النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Introduction to Transport Processes in Plants

المؤلف:

AN INTRODUCTION TO PLANT BIOLOGY-1998

المصدر:

JAMES D. MAUSETH

الجزء والصفحة:

1-11-2016

2832

Introduction to Transport Processes in Plants

one fundamental aspect of life itself is the ability to transport specific substances to particular sites, moving molecules against the direction in which they would diffuse if left alone. After death occurs, atoms, ions, and molecules diffuse, moving from regions of higher to lower concentration, and the organization of protoplasm decays; the disorder of the components increases. Diffusion also occurs during life but proceeds more slowly than the controlled and oriented transport processes that tend to increase the order within the plant or animal body. Transport processes consume energy, and many are driven by the exergonic breaking of ATP's high-energy phosphate-bonding orbitals.

Specific transport occurs at virtually every level of biological organization: Enzymes transport electrons, protons, and acetyl groups; membranes transport material across themselves; cells transport material into and out of themselves as well as circulate it within the protoplasm; whole organisms transport water, carbohydrates, minerals, and other nutrients from one organ to another—between roots, leaves, flowers, and fruits.

Plants have only a few basic types of transport processes, and the fundamental principles are easy to understand. They are grouped here into short distance transport, which involves distances of a few cell diameters or less, and long distance transport between cells that are not close neighbors.

Many types of short distance transport involve transfer of basic nutrients from cells with access to the nutrients to cells that need them but are not in direct contact with them. Such transport requirements arose when early organisms evolved such that they had interior cells that were not in contact with the environment. Short distance transport became necessary to the survival of internal cells.

Long distance transport is not absolutely essential in the construction of a large plant. Many large algae have no long distance transport, nor do sponges, corals, or similar animals. However, the ability to conduct over long distances is definitely adaptive, especially for land plants. Before xylem and phloem evolved, a plant's absorbing cells could ret penetrate deep into soil, because they would starve so far from photosynthetic cells. Nor could they have transported their absorbed nutrients very far upward. Being limited to the uppermost millimeter or two of soil meant that the absorptive cells could not reach the more permanently moist, deep soil where there are more minerals; the uppermost layers dry quickly and free minerals are leached away by rain. With xylem and phloem, roots that penetrate deeply can be kept alive and their gathered nutrients can be carried up to the shoot.

Vascular tissues make it selectively advantageous for shoots to grow upright, elevating leaves into the sunlight above competing plants. This elevation is feasible because photo- synthetically produced sugars can be transported downward to other plant parts. Such elevation of photosynthetic tissues resulted in tall plants that could also place their reproductive tissues at a high elevation, enabling spores or pollen to be distributed more widely and effectively by the wind. After insect-mediated pollination evolved, it was adaptive to have flowers located high, in an easily visible position. The evolution of transport processes affected all aspects of plant biology and permitted later evolution of many new types of plant organization.

Vascular tissues also act as a mechanism by which nutrients are channeled to specific sites, resulting in rapid growth and development of those sites (Fig.1). If meristematic zones relied exclusively on their own photosynthesis, growth and leaf primordium initiation would be extremely slow. At other times of the year, nutrients can be directed to flower buds or young fruits, promoting their growth while inhibiting the formation of new leaves.

FIGURE 1: (a) Imagine an angiosperm that has no vascular tissue. The leaves would produce large amounts of glucose, far in excess of the metabolic needs of the tissue itself. But because diffusion is slow over long distances, the sugar would diffuse out of the leaf only slowly and in small quantities. The shoot apex has almost no chlorophyll; if it had to depend solely on its own photosynthesis, growth, leaf initiation, and leaf expansion would be extremely slow, even though they would be occurring only a few centimeters away from large quantities of glucose in leaves. (b) With vasculature, glucose can be transported from regions of excess to regions of need; apical meristems and leaf primordia can thereby grow very rapidly. Vascular tissues also make the minerals gathered by an extensive root system available to regions that need them.

The combination of short and long distance transport has resulted in the ability of some plants to become large and complex enough to survive temporary adverse conditions, such as drought, heat, or attack by pathogens.

Because almost everything transported by a plant is dissolved in water, the ability of water to move from cell to cell or throughout a plant is an important factor. Water is an unusual liquid: It is rather heavy and viscous, and it tends to adhere to cell components as well as to soil, factors that affect transport processes.

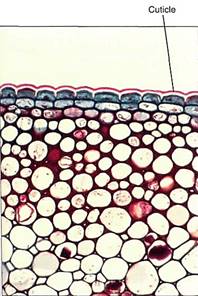

Related to transport processes are isolation mechanisms that inhibit the movement of substances. Plants are adept at synthesizing organic polymers impermeable to a variety of substances. The epidermis with its cutin-lined walls is an excellent means of keeping water in the shoot after it has been transported there by the xylem (Fig. 2). The Casparian strips of the endodermis prevent the diffusion of minerals from one part of a root to another. Isolation mechanisms are essential if transport is to be useful.

FIGURE 2:The cuticle (pink), composed of cutin, is a waterproof epidermal layer that acts as an isolation mechanism, retaining water within the plant and keeping pathogens out (X 80).

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)