تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Megalithic man and the Sun

المؤلف:

A. Roy, D. Clarke

المصدر:

Astronomy - Principles and Practice 4th ed

الجزء والصفحة:

p 76

26-7-2020

2905

Megalithic man and the Sun

The Sun, as god and giver of light, warmth and harvest, was all-important. He was a Being to be worshipped and placated by ritual and sacrifice. On a more practical note, his movements provided a calendar by which ritual and seed time and harvest could be regulated. Throughout the United Kingdom, for example, between the middles of the third and second millennia BC, vast numbers of solar observatories were built. Some were simple, consisting of a single alignment of stones; others were much more complicated, involving multiple stone circles with outlying stones making ingenious use of natural foresites along the horizon to increase their observational accuracy. A surprising number of suchmegalithic sites still exist, the most famous of which are Stonehenge, in England, and Callanish, in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland.

One example will be sufficient to illustrate megalithic man’s ingenuity. It exists at Ballochroy on the west coast of the Mull of Kintyre, Scotland.

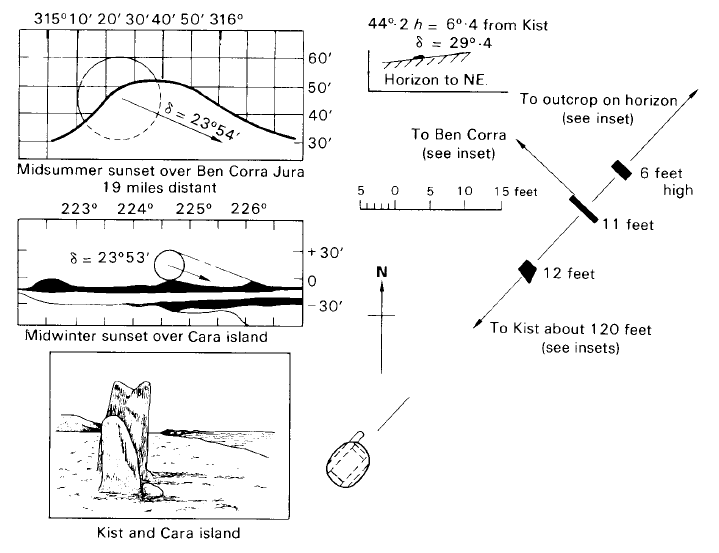

Figure 1. Megalithic man’s sighting stones at Ballochroy (55◦ 42' 44'' N, 5◦ 36' 45'' W).

Three large stones (see figure 1) are set up in line close together; a stone kist (a grave built of stone slabs) is found on this line to the south-west, about 40 m from the stones. The slabs are set parallel to each other. Looking along the flat face of the central stone we see the outline of Ben Corra in Jura, some 30 km away. Looking along the direction indicated by the line of stones and the kist, we see off-shore the island of Cara.

About 1800 BC, the obliquity of the ecliptic was slightly different in value from the value it has now. It had, in fact, a value near to 23◦ 54' . This would, therefore, be the maximum northerly and southerly declination of the Sun at that era on midsummer’s and midwinter’s day respectively (for the northern hemisphere). The corresponding values of the midsummer and midwinter sunset azimuths indicate that on midsummer’s day, from a pre-determined position near the stones, the Sun would be seen to set behind Ben Corra in the manner indicated in figure 1 and such that momentarily a small part of its upper edge would reappear further down the slope. Midwinter’s day would be known to have arrived when the megalithic observers saw the Sun set behind Cara Island in the manner shown. We do not know the exact procedure adopted by the megalithic astronomers but it is likely to have been based on the following method. As the Sun sets on the western horizon, the observer, by moving along the line at right angles to the Sun’s direction, could insert a stake at the position he/she had to occupy in order to see the upper edge or limb of the Sun reappear momentarily behind the mountain slope indicated by the stone alignment (figure 1). This procedure would be repeated for several evenings until midsummer’s day. On each occasion the stake would have to be moved further left or a fresh one put in, but by midsummer’s eve, a limit would be reached because the Sun would be setting at its maximum declination north. On the evenings thereafter, the positioning of the pegs would be retraced. In this way it would be known when midsummer’s day occurred. It may be noted in passing that with a distant foresight such as the mountain 30 km or so away, even a shift of 12 arc sec in the

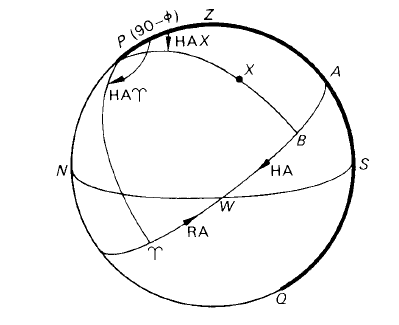

Figure2. The celestial sphere illustrating local sidereal time.

Sun’s setting the position will mean a stake-shift of the order of 2 m. This demonstrates the sensitivity of the method and the ingenuity of this ancient culture.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)