Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The concerns of phonology

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

8-1

23-3-2022

1759

The concerns of phonology

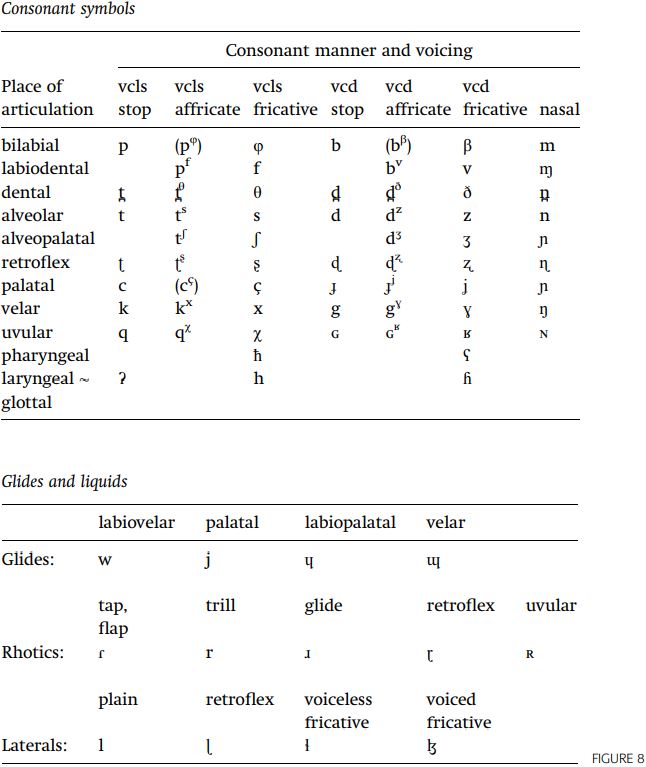

As a step towards understanding what phonology is, and especially how it differs from phonetics, we will consider some specific aspects of sound structure that would be part of a phonological analysis. The point which is most important to appreciate at this moment is that the “sounds” which phonology is concerned with are symbolic sounds – they are cognitive abstractions, which represent but are not the same as physical sounds.

The sounds of a language. One aspect of phonology investigates what the “sounds” of a language are. We would want to take note in a description of the phonology of English that we lack the vowel [ø] that exists in German in words like schön ‘beautiful,’ a vowel which is also found in French (spelled eu, as in jeune ‘young’), or Norwegian (øl ‘beer’). Similarly, the consonant [θ] exists in English (spelled th in thing, path), as well as Icelandic, Modern Greek, and North Saami), but not in German or French, and not in Latin American Spanish (but it does occur in Continental Spanish in words such as cerveza ‘beer’).

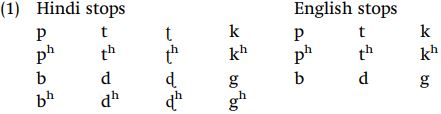

Sounds in languages are not just isolated atoms; they are part of a system. The systems of stops in Hindi and English are given in (1).

The stop systems of these languages differ in three ways. English does not have a series of voiced aspirated stops like Hindi [bh dh ɖh gh ], nor does it have a series of retroflex stops [ʈ ʈh ɖ ɖh ]. Furthermore, the phonological status of the aspirated sounds [ph t h kh ] is different in the languages, as discussed in chapter 2, in that they are basic lexical facts of words in Hindi, but are the result of applying a rule in English.

Rules for combining sounds. Another aspect of language sound which a phonological analysis takes account of is that in any language, certain combinations of sounds are allowed, but other combinations are systematically impossible. The fact that English has the words [bɹɪk] brick, [bɹejk] break, [bɹɪdʒ ] bridge, [bɹɛd] bread is a clear indication that there is no restriction against having words that begin with the consonant sequence br; besides these words, one can think of many more words beginning with br such as bribe, brow and so on. Similarly, there are many words which begin with bl, such as [bluw] blue, [bleʔn̩ t] blatant, [blæst] blast, [blɛnd] blend, [blɪŋk] blink, showing that there is no rule against words beginning with bl. It is also a fact that there is no word *[blɪk]1 in English, even though the similar words blink, brick do exist. The question is, why is there no word *blick in English? The best explanation for the nonexistence of this word is simply that it is an accidental gap – not every logically possible combination of sounds which follows the rules of English phonology is found as an actual word of the language.

Native speakers of English have the intuition that while blick is not a word of English, it is a theoretically possible word of English, and such a word might easily enter the language, for example via the introduction of a new brand of detergent. Sixty years ago the English language did not have any word pronounced [bɪk], but based on the existence of words like big and pick, that word would certainly have been included in the set of nonexistent but theoretically allowed words of English. Contemporary English, of course, actually does have that word – spelled Bic – which is the brand name of a ballpoint pen.

While the nonexistence of blick in English is accidental, the exclusion from English of many other imaginable but nonexistent words is based on a principled restriction of the language. While there are words that begin with sn like snake, snip, and snort, there are no words beginning with bn, and thus *bnick, *bnark, *bniddle are not words of English. There simply are no words in English which begin with bn. Moreover, native speakers of English have a clear intuition that hypothetical *bnick, *bnark, *bniddle could not be words of English. Similarly, there are no words in English which are pronounced with pn at the beginning, a fact which is not only demonstrated by the systematic lack of words such as *pnark, *pnig, *pnilge, but also by the fact that the word spelled pneumonia which derives from Ancient Greek (a language which does allow such consonant combinations) is pronounced [nʌ̍monjə] without p. A description of the phonology of English would provide a basis for characterizing such restrictions on sequences of sounds.

Variations in pronunciation. In addition to providing an account of possible versus impossible words in a language, a phonological analysis will explain other general patterns in the pronunciation of words. For example, there is a very general rule of English phonology which dictates that the plural suffix on nouns will be pronounced as [ɨz], represented in spelling as es, when the preceding consonant is one of a certain set of consonants including [ʃ] (spelled sh) as in bushes, [tʃ ] (spelled as ch) as in churches, and [dʒ ] (spelled j, ge, dge) as in cages, bridges. This pattern of pronunciation is not limited to the plural, so despite the difference in spelling, the possessive suffix s 2 is also subject to the same rules of pronunciation: thus, plural bushes is pronounced the same as the possessive bush’s, and plural churches is pronounced the same as possessive church’s.

This is the sense in which phonology is about the sounds of language. From the phonological perspective, a “sound” is a specific unit which combines with other such specific units, and which represents physical sounds. What phonology is concerned with is how sounds behave in a grammar.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)