Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Making statements more precise

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

38-4

16-3-2022

1633

Making statements more precise

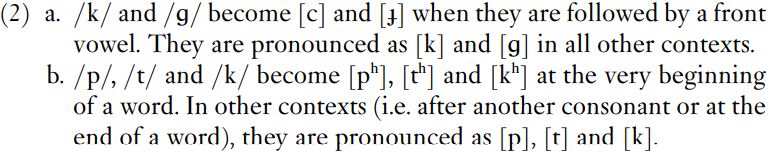

The next question is how we should express these generalizations. Having established that certain sounds are allophones of the same phoneme, and that they are in complementary distribution, we might write a statement like (2) to say what happens to the phoneme or phonemes in question, and where.

These statements express the main generalization in each case. However, making a statement in normal English can be unclear and unwieldy, so phonologists typically use a more formal notation which helps us to work out exactly what is being said; it is easier that way to identify what a counterexample would be, and to see what predictions are being made. The English statement also does not tell us why /p/, /t/ and /k/ are affected, rather than just one or two of them; or why these three sounds should behave similarly, rather than /p/, /s/ and /r/, for instance. Similarly, we cannot see what /k/ and/g/ have in common, or indeed what the resulting allophones have in common, simply by looking at the phoneme symbols.

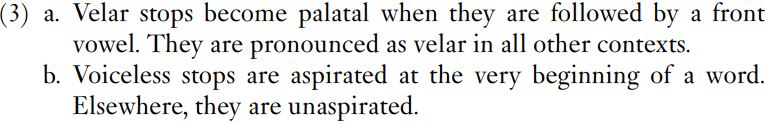

Introducing the articulatory descriptions , Immediately makes our statements more adequate and more precise, as we can now express what particular sets of sounds have in common (3).

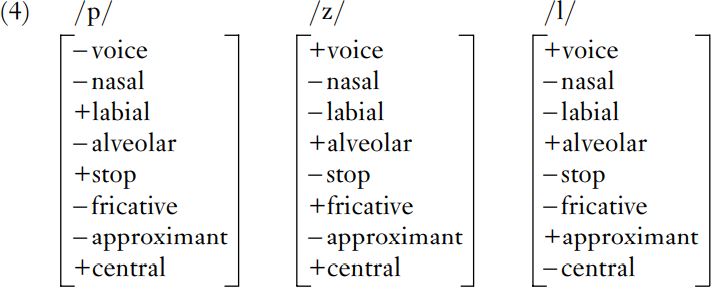

We can take this one step further by regarding each of the articulatory descriptions as a binary feature: that is, a sound is either voiceless or voiced, and these are opposites; similarly, a sound is either nasal or not nasal. Instead of voiced and voiceless, or oral and nasal, we can then write [+voice] and [– voice], and [– nasal] and [+nasal]. This may seem like introducing needless complexity; but once you are used to the notation, it is much easier to compare these rather formal statements, and to see what the important aspects are.

These distinctive features allow each segment to be regarded as a simultaneously articulated set, or matrix, of binary features, as shown in (4).

These features, however, are not entirely satisfactory. They do describe phonetic characteristics of sounds; but we are trying to provide a phonological description, not a phonetic one, and one interesting phonological fact is that features and phonemes fall into classes. For instance, the matrices in (4) have to include values for all three of the features [stop], [fricative] and [approximant], despite the fact that any sound can be only one of these. Together, they provide a classification for manner of articulation; but (4) lists them all as if they were as independent as [nasal], [voice] and [alveolar]. Similarly, in (4) values are given for [labial] and [alveolar], and we would have to add [labio-dental], [dental], [postalveolar], [palatal], [velar] and [glottal] for English alone: but again, it is simply not possible for a single consonant to be both labiodental or velar, for instance, or both alveolar and labial. We are missing the generalization that together, this group of features makes up the dimension of place of articulation.

One possible way of overcoming this lack of economy in the feature system is to group sets of features together, and write redundancy rules to show which values can be predicted. Redundancy rules take the shape shown in (5).

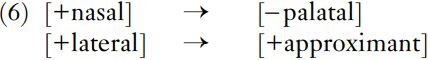

The first rule says ‘if a segment is a stop, it cannot also be either a fricative or an approximant’. All these redundancy rules are universal – that is, they hold for all human languages, and are in a sense statements of logical possibilities. Particular languages may also rule out combinations of features which are theoretically possible, and which may occur routinely in many other languages. Two language-specific redundancy rules for English are given in (6): the first tells us that English has no palatal nasal (although Italian and French do), and the second, that English has only lateral approximants (though Welsh, for instance, has also a lateral fricative). These redundancy rules cannot be written the other way around: it would not be accurate to say that non-palatals are all nasal in English, or that all approximants are lateral.

While we should expect to have to state redundancy rules of the sort in (6), since these express quirks of particular languages, it seems unfortunate that our feature system is not structured so as to factor out the universal redundancies in (5). However, to produce a better phonological feature system, we first need to spell out what we want such a system to achieve.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)