تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

WAVE PROPERTIES OF PARTICLES (DUALITY)

المؤلف:

Mark Csele

المصدر:

FUNDAMENTALS OF LIGHT SOURCES AND LASERS

الجزء والصفحة:

p50

9-3-2016

1738

WAVE PROPERTIES OF PARTICLES (DUALITY)

Although classical physicists had thought of electromagnetic radiation as a wave for many years, experimental evidence provided by the photoelectric effect had shown that depending on the circumstances, it could exhibit particle qualities. The converse is also true: A particle can exhibit wave behavior. In 1924, Louis deBroglie attempted to calculate the wavelength associated with a particle. By combining the Planck Einstein relation for photons, E = hv (stating that the energy of the photon was related to the frequency or wavelength), with Einstein’s famous statement of mass to energy equivalency, E = mc2, he speculated that wave behavior was a property of all moving objects and developed a mathematical relationship allowing determination of wavelength. At face value this seems absurd, but under the right circumstances wave behavior is indeed observed, as we shall see in the next section, where an electron, clearly a particle, exhibits wave behavior under the right circumstances. Central to deBroglie’s hypothesis was that any particle with momentum has an associated wavelength. This relation is easily derived from the Einstein Planck equation combined with the relation for an electromagnetic wave, namely E = cp, where c is the speed of light and p is the momentum, as follows:

E = hv = cp yielding hv = cp (1.1)

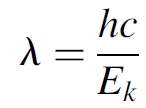

Substituting for n = c/λ, we now get λ = h/p. Relation (1.1) holds true for low energy particles, where the momentum can be found using a simple relation from kinematics: namely,

p = (2mEk)1/2 (1.2)

where Ek is the kinetic energy of the particle and m is the mass. Because of relativity, a glitch occurs when considering high-energy particles. As a particle acquires more energy, it approaches the speed of light. As this happens, the apparent mass of these particles changes and must be accounted for. Factoring in relativity, the deBroglie wavelength for a high-energy particle is simply

(1.3)

(1.3)

where Ek is the kinetic energy of the particle. The greater the mass and velocity of a particle, the shorter its wavelength. For ordinary macroscopic particles, the wavelength is so short that it can never be measured, but for small subatomic particles with little mass, the wavelengths are well within observable ranges.

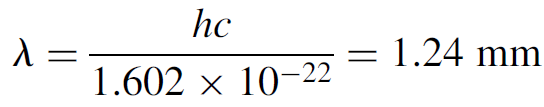

Example 1.1 Wavelength Measurement Consider the wavelength of an electron with energy 0.001 eV (or 1.602 ×10-22 J):

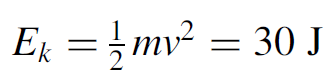

This is in the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum and is easily measured. Now consider the wavelength of an electron with energy 2.0 eV (or 3.204 × 10-19 J). The wavelength is found to be 620 nm, which is in the visible spectrum (red) and is easily measured using a spectroscope. Similarly, an electron with energy 10 keV has a wavelength of 1.24 × 10-10 m. This is in the x-ray region of the electromagnetic spectrum. With wavelengths this short it is not possible to use a diffraction grating (as we use for visible light) since the spacing between the lines needs be so close that such a grating cannot be manufactured. A simple solution is to use a crystal as a diffraction grating. The spacing of atoms in the crystal is just right to allow diffraction to occur when x-rays are beamed at the crystal. In this manner an x-ray spectrometer can be built which works in the same manner as an optical spectroscope, where by measuring the angle of diffraction, the wavelength of the incident radiation may be determined. Finally, consider a macroscopic object such as a 150-g ball hurled at 20 m/s. The kinetic energy of the ball is

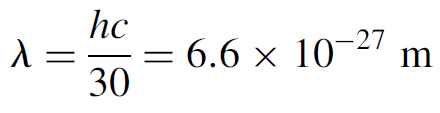

so the wavelength is

This wavelength is far too short to measure it is well beyond cosmic rays (the shortest wavelength radiation known). This illustrates why normal everyday (i.e., macroscopic) objects do not exhibit wave behavior (or at least observable wave behavior).

الاكثر قراءة في ميكانيكا الكم

الاكثر قراءة في ميكانيكا الكم

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)