Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Rules and constraints

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

62-5

17-3-2022

1491

Rules and constraints

Most interactions of phonology with morphology, the part of linguistics which studies how words are made up of meaningful units, like stems and suffixes, although the overlap between the two areas, commonly known as morphophonemics, has been extremely important in the development of phonological theory over the last fifty years. Indeed, the difference between phonetically conditioned allophony and neutralization, which involve only the phonetics and phonology, and cases where we also need to invoke morphological issues, is central to one of the most important current debates in phonology.

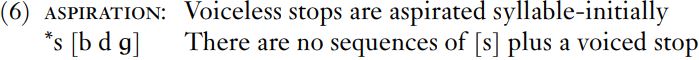

Generalizations about the distribution of allophones were stated in terms of rules, the assumption being that children learn these rules as they learn their native language, and start to see that forms fall into principled categories and behave according to regular patterns. Rule-based theories also include constraints – static, universal or language-specific statements of possibility in terms of segment shapes or combinations, and phonotactic constraints. However, since the mid-1990s, an alternative approach has developed, as part of the phonological theory called Optimality Theory. Phonologists working in Optimality Theory do not write rules; they express all phonological generalizations using constraints. Instead of saying that a particular underlying or starting form changes into something else in a particular environment, which is what rules do, constraints set out what must happen, or what cannot happen, as in the examples in (6), which express regularities we have already identified for English.

In most versions of Optimality Theory, all the constraints are assumed to be universal and innate: children are born with the constraints already in place, so all they have to do is work out how important each constraint is in the structure of the language they are learning, and produce a ranking accordingly. For an English-learning child, the two constraints in (6) must be quite important, because it is true that voiceless stops are aspirated at the beginnings of syllables, and there are no sequences of [s] plus a voiced stop; consequently, English speakers will rank these two constraints high. However, for children learning a language without aspiration, or with clusters of [s] plus voiced stop, these constraints will not match the linguistic facts they hear; they will therefore be ranked low down in the list, so they have no obvious effect. On the other hand, a child learning German, say, would have to pay special attention to a constraint banning voiced stops from the ends of words, since this is a position of neutralization in German, permitting only voiceless stops; but a child learning English will rank that constraint very low, as words like hand, lob, fog show that this constraint does not affect the structure of English.

Constraints of this sort seem to work quite well when we are dealing only with phonetic and phonological factors, and may be appropriate alternatives to rules in the clearly conditioned types of allophonic variation we have considered, and for neutralization. However, they are not quite so helpful when it comes to the interaction of morphology and phonology, where alternations are often not clearly universally motivated, but involve facts about the structure and lexical items of that specific language alone. Analyzing such cases using Optimality Theory may require a highly complex system of constraints, as we will have to accept that all the possible constraints for anything that could ever happen in any language are already there in every child’s brain at birth. These issues are likely to lead to further debate in phonology in future years.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)