علم الكيمياء

تاريخ الكيمياء والعلماء المشاهير

التحاضير والتجارب الكيميائية

المخاطر والوقاية في الكيمياء

اخرى

مقالات متنوعة في علم الكيمياء

كيمياء عامة

الكيمياء التحليلية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء التحليلية

التحليل النوعي والكمي

التحليل الآلي (الطيفي)

طرق الفصل والتنقية

الكيمياء الحياتية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الحياتية

الكاربوهيدرات

الاحماض الامينية والبروتينات

الانزيمات

الدهون

الاحماض النووية

الفيتامينات والمرافقات الانزيمية

الهرمونات

الكيمياء العضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الهايدروكاربونات

المركبات الوسطية وميكانيكيات التفاعلات العضوية

التشخيص العضوي

تجارب وتفاعلات في الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء الحرارية

حركية التفاعلات الكيميائية

الكيمياء الكهربائية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الجدول الدوري وخواص العناصر

نظريات التآصر الكيميائي

كيمياء العناصر الانتقالية ومركباتها المعقدة

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

كيمياء النانو

الكيمياء السريرية

الكيمياء الطبية والدوائية

كيمياء الاغذية والنواتج الطبيعية

الكيمياء الجنائية

الكيمياء الصناعية

البترو كيمياويات

الكيمياء الخضراء

كيمياء البيئة

كيمياء البوليمرات

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الصناعية

الكيمياء الاشعاعية والنووية

The spin quantum number and the magnetic spin quantum number

المؤلف:

CATHERINE E. HOUSECROFT AND ALAN G. SHARPE

المصدر:

INORGANIC CHEMISTRY

الجزء والصفحة:

p15

31-12-2015

3657

The spin quantum number and the magnetic spin quantum number

Before we place electrons into atomic orbitals, we must define two more quantum numbers. In a classical model, an electron is considered to spin about an axis passing through it and to have spin angular momentum in additionto orbital angular momentum . The spin quantum number, s, determines the magnitude of the spin angular momentum of an electron and has a value of 1/2. Since angularmomentum is a vector quantity, it must have direction, and this is determined by the magnetic spin quantum number, ms, which has a value of 1/2 or -1/2. Whereas an atomic orbital is defined by a unique set of three quantum numbers, an electron in an atomic orbital is defined by a unique set of four quantum numbers: n, Ɩ, m Ɩ and ms. As there are only two values of ms, an orbital can accommodate only two electrons. An orbital is fully occupied when it contains two electrons which are spin-paired; one electron has a value of ms = 1/2 and the other, ms =-1/2.

Box 1.5 Angular momentum, the inner quantum number, j, and spin–orbit coupling

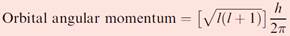

The value of l determines not only the shape of an orbital butalso the amount of orbital angular momentum associated with an electron in it:

The axis through the nucleus about which the electron (considered classically) can be thought to rotate defines the direction of the orbital angular momentum. The latter gives rise to a magnetic moment whose direction is in the same sense as the angular vector and whose magnitude is proportional to the magnitude of the vector. An electron in an s orbital (l = 0) has no orbital angular momentum, an electron in a p orbital (Ɩ = 1) has angular momentum √2 (h/2π ) and so on. The orbital angular momentum vector has (2 Ɩ + 1) possible directions in space corresponding to the (2 Ɩ+ 1) possible values of ml for a given value of Ɩ. We are particularly interested in the component of the angular momentum vector along the z axis; this has a different value for each of the possible orientations that this vector can take up. The actual magnitude of the z component is given by mƖ (h / 2π ).

Thus, for an electron in a d orbital (Ɩ = 2), the orbital angular momentum is √6 (h/2π ), and the z component of this may have values of +2(h/2π ), +(h/2π ), 0, - (h/2π ), or - 2(h/2π ) . The orbitals in a sub-shell of given n and Ɩ , are, as we have seen, degenerate. If, however, the atom is placed in a magnetic field, this degeneracy is removed. And, if we arbitrarily define the direction of the magnetic field as the z axis, electrons in the various d orbitals will interact to different extents with the magnetic field as a consequence of their different values of the z components of their angular momentum vectors (and, hence, orbital magnetic moment vectors).

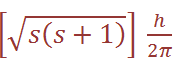

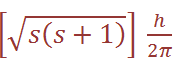

An electron also has spin angular momentum which can be regarded as originating in the rotation of the electron about its own axis. The magnitude of this is given by: Spin angular momentum=  where s = spin quantum number. The axis defines the direction of the spin angular momentum vector, but again it is the orientation of this vector with respect to the z direction in which we are particularly interested. The z component is given by

where s = spin quantum number. The axis defines the direction of the spin angular momentum vector, but again it is the orientation of this vector with respect to the z direction in which we are particularly interested. The z component is given by (since ms can only equal +1/2 or – 1/2 , there are just two possible orientations of the spin angular momentum vector, and these give rise to z components of magnitude +1/2 (h/2π ), - 1/2 (h/2π ). For an electron having both orbital and spin angular momentum, the total angular momentum vector is given by: Total angular momentum =

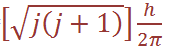

(since ms can only equal +1/2 or – 1/2 , there are just two possible orientations of the spin angular momentum vector, and these give rise to z components of magnitude +1/2 (h/2π ), - 1/2 (h/2π ). For an electron having both orbital and spin angular momentum, the total angular momentum vector is given by: Total angular momentum =  where j is the so-called inner quantum number; j may have values of (Ɩ + s) or (Ɩ – s), i.e. Ɩ +1/2 or Ɩ –1/2. (When Ɩ = 0 and the electron has no orbital angular momentum, the total angular momentum is

where j is the so-called inner quantum number; j may have values of (Ɩ + s) or (Ɩ – s), i.e. Ɩ +1/2 or Ɩ –1/2. (When Ɩ = 0 and the electron has no orbital angular momentum, the total angular momentum is  because j = s.) The z component of the total angular momentum vector is now j (h/2π ) and there are (2j + 1)possible orientations in space. For an electron in an ns orbital (Ɩ = 0 (, j can only be1/2. When the electron is promoted to an np orbital, j may be 3/2 or 1/2 , and the energies corresponding to the different j values are not quite equal. In the emission spectrum of sodium, for example, transitions from the 3p3/2 and 3p1/2 levels to the 3s1/2 level therefore correspond to slightly different amounts of energy, and this spin–orbit coupling is the origin of the doublet structure of the strong yellow line in the spectrum of atomic sodium. The fine structure of many other spectral lines arises in analogous ways, though the number actually observed depends on the difference in energy between states differing only in j value and on the resolving power of the spectrometer. The difference in energy between levels for which Δ j = 1 (the spin–orbit coupling constant, λ) increases with the atomic number of the element involved; e.g. that between the np3/2 and np1/2 levels for Li, Na and Cs is 0.23, 11.4 and 370 cm-1 respectively.

because j = s.) The z component of the total angular momentum vector is now j (h/2π ) and there are (2j + 1)possible orientations in space. For an electron in an ns orbital (Ɩ = 0 (, j can only be1/2. When the electron is promoted to an np orbital, j may be 3/2 or 1/2 , and the energies corresponding to the different j values are not quite equal. In the emission spectrum of sodium, for example, transitions from the 3p3/2 and 3p1/2 levels to the 3s1/2 level therefore correspond to slightly different amounts of energy, and this spin–orbit coupling is the origin of the doublet structure of the strong yellow line in the spectrum of atomic sodium. The fine structure of many other spectral lines arises in analogous ways, though the number actually observed depends on the difference in energy between states differing only in j value and on the resolving power of the spectrometer. The difference in energy between levels for which Δ j = 1 (the spin–orbit coupling constant, λ) increases with the atomic number of the element involved; e.g. that between the np3/2 and np1/2 levels for Li, Na and Cs is 0.23, 11.4 and 370 cm-1 respectively.

Worked example / Quantum numbers:

An electron in an atomic orbital Write down two possible sets of quantum numbers that describe an electron in a 2s atomic orbital. What is the physical significance of these unique sets?

The 2s atomic orbital is defined by the set of quantum numbers n = 2, Ɩ = 0, mƖ = 0.An electron in a 2s atomic orbital may have one of two sets of four quantum numbers:

n = 2, Ɩ = 0, mƖ = 0, ms = + 1/2 or n = 2, Ɩ = 0, mƖ = 0, ms = - 1/2 If the orbital were fully occupied with two electrons, one electron would have ms = + 1/2

, and the other electron would have ms = - 1/2 , i.e. the two electrons would be spin paired.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء اللاعضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)