Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Studying meaning

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

الجزء والصفحة:

1-1

9-2-2022

1242

Studying meaning

Overview

This topic is about how English enables people who know the language to convey meanings. Semantics and pragmatics are the two main branches of the linguistic study of meaning. Both are named in the title and they are going to be introduced here. Semantics is the study of the “toolkit” for meaning: knowledge encoded in the vocabulary of the language and in its patterns for building more elaborate meanings, up to the level of sentence meanings. Pragmatics is concerned with the use of these tools in meaningful communication. Pragmatics is about the interaction of semantic knowledge with our knowledge of the world, taking into account contexts of use.

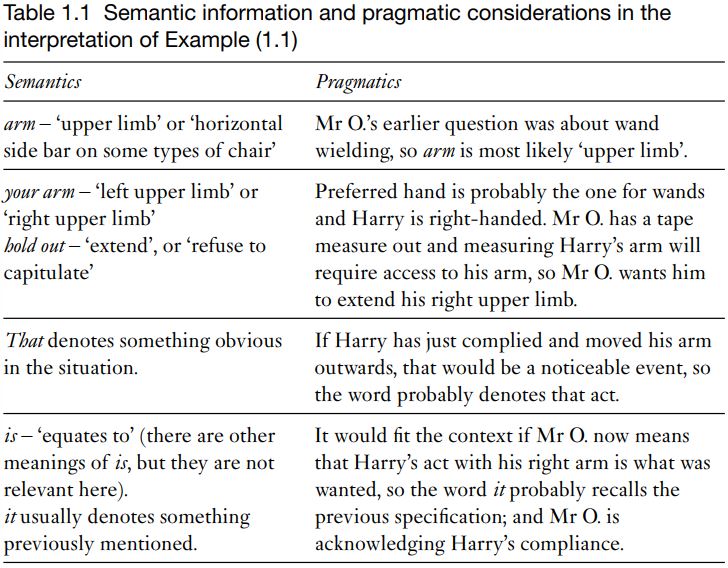

Example (1.1) is going to be used in an initial illustration of the difference between semantics and pragmatics, and to introduce some more terms needed for describing and discussing meanings.

Language is for communicating about the world outside of language. English language expressions like arm and your arm and hold out are linked to things, activities and so on. A general-purpose technical term that will appear fairly often is denote. It labels the connections between meaningful items of language and aspects of the world – real or imagined – that language users talk and write about. Hold out your arm denotes a situation that the speaker wants; hold out denotes an action; arm denotes a part of a person; your arm denotes ‘the arm of the person being spoken to’; and so on. An expression is any meaningful language unit or sequence of meaningful units, from a sentence down: a clause, a phrase, a word, or meaningful part of a word (such as the parts hope, -ful and -ly that go together to make the word hopefully; but not the ly at the end of holy, because it is not a separately meaningful part of that word.)

That’s it at the end of Example (1.1) is an expression which can mean ‘OK (that is correct)’, or ‘There is no more to say’, but for the moment I want to discuss the expressions That and it separately: what do they denote? That denotes something which is obvious to whomever is being addressed – perhaps the act of holding out an arm – yes, acts and events can be spoken of as if they were “things”. (There is a question over which arm, since most people have two.) Other possibilities for what that could denote are the arm itself, or some other thing seen or heard in the surroundings. The word it usually denotes something that has recently been spoken about: the arm or the act of holding it out are the two candidates in (1.1). Without knowing the context in which (1.1) occurred, its meaning cannot confidently be explained much more than this.

In fact, (1.1) is a quotation from the first of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books.1 It is spoken to Harry by Mr Ollivander, a supplier of fine wands. In the book it comes just after Mr Ollivander, taking out a tape measure, has asked Harry ‘Which is your wand arm?’ The contextual information makes it pretty certain that your arm denotes Harry’s wand arm (his right arm, Harry guesses, as he is right-handed). Immediately after Mr Ollivander has said what was quoted in (1.1), he begins to measure Harry for a wand. This makes it easy in reading the story to understand that Harry complied with the request to hold out his arm, and “That’s it” was said to acknowledge that Harry had done what Mr O. had wanted. This acknowledgement can be unpacked as follows: That denotes Harry’s act done in response to the request – an obvious, visible movement of his arm, enabling Mr O. to use the measuring tape on Harry’s arm; it denotes the previous specification of what Harry was asked to do, the act of holding out his arm; and the ’s (a form of is) indicates a match: what he had just done was what he had been asked to do. Table 1.1 summarizes this, showing how pragmatics is concerned with choices among semantic possibilities, and how language users, taking account of context and using their general knowledge, build interpretations on the semantic foundation.

The reasoning in the right-hand column of Table 1.1 fits a way of thinking about communication that was introduced by the philosopher H. P. Grice (1989 and in earlier work) and is now very widely accepted in the study of pragmatics.

According to this view, human communication with language is not like pressing buttons on a remote control and thereby affecting circuits in a TV set. Instead it requires active collaboration on the part of any person the message is directed to, the addressee (such as a reader of (1.1) in its context in J. K. Rowling’s book, or a listener, like Harry Potter hearing what Mr Ollivander said in (1.1)). The addressee has the task of trying to guess what the sender (the writer or speaker) intends to convey, and as soon as the sender’s intention has been recognized, that’s it – the message has been communicated. The sender’s task is to judge what needs to be written or said to enable the addressee to recognize what the sender wants to communicate.

There are three consequences of this:

. There are different ways of communicating the same message (and the same string of words can convey different messages) because it depends on what, in the context at the time, will enable the addressee to recognize the sender’s intention. It is not as undemanding as remote control of a TV set.

. The active participation of the addressee sometimes allows a lot to be communicated with just a little having been said or written.

. Mistakes are possible. In face-to-face interactions the speaker can monitor the listener’s (or listeners’) reactions – whether these are grins or scowls, or spoken responses, or actions like Harry obediently holding out his arm – to judge whether or not the sending intention has been correctly guessed, and can then say more to cancel misunderstandings and further guide the addressee towards what is intended. Such possibilities are reduced but still present in telephone conversations and, to a lesser extent, in internet chat exchanges; even writers may eventually discover something about how what they wrote has been understood, and then write or say more.

Competent users of a language generally employ it without giving thought to the details of what is going on. Linguists – and semantics and pragmatics are branches of linguistics – operate on the assumption that there are interesting things to discover in those details. This approach can seem like an obsession with minutiae, and maybe you felt that way when the first example was discussed. It is a project of trying to bring to accessible consciousness knowledge and skills that are most of the time deployed automatically. This close inspection of bits of language and instances of usage – even quite ordinary ones – is done with a view to understanding how they work, which can be fascinating.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)