Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Gender and noun class

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

90-6

20-1-2022

1702

Gender and noun class

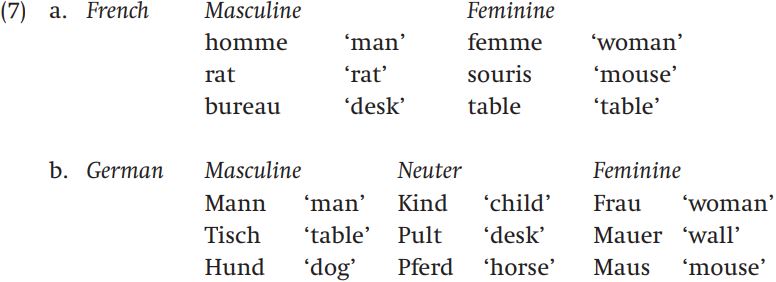

If you’ve studied French, Spanish, German, Latin, Russian, or another Indo-European language, you’re probably familiar with the concept of gender. In languages that have grammatical gender nouns are divided into two or more classes with which other elements in a sentence – for example, articles and adjectives – must agree. We use French and German as our examples here:

French has two genders, masculine and feminine. German has three genders, masculine, feminine, and neuter. While sometimes the real world sex of the noun’s referent determines the grammatical gender of the noun – that is, the class that the noun belongs to – in many more cases nouns are assigned to genders with some degree of arbitrariness. So while the words for ‘man’ and ‘woman’ in both languages are masculine and feminine respectively, in accordance with natural gender, the assignment of various animal names to gender classes is quite arbitrary. Rats, mice, dogs, and horses of course have natural gender – in the real world they must be either male or female – but French and German grammar places them in a gender independent of their natural genders. In French, rats are masculine, but mice feminine. In German, dogs are masculine, horses neuter, and mice feminine. Inanimate nouns have no natural gender, but they are nevertheless classed as either masculine or feminine in French, and as any of the three genders in German.

Assignment to gender classes sometimes seems completely arbitrary, but it is not always as arbitrary as you might think. For example, in German all nouns derived with the derivational suffixes -ung, -keit, -heit, and -schaft are feminine, regardless of the gender of their bases. All of these suffixes form abstract nouns, so it’s possible to say that derived abstract nouns are always feminine. Similarly, the diminutive suffixes -chen and -lein produce neuter nouns, regardless of the base they attach to. In other languages, nouns may be assigned to a gender based on their phonological shape. For example, the Afro-Asiatic language Hausa has masculine and feminine genders. Nouns for males are masculine and those for females are feminine in accordance with natural gender, but the rest of the nouns are assigned to one of the classes by the phonological form of the base: nouns that end in -aa are feminine, and everything else is masculine.

For many nouns in French and German, neither the meaning of the noun nor its phonological form signals its gender. In other words, there are no suffixes or other marks right on the nouns to tell us their genders (life would be much easier for second language learners of these languages if there were!). Rather, we can tell what the gender of the noun is by other elements in a sentence that are in agreement with a noun. So in French, the definite article le is used with masculine nouns (le bureau), and la with feminines (la table). Similarly, in German the definite article der is used with masculines (der Tisch), das with neuters (das Pferd) and die with feminines (die Maus).

The gender systems we are most familiar with are typical of IndoEuropean languages, and occur in other language families as well, but there are many languages outside of Indo-European that exhibit genders or noun classes based on distinctions other than (or in addition to) masculine, feminine, and neuter. Languages may have human and nonhuman classes or classes for rational beings as opposed to everything else. In the Algonquian family of languages, noun classes are based not on masculine and feminine but on animacy. Words for people belong to the animate class, but so, for example, do spirits and animals. And while most words for inanimate things belong to the inanimate class, some belong to the animate class; for example the nouns for ‘snowshoe’ and ‘button’ in the Algonquian language Ojibwa belong to the animate noun class . In other words, while there is a partial semantic basis for the two classes, assignment to the animate and inanimate classes can still be arbitrary.

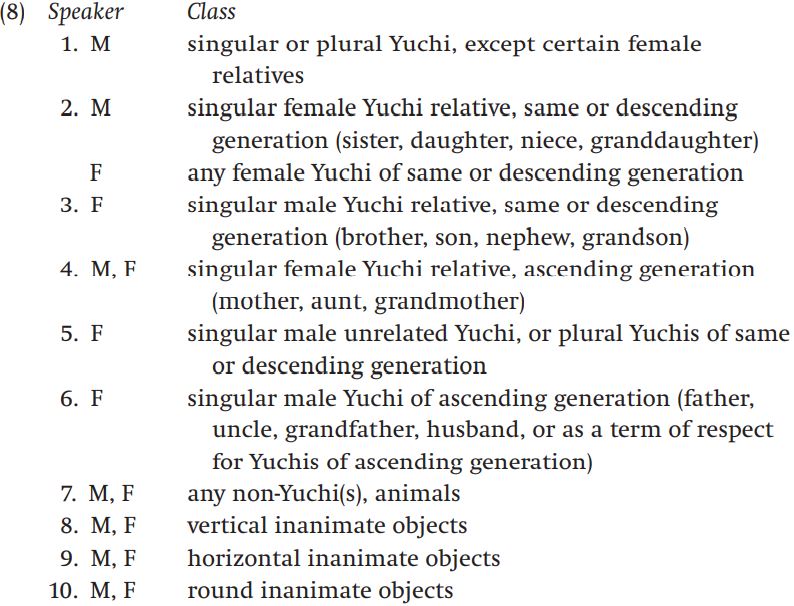

Languages are not limited to two or three classes. Consider the language Yuchi, spoken in Oklahoma: (Mithun 1999: 103):

In Yuchi, nouns fall into classes based on whether they denote humans, animals, or inanimate objects with certain shapes. For example, Class 1 contains nouns used by men to denote Yuchi people, except close female relatives. The gender of a noun is indicated by a number of things, one of which is the article suffix used with the noun. For example, gɔn̛ tɛ-nɔ̧́ means ‘the Yuchi man’ and gɔn̛ tɛ-wənɔ̧́ ‘the non-Yuchi man’. ‘The tree’ is yá-fa but ya-ʔɛ is ‘the log’. Class 7 ́ contains nouns used by either men or women to denote animals or people who are not Yuchi. Other classes distinguish Yuchis from other humans, and Yuchis related to the speaker from those unrelated to the speaker.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)