Lexical strata: English

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

168-9

الجزء والصفحة:

168-9

25-1-2022

25-1-2022

2353

2353

What we have seen s that building complex words is frequently accompanied by phonological effects such as assimilation or vowel harmony. In this section we will see that in some languages such phonological effects do not apply uniformly across the entire lexicon of the language, but instead are confined to a subset of the lexicon. Indeed some languages have two or more different layers to their lexicons which behave differently in terms of phonological effects. In this section we will look at three such languages, English, Dutch, and French.

English

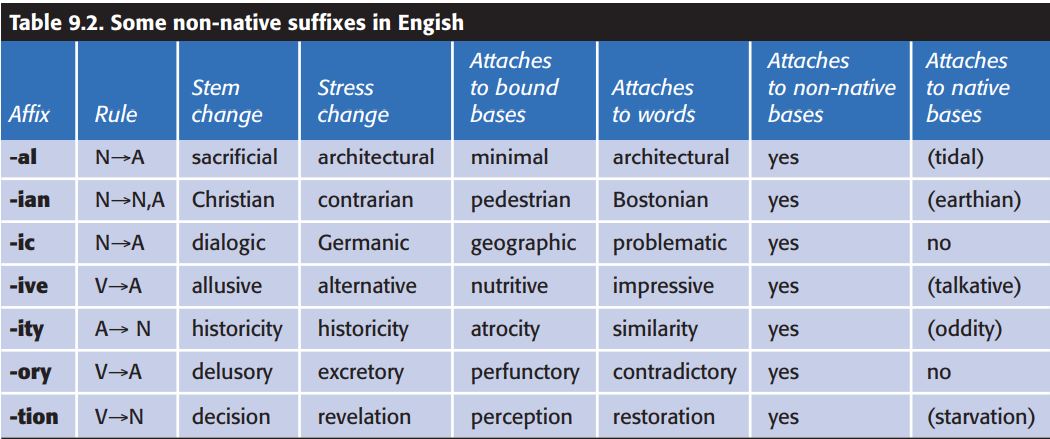

the suffix -tion is associated with complex and partially unpredictable allomorphy, both of the suffix itself and of the bases it attaches to. It turns out that it’s not the only suffix in English that acts that way. Consider the examples in table 9.2.

All seven of the suffixes in table 9.2 are non-native to English. Specifically, they were borrowed from Latin either directly or by way of French. All of them are like -tion in showing complex patterns of allomorphy. When they are added to bases, the final consonants of those bases sometimes change:

The stress pattern on the base often changes as well:

Furthermore, all of these suffixes can attach either to bound bases or to full words. And all of them prefer to attach to bases that are themselves non-native to English. The items in the last column in the table are in parentheses because they are among the few native bases (sometimes the only one) on which these affixes can be found.

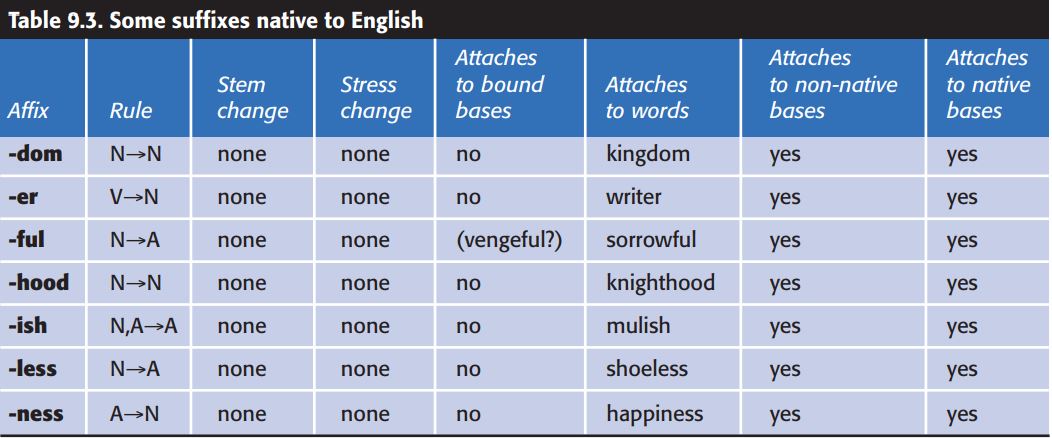

If we now look at suffixes that are native to English – that is, suffixes that were present in Old English, rather than borrowed from some other language – we find quite a different pattern: consider table 9.3.

When these suffixes attach to bases, they change neither the sounds of those bases nor their stress pattern:

Typically they attach freely to either native or non-native bases, but they do not attach to bound bases; the word vengeful is in parentheses because it seems to be the only example where one of these suffixes might be said to be attached to a bound base, but it’s a questionable example, since venge, according to the OED, is an obsolete word in English.

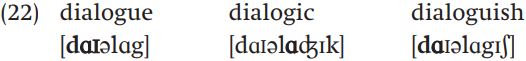

In fact, the different behavior of the two sets of affixes can be nicely illustrated by comparing the suffixes -ic and -ish, both of which can take nouns and make adjectives from them. Compare the adjectives they form from the non-native base dialogue:

The suffixes themselves differ only in their final sound, but -ic both changes the final consonant of its base and causes its stress pattern to change, whereas -ish has neither effect. What this illustrates is that English derivational morphology exhibits two different lexical strata, layers of lexeme formation that display different phonological behavior.

We can make one more interesting observation about the lexical strata of English. Consider the derived words in (23):

Not every suffix can attach to other suffixed words in English, but sometimes we can get complex words with two or more layers of suffixes. As (23) shows, we can often affix a non-native suffix to a base that already has a non-native suffix, and similarly put a native suffix on a base that already has a native suffix. Further, we can often stack up two suffixes if the first (the innermost in terms of structure) is non-native and the second native. What’s much more difficult – although not absolutely impossible - – is to first affix a native suffix and then put a nonnative suffix outside it. This makes perfect sense: non-native suffixes prefer to attach to non-native bases. Once a native suffix has been added to a base, regardless of whether that base was native or non-native to begin with, the derived word counts as a native word as far as further affixation is concerned.

The affixes we’ve looked at here show very clear and very different behavior, which justifies our saying that English derivational morphology displays two different lexical strata. To be honest, not all suffixes in English are as easily classified as the ones we’ve looked at in this section. While the other affixes that are native to English behave much as those discussed here, this is not the case with all non-native affixes. Some affixes that are borrowed, and therefore should be part of the non-native stratum of English, behave more like native affixes in that they have no phonological effects on their bases and attach indiscriminately to both native and non-native bases. We will not go further into the intricacies of 172 INTRODUCING MORPHOLOGY English derivation here, but merely point out that while the outlines of the two strata are quite clear, there is some blurring between them.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة