Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The encyclopaedic view

المؤلف:

Vyvyan Evans and Melanie Green

المصدر:

Cognitive Linguistics an Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

C7-P215

2025-12-22

35

The encyclopaedic view

For the reasons outlined in the previous section, cognitive semanticists reject the ‘dictionary view’ of word meaning in favour of the ‘encyclopaedic view’. Before we proceed with our investigation of the encyclopaedic view, it is worth emphasising the point that, while the dictionary view represents a model of the knowledge of linguistic meaning, the encyclopaedic view represents a model of the system of conceptual knowledge that underlies linguistic meaning. It follows that this model takes into account a far broader range of phenomena than purely linguistic phenomena, in keeping with the ‘Cognitive Commitment’. This will become evident when we look at Fillmore’s theory of frames (section 7.2) and Langacker’s theory of domains (section 7.3). There are a number of characteristics associated with this model of the knowledge system, which we outline in this section:

1. There is no principled distinction between semantics and pragmatics.

2. Encyclopaedic knowledge is structured.

3. There is a distinction between encyclopaedic meaning and contextual meaning.

4. Lexical items are points of access to encyclopaedic knowledge.

5. Encyclopaedic knowledge is dynamic.

There is no principled distinction between semantics and pragmatics

Firstly, cognitive semanticists reject the idea that there is a principled dis tinction between ‘core’ meaning on the one hand, and pragmatic, social or cultural meaning on the other. This means that, among other things, cognitive semanticists do not make a sharp distinction between semantic and pragmatic knowledge. Knowledge of what words mean and knowledge about how words are used are both types of ‘semantic’ knowledge, according to this view. This is why cognitive semanticists study such a broad range of (linguistic and non-linguistic) phenomena in comparison to traditional or formal semanticists, and this also explains why there is no chapter in this book called ‘cognitive pragmatics’. This is not to say that the existence of pragmatic knowledge is denied. Instead, cognitive linguists claim that semantic and pragmatic knowledge cannot be clearly distinguished. As with the lexicon-grammar continuum, semantic and pragmatic knowledge can be thought of in terms of a continuum. While there may be qualitative distinctions at the extremes, it is often difficult in practice to draw a sharp distinction.

Cognitive semanticists do not posit an autonomous mental lexicon that contains semantic knowledge separately from other kinds of (linguistic or non linguistic) knowledge. It follows that there is no distinction between dictionary knowledge and encyclopaedic knowledge: there is only encyclopaedic knowledge, which subsumes what we might think of as dictionary knowledge.

The reason for adopting this position follows, in part, from the usage-based perspective developed in Chapter 4. The usage-based thesis holds, among other things, that context of use guides meaning construction. It follows from this position that word meaning is a consequence of language use, and that pragmatic meaning, rather than coded meaning, is ‘real’ meaning. Coded meaning, the stored mental representation of a lexical concept, is a schema: a skeletal representation of meaning abstracted from recurrent experience of language use. If meaning construction cannot be divorced from language use, then meaning is fundamentally pragmatic in nature because language in use is situated, and thus contextualised, by definition. As we have seen, this view is in direct opposition to the traditional view, which holds that definitional meaning is the proper subject of semantic investigation while pragmatic meaning relies upon non-linguistic knowledge.

Encyclopaedic knowledge is structured

The view that there is only encyclopaedic knowledge does not entail that the knowledge we have connected to any given word is a disorganised chaos. Cognitive semanticists view encyclopaedic knowledge as a structured system of knowledge, organised as a network, and not all aspects of the knowledge that is, in principle, accessible by a single word has equal standing. For example, what we know about the word banana includes information concerning its shape, colour, smell, texture and taste; whether we like or hate bananas; perhaps information about how and where bananas are grown and harvested; details relating to funny cartoons involving banana skins; and so on. However, certain aspects of this knowledge are more central than others to the meaning of banana.

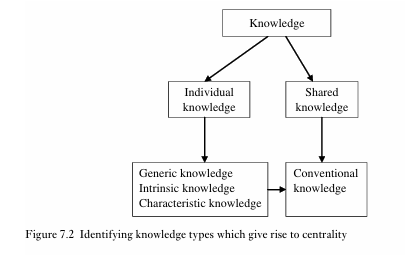

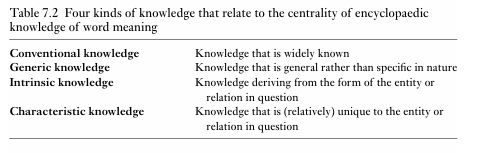

According to Langacker (1987), centrality relates to how salient certain aspects of the encyclopaedic knowledge associated with a word are to the meaning of that word. Langacker divides the types of knowledge that make up the encyclopaedic network into four types: (1) conventional; (2) generic; (3) intrinsic; and (4) characteristic. While these types of knowledge are in principle distinct, they frequently overlap, as we will show. Moreover, each of these kinds of knowledge can contribute to the relative salience of particular aspects of the meaning of a word.

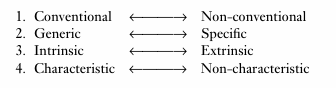

The conventional knowledge associated with a particular word concerns the extent to which a particular facet of knowledge is shared within a linguistic community. Generic knowledge concerns the degree of generality (as opposed to specificity) associated with a particular word. Intrinsic knowledge is that aspect of a word’s meaning that makes no reference to entities external to the referent. Finally, characteristic knowledge concerns aspects of the encyclopaedic information that are characteristic of or unique to the class of entities that the word designates. Each of these kinds of knowledge can be thought of as operating along a continuum: certain aspects of a word’s meaning are more or less conventional, or more or less generic, and so on, rather than having a fixed positive or negative value for these properties.

Conventional knowledge

Conventional knowledge is information that is widely known and shared between members of a speech community, and is thus likely to be more central to the mental representation of a particular lexical concept. The idea of conventional knowledge is not new in linguistics. Indeed, the early twentieth century linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1916), who we mentioned earlier in relation to the symbolic thesis, also observed that conventionality is an impor tant aspect of word meaning: given the arbitrary nature of the sound-meaning pairing (in other words, the fact that there is nothing intrinsically meaningful about individual speech sounds, and therefore nothing predictable about why a certain set of sounds and not others should convey a particular meaning), it is only because members of a speech community ‘agree’ that a certain word has a particular meaning that we can communicate successfully using language. Of course, in reality this ‘agreement’ is not a matter of choice but of learning, but it is this ‘agreement’ that represents conventionality in the linguistic sense.

For instance, conventional knowledge relating to the lexical concept BANANA might include the knowledge that some people in our culture have bananas with their lunch or that a banana can serve as a snack between meals. An example of non-conventional knowledge concerning a banana might be that the one you ate this morning gave you indigestion.

Generic knowledge

Generic knowledge applies to many instances of a particular category and therefore has a good chance of being conventional. Generic knowledge might include our knowledge that yellow bananas taste better than green bananas. This knowledge applies to bananas in general and is therefore generic. Generic knowledge contrasts with specific knowledge, which concerns individual instances of a category. For example, the knowledge that the banana you peeled this morning was unripe is specific knowledge, because it is specific to this particular banana. However, it is possible for large communities to share specific (non-generic) knowledge that has become conventional. For instance, generic knowledge relating to US presidents is that they serve a term of four years before either retiring or seeking re-election. This is generic knowledge, because it applies to US presidents in general. However, a few presidents have served shorter terms. For instance, John F. Kennedy served less than three years in office. This is specific knowledge, because it relates to one president in particular, yet it is widely known and therefore conventional. In the same way that specific knowledge can be conventional, generic knowledge can also be non conventional, even though these may not be the patterns we expect. For example, while scientists have uncovered the structure of the atom and know that all atoms share a certain structure (generic knowledge), the details of atomic structure are not widely known by the general population.

Intrinsic knowledge

Intrinsic knowledge relates to the internal properties of an entity that are not due to external influence. Shape is a good example of intrinsic knowledge relating to objects. For example, we know that bananas tend to have a characteristic curved shape. Because intrinsic knowledge is likely to be generic, it has a good chance of being conventional. However, not all intrinsic properties (for example, that bananas contain potassium) are readily identifiable and may not therefore be conventional. Intrinsic knowledge contrasts with extrinsic knowledge. Extrinsic knowledge relates to knowledge that is external to the entity: for example, the knowledge that still-life artists often paint bananas in bowls with other pieces of fruit relates to aspects of human culture and artistic convention rather than being intrinsic to bananas.

Characteristic knowledge

This relates to the degree to which knowledge is unique to a particular class of entities. For example, shape and colour may be more or less characteristic of an entity: the colour yellow is more characteristic of bananas than the colour red is characteristic of tomatoes, because fewer types of fruit are yellow than red (at least, in the average British supermarket). The fact that we can eat bananas is not characteristic, because we eat lots of other kinds of fruit.

The four types of knowledge we have discussed thus far relate to four continua, which are listed below. Knowledge can fall at any point on these continua, so that something can be known by only one person (wholly non-conventional) known by the entire discourse community (wholly conventional) or somewhere in between (for example, known by two people, a few people or many but not all people.

Of course, conventionality versus non-conventionality stands out in this classification of knowledge types because it relates to how widely something is known whereas the other knowledge types relate to the nature of the lexical concepts themselves. Thus it might seem that conventional knowledge is the most ‘important’ or ‘relevant’ kind when in fact it is only one ‘dimension’ of encyclopaedic knowledge. Figure 7.2 represents the interaction between the knowledge types discussed here. As this diagram illustrates, while generic, intrinsic and characteristic knowledge can be conventional (represented by the arrow going from the box containing these types of knowledge to the box containing conventional knowledge) they need not be. Conventional knowledge, on the other hand, is, by definition, knowledge that is shared.

Finally, let’s turn to the question of how these distinct knowledge types influence centrality. The centrality of a particular aspect of knowledge for a linguistic expression will always be dependent on the precise context in which the expression is embedded and on how well established the knowledge element is in memory. Moreover, the closer knowledge is to the left-hand side of the continua we listed above, the more salient that knowledge is and the more central that knowledge is to the meaning of a lexical concept. For example, for Joe Bloggs, the knowledge that bananas have a distinctive curved shape is conventional, generic, intrinsic and characteristic, and is therefore highly salient and therefore central to his knowledge about bananas and to the meaning of the lexical concept BANANA. The knowledge that Joe Bloggs has that he once peeled a banana and found a maggot inside is non-conventional, specific, extrinsic and non-characteristic, and hence is much less salient and less central to his knowledge about bananas. We summarise the four categories of encyclopaedic knowledge in Table 7.2.

There is a distinction between encyclopaedic meaning and contextual meaning

The third issue concerning the encyclopaedic view relates to the distinction between encyclopaedic meaning and contextual meaning (or situated meaning). Encyclopaedic meaning arises from the interaction of the four kinds of knowledge discussed above. However, encyclopaedic meaning arises in the context of use, so that the ‘selection’ of encyclopaedic meaning is informed by contextual factors. For example, recall our discussion of safe in Chapter 5. We saw that this word can have different meanings depending on the particular context of use: safe can mean ‘unlikely to cause harm’ when used in the context of a child playing with a spade, or safe can mean ‘unlikely to come to harm’ when used in the context of a beach that has been saved from development as a tourist resort. Similarly, the phenomenon of frame-dependent meaning briefly mentioned earlier suggests that the discourse context actually guides the nature of the encyclopaedic information that a lexical item prompts for. For instance, the kind of information evoked by use of the word foot will depend upon whether we are talking about rabbits, humans, tables or mountains. This phenomenon of contextual modulation (Cruse 1986) arises when a particular aspect of the encyclopaedic knowledge associated with a lexical item is privileged due to the discourse context.

Compared with the dictionary view of meaning, which separates core meaning (semantics) from non-core meaning (pragmatics), the encyclopaedic view makes very different claims. Not only does semantics include encyclopaedic knowledge, but meaning is fundamentally ‘guided’ by context. Furthermore, the meaning of a word is ‘constructed’ on line as a result of con textual information. From this perspective, fully-specified pre-assembled word meanings do not exist, but are selected and formed from encyclopaedic knowledge, which is called the meaning potential (Allwood 2003) or purport (Cruse 2000) of a lexical item. As a result of adopting the usage-based approach, then, cognitive linguists do not uphold a meaningful distinction between semantics and pragmatics, because word meaning is always a function of context (pragmatic meaning).

From this perspective, there are a number of different kinds of context that collectively serve to modulate any given instance of a lexical item as it occurs in a particular usage event. These types of context include (but are not necessarily limited to): (1) the encyclopaedic information accessed (the lexical concept’s context within a network of stored knowledge); (2) sentential context (the resulting sentence or utterance meaning); (3) prosodic context (the intonation pattern that accompanies the utterance, such as rising pitch to indicate a question); (4) situational context (the physical location in which the sentence is uttered); and (5) interpersonal context (the relationship holding at the time of utterance between the interlocutors). Each of these different kinds of context can contribute to the contextual modulation of a particular lexical item.

Lexical items are points of access to encyclopaedic knowledge

The encyclopaedic model views lexical items as points of access to encyclopaedic knowledge. According to this view, words are not containers that present neat pre-packaged bundles of information. Instead, they provide access to a vast network of encyclopaedic knowledge.

Encyclopaedic knowledge is dynamic

Finally, it is important to note that while the central meaning associated with a word is relatively stable, the encyclopaedic knowledge that each word provides access to, its encylopaedic network, is dynamic. Consider the lexical concept CAT. Our knowledge of cats continues to be modified as a result of our ongoing interaction with cats, our acquisition of knowledge regarding cats, and so on. For example, imagine that your cat comes home looking extremely unwell, suffering from muscle spasms and vomits a bright blue substance. After four days in and out of the animal hospital (and an extremely large vet’s bill) you will have acquired the knowledge that metaldehyde (the chemical used in slug pellets) is potentially fatal to cats. This information now forms part of your encyclopaedic knowledge prompted by the word cat, alongside the central knowledge that cats are small fluffy four-legged creatures with pointy ears and a tail.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)