النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Introducion to Structure of Woody Plants

المؤلف:

AN INTRODUCTION TO PLANT BIOLOGY-1998

المصدر:

JAMES D. MAUSETH

الجزء والصفحة:

8-11-2016

2803

Introducion to Structure of Woody Plants

In previous chapters, growth by means of apical meristems was described. From the meristems are derived sets of tissues: epidermis, cortex, vascular bundles, pith, and leaves. These primary tissues together constitute the primary plant body. In plants known technically as herbs, this is the only body that ever develops, but in woody species, additional tissues are produced in the stem and root from other meristems—the vascular cambium and the cork cambium. The new tissues themselves are the wood (secondary xylem) and the bark (secondary phloem and cork); they are secondary tissues, and they constitute the plant's secondary body. Examples of woody plants are abundant: Trees such as sycamores, chestnuts, pines, and firs are woody, as are shrubs like roses, oleanders, and azaleas.

The ability to undergo secondary growth and produce a woody body has many important consequences. In an herb, once a portion of stem or root is mature, its conducting capacity is set: All provascular cells have differentiated into either primary xylem or primary phloem. This capacity is correlated with the needs of leaves and roots. If the plant produces so many leaves that they lose water faster than the stem xylem can conduct, some or all of the leaves die of water loss. Similarly, it would not be selectively advantageous for produces only as many leaves as it had during the first year. In other species, adventitious roots are produced which supply conduction capacity directly to the new section of stem being formed, thus bypassing the older portions of the stem . Most of these plants must remain low enough for adventitious roots to reach the soil, so these are often rhizomatous, such as irises, bamboo, and ferns.

Woody plants not only become taller through growth by their apical meristems but also become wider by the accumulation of wood and bark. Because wood and bark contain conducting tissues, their accumulation gives plants a greater capacity to move water and minerals upward and carbohydrates downward. The number of leaves and roots that the plant can support increases, as does the photosynthetic capacity.

For example, consider a tree with a trunk radius of 10.5 cm (Fig.1); imagine that the plant produced a layer of wood 0.5 cm thick in the previous year. As a consequence, the tree has 32.2 cm2 of new wood that conducts water from roots to leaves. Assume that each leaf loses water at a rate equal to the conduction capacity of 0.1 cm2 of wood; this plant can conduct enough water through its trunk to support 323 leaves. If the tree produces another 0.5 cm of wood this year, the new ring of wood will have a cross-sectional area of 33.8 cm2. It is larger than the previous ring of wood and can support conduction to a greater number of leaves-338. Even if a ring of wood could conduct for only 1 year, the plant could still produce a greater number of leaves every year, so its annual photosynthetic capacity would always increase. The consequence of this ever-increasing capacity is that annual production of seeds and defensive chemicals also increases.

FIGURE 1: The cross-sectional area of a ring of wood is given by the formula P times the square of the outer radius minus the square of the inner radius. If each annual ring is 0.5 cm wide, when the wood has a radius of 10.5 cm, its newest ring has a cross-sectional area of 32.2 cm2. Next year's ring will be larger, 33.8 cm2, an increase of (33.8 - 32.2)/32.2 = 1.6/32.2 X 100% = 5% (notice that this is not drawn to scale).

Only those seeds that germinate in a suitable site are able to grow into adults and reproduce. Once a seed of a woody, perennial plant germinates and becomes established, it occupies its favorable site year after year. Other seeds may not be able to germinate because they do not encounter suitable sites. In the springtime, all the sites that had been occupied by herbs are vacant and available to the seeds of both annual herbs and woody perennials, but virtually all the sites occupied by last year's perennials are still occupied by them. Many pines, oaks, and other long-lived trees hold on to the same piece of Earth for as long as 600 years and a few for up to 3000 years; one particular tree has lived for 5000 years. For all that time the trees produce seeds of their own and, by their very presence, prevent the seeds of their competitors from growing at that site. Annual herbs give up their sites when they die; their seeds must compete l or new sites every year.

Secondary growth also has disadvantages: A 5000-year-old plant is 10,000 times older than an herb that germinates in April, lives 6 months, then sets seed and dies by September.

It has had to battle insects, fungi, and environmental harshness 10,000 times longer, and it is a bigger, more easily discovered target for pathogens. Perennials have a greater need fir defenses, both chemical and structural, than annual herbs have, and they must use a portion of their energy and nutrient resources for winterizing their bodies if they live in temperate climates. It is also expensive metabolically to construct wood and bark. The fict that wood burns so readily shows that it is energy-rich. If no secondary growth occurred, this energy could be used immediately for reproduction. In fact, most woody plants do not reproduce until they are several years old; if they are killed by disease or environmental stress before they reproduce, all growth and development have been for nothing.

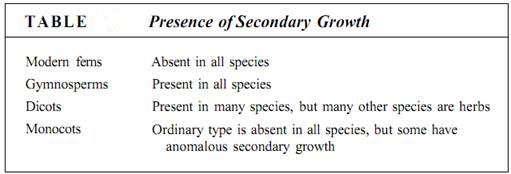

It must be difficult for secondary growth to arise by evolution; it has evolved only three times in the 420 million years that vascular plants have been in existence, and two of those evolutionary lines later became extinct . All woody trees and shrubs alive today have descended from just one group of primitive woody plants that arose about 370 million years ago. This group has been very successful, evolving into many species and dominating almost all regions of Earth; they include all gymnosperms and many angiosperms. Within the flowering plants, herbaceousness is a new phenomenon; all early angiosperms were woody perennials, but many plants have evolved to be herbs, foregoing the woody life style. At present, true secondary growth occurs in all gymnosperms and many dicots, but not in any ferns or monocots (Table ).

As you study this, remember that a woody plant is a combination of primary and secondary tissues: The tips of the stems and roots, as well as the leaves, flowers, and fruits, are herbaceous and primary; only as portions of stems and roots become older do they begin to undergo secondary growth and become woody.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)