syllable, since it is preceded by a /s/; thus we do not have aspiration in the voiceless bilabial stop. The words peak, keen, and cake all have voiceless stops at the beginning of a stressed syllable, and thus are aspirated. However, as one can easily see, the degree of the voice lag (aspiration) is different in each case; shorter in peak, longer in cake, and the longest in keen. The reasons for these differences are as follows. Among the three, peak has a bilabial stop whose expected lag is lower than that of the other two words that start with a velar stop. The difference between the two words that start with velar stops (cake and keen) is due to the type of vowel that follows the voiceless stop. The aspiration in keen is longer than in cake, because in the former /k/ is followed by a high vowel (a vowel with lower sonority), while in the latter the stop is followed by a lower vowel (a vowel with higher sonority).

Summarizing all the above, the examples confirm the statements made earlier: that voiceless stops are not aspirated if they are not at the beginning of a stressed syllable; when they are aspirated, the degree of aspiration is greater as we move the place of articulation from front to back (i.e. bilabial, to alveolar, and to velar). When a stop with a given place of articulation is followed by vowels of different height (different degrees of sonority), the amount of lag varies; a stop before a high vowel has greater aspiration than when it is before a low vowel. Flaps are different from their alveolar stop counterparts /t/ and /d/. In the production of stops, the vocal tract is blocked for about 50 ms, but in the flap, which is produced by a rapid throw of the tongue against the alveolar ridge, the duration is very short, about 20–30 ms; as such it is the fastest consonant.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)