تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Measuring distance in the Solar System: The Moon

المؤلف:

A. Roy, D. Clarke

المصدر:

Astronomy - Principles and Practice 4th ed

الجزء والصفحة:

p 125

30-7-2020

1929

Measuring distance in the Solar System: The Moon

The Moon is the only natural object in the Solar System whose distance can be found accurately using the classical parallax method.

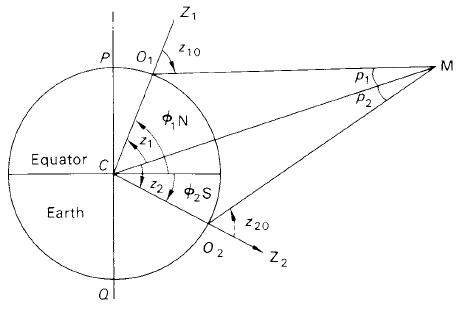

In principle, it involves the simultaneous measurement of the meridian zenith distance of the Moon at two observatories with the same longitude but widely separated in latitude. The wide latitude separation provides a reasonably long base-line Let observatories O1 and O2 have latitudes ∅1 N and ∅2 S. Let the meridian zenith distances of the Moon be z10 and z20 at these two observatories, that is Z10 = ∠Z1O1M and Z20 = ∠Z2O2M (see figure 1).

Then if z1 and z2 are the true (i.e. geocentric) zenith distances for observatories O1 and O2 respectively, with p1 and p2 the parallactic angles O1MC and O2MC, we may write

∅1 + ∅2 = z1 + z2 (1)

z1 = z10 − p1 z2 = z20 − p2 (2)

p1 = P sin z10 p2 = P sin z20 (3)

where P is the value of the Moon’s horizontal parallax when the observations are made.

By equations (3),

P = (p1 + p2)/(sin z10 + sin z20).

By equations (2),

p1 + p2 = z10 + z20 − (z1 + z2).

By equation (1), then, we have

P = [z10 + z20 − (∅1 + ∅2)]/(sin z10 + sin z20) (4)

Figure 1. Measurement of the Moon’s distance by observations from two sites.

so that P may be calculated from known and measured quantities. Knowing the radius of the Earth.

In practice, the procedure is complicated by a number of factors. The observatories are never quite on the same meridian of longitude so that a correction has to be made for the change in the Moon’s declination in the time interval between its transits across the two observatories’ respective meridians. In addition, theMoon is not a point source of light. Agreement, therefore, has to be made between the observatories as to which crater to observe, a correction thereafter giving the distance between the centres of Earth and Moon.

Due allowance must be made for the individual instrumental errors and the local values of refraction. In the case of the Moon, its parallax is so large that any residual error is not great. Since the advent of radar, laser methods and lunar probes, including lunar artificial satellites, the Moon’s distance can be measured very accurately. The limiting accuracy is partly due to the accuracy with which the velocity of light is known but also involves the accuracy with which the Earth observing stations’ geodetic positions are known. Uncertainties are of the order of 0·1 of a metre, the average

distance being 384 400 kilometres.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)