النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Brucella, Bordetella and Francisella

المؤلف:

Fritz H. Kayser

المصدر:

Medical Microbiology -2005

الجزء والصفحة:

7-3-2016

3047

Brucella, Bordetella and Francisella

The genera Brucella, Bordetella, and Francisella are small, coccoid, Gram- negative rods. They can be cultured under strict aerobic conditions on enriched nutrient mediums.

Brucella abortus, B. melitensis, and B. suis cause brucellosis, a classic zoonosis that affects cattle, goats, and pigs. The pathogens can be transmitted to humans directly from diseased animals or indirectly in food. They cause characteristic granulomas in the organs of the RES. The primary clinical symptom is the undulant fever. Diagnosis is by means of pathogen identification or antibody assay using a standardized agglutination reaction.

Bordetella pertussis is the causative organism of whooping cough, which affects only humans. The pathogens are transmitted by aerosol droplets. The organism is not characterized by specific invasive properties, although it is able to cause epithelial and subepithelial necroses in the mucosa of the lower respiratory tract. The catarrhal phase, paroxysmal phase, and convalescent phase characterize the clinical picture of whooping cough (pertussis), which is usually diagnosed clinically. During the catarrhal and early paroxysmal phases, the pathogens can be cultured from nasopharyngeal secretions. The most important prophylactic measure is the vaccination in the first year of life.

Francisella tularensis causes tularemia. This disease, rare in Europe, affects wild rodents and can be transmitted to humans by direct contact, by arthropod vectors, and by dust particles.

Brucella (Brucellosis, Bang’s Disease)

Occurrence and classification. The genus Brucella includes three medically relevant species B. abortus, B. melitensis, and B. suis besides a number of others. These three species are the causative organisms of classic zoonoses in livestock and wild animals, specifically in cattle (B. abortus), goats (B. melitensis), and pigs (B. suis). These bacteria can also be transmitted from diseased animals to humans, causing a uniform clinical picture, so-called undulant fever or Bang's disease.

Morphology and culture. Brucellae are slight, coccoid, Gram-negative rods with no flagella. They only reproduce aerobically. In the initial isolation the atmosphere must contain 5-10% CO2. Enriched mediums such as blood agar are required to grow them in cultures.

Pathogenesis and clinical picture. Human brucellosis infections result from direct contact with diseased animals or indirectly by way of contaminated foods, in particular unpasteurized milk and dairy products. The bacteria invade the body either through the mucosa of the upper intestinal and respiratory tracts or through lesions in the skin, then enter the subserosa or subcutis. From there they are transported by microphages or macrophages, in which they can survive, to the lymph nodes, where a lymphadenitis develops. The pathogens then disseminate from the affected lymph nodes, at first lymphogenously and then hematogenously, finally reaching the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and other RES tissues, in the cells of which they can survive and even multiply. The granulomas typical of intracellular bacteria develop. From these inflammatory foci, the brucellae can enter the bloodstream intermittently, each time causing one of the typical febrile episodes, which usually occur in the evening and are accompanied by chills. The incubation period is one to four weeks. B. melitensis infections are characterized by more severe clinical symptoms than the other brucelloses.

Diagnosis. This is best achieved by isolating the pathogen from blood or biopsies in cultures, which must be incubated for up to four weeks. The laboratory must therefore be informed of the tentative diagnosis. Brucellae are identified based on various metabolic properties and the presence of surface antigens, which are detected using a polyvalent Brucella-antiserum in a slide agglutination reaction. Special laboratories are also equipped to differentiate the three Brucella species.

Antibody detection is done using the agglutination reaction according to Gruber-Widal in a standardized method. In doubtful cases, the complement- binding reaction and direct Coombs test can be applied to obtain a serological diagnosis.

Therapy. Doxycycline is administered in the acute phase, often in combination with gentamicin. A therapeutic alternative is cotrimoxazole. The antibiotic regimen must be continued for three to four weeks.

Epidemiology and prevention. Brucellosis is a zoonosis that affects animals all over the world. Infections with B. melitensis occur most frequently in Mediterranean countries, in Latin America, and in Asia. The melitensis brucelloses seen in Europe are either caused by milk products imported from these countries or occur in travelers. B. abortus infections used to be frequent in central Europe, but the disease has now practically disappeared there thanks to the elimination of Brucella-infested cattle herds. Although control of brucellosis infections focuses on prevention of exposure to the pathogen, it is not necessary to isolate infected persons since the infection is not communicable between humans. There is no vaccine.

Bordetella (Whooping Cough, Pertussis)

The genus Bordetella, among others, includes the species B. pertussis, B. para-pertussis, and B. bronchiseptica. Of the three, the pathogen responsible for whooping cough, B. pertussis, is of greatest concern for humans. The other two species are occasionally observed as human pathogens in lower respiratory tract infections.

Morphology and culture. B. pertussis bacteria are small, coccoid, nonmotile, Gram-negative rods that can be grown aerobically on special culture mediums at 37 °C for three to four days.

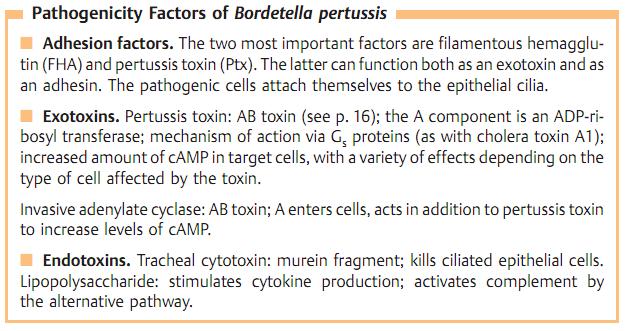

Pathogenesis. Pertussis bacteria are transmitted by aerosol droplets. They are able to attach themselves to the cells of the ciliated epithelium in the bronchi. They rarely invade the epithelium. The infection results in (sub-) epithelial inflammations and necroses.

Clinical picture. The onset of whooping cough (pertussis) develops after an incubation period of about 10-14 days with an uncharacteristic catarrhal phase lasting 1-2 weeks, followed by the two to three week-long paroxysmal phase with typical convulsive coughing spells. Then comes the convalescent phase, which can last for several weeks. Frequent complications, especially in infants, include secondary pneumonias caused by pneumococci or Haemophilus, which are able to penetrate readily through the damaged mucosa, and otitis media. Encephalopathy develops as a delayed complication in a small number of cases (0.4%), whereby the pathomechanism has not yet been clarified. The lethality level for pertussis during the first year of life is approximately 1-2%. The infection confers a stable immunity. Adults who were vaccinated as children have little or no residual immunity and often present atypical pertussis.

Diagnosis. The pathogen can only be isolated and identified during the catarrhal and early paroxysmal phases. Specimen material is taken from the nasopharynx through the nose using a special swabbing technique. A special medium is then carefully inoculated or the specimen is transported to the laboratory using a suitable transport medium. B. pertussis can also be identified in nasopharyngeal secretion using the direct immunofluorescence technique. Cultures must be aerobically incubated for three to four days. Antibodies cannot be detected by EIA until two weeks after onset at the earliest. Only a seroconversion is conclusive.

Therapy. Antibiotic treatment can only be expected to be effective during the catarrhal and early paroxysmal phases before the virulence factors are bound to the corresponding cell receptors. Macrolides are the agents of choice.

Epidemiology and prevention. Pertussis occurs worldwide. Humans are the only hosts. Sources of infection are infected persons during the catarrhal phase, who cough out the pathogens in droplets. There are no healthy carriers. The most important preventive measure is the active vaccination (see vaccination schedule, p. 33). Although a whole-cell vaccine is available, various acellular vaccines are now preferred.

Francisella tularensis (Tularemia)

F. tularensis bacteria are coccoid, non-motile, Gram-negative, aerobic rods. They cause a disease similar to plague in numerous animal species, above all in rodents. Humans are infected by contact with diseased animals or ectoparasites or dust. The pathogens invade the host either through microtraumata in the skin or through the mucosa. An ulcerous lesion develops at the portal of entry that also affects the local lymph nodes (ulcero-glandular, glandular, or oculo-glandular form). Via lymphogenous and hematogenous dissemination the pathogens then spread to parenchymatous organs, in particular RES organs such as the spleen and liver. Small granulomas develop, which develop central caseation or purulent abscesses. In pneumonic tularemia, as few as 50 CFU cause disease. The incubation period is three to four days. Diagnostic procedures aim to isolate and identify the pathogen in cultures and under the microscope. Agglutinating antibodies can be detected beginning with the second week. A seroconversion is the confirming factor. Antibiosis is carried out with streptomycin or gentamicin.

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)