Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The importance of correct underlying forms

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

80-4

26-3-2022

2264

The importance of correct underlying forms

Neutralizing rules, on the other hand, are ones where two or more underlyingly distinct segments have the same phonetic realization in some context because a rule changes one phoneme into another – thus the distinction of sounds is neutralized. This means that if you look at a word in this neutralized context, you cannot tell what the underlying segment is. Such processes force you to pay close attention to maintaining appropriate distinctions in underlying forms.

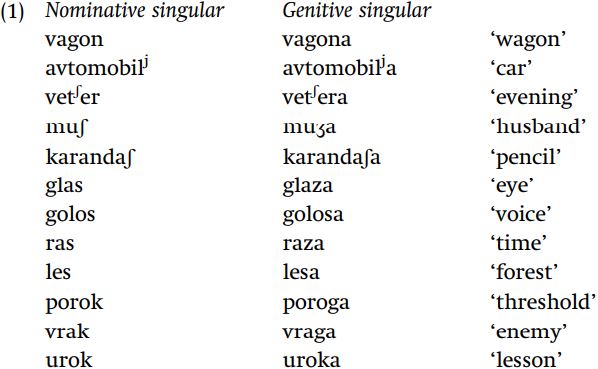

Consider the following examples of nominative and genitive forms of nouns in Russian, focusing on the final consonant found in the nominative.

To give an explanation for the phonological processes at work in these data, you must give a preliminary description of the morphology. While morphological analysis is not part of phonology per se, it is inescapable that a phonologist must do a morphological analysis of a language, to discover the underlying form.

In each of the examples above, the genitive form is nearly the same as the nominative, except that the genitive also has the vowel [a] which is the genitive singular suffix. We will therefore assume as our initial hypothesis that the bare root of the noun is used to form the nominative case, and the combination of a root plus the suffix -a forms the genitive. Nothing more needs to be said about examples such as vagon ~ vagona, avtomobilj ~ avtomobilj a, or vetʃ er ~ vetʃ era, where, as it happens, the root ends with a sonorant consonant. The underlying forms of these noun stems are presumably /vagon/, /avtomobilj /, and /vetʃ er/: no facts in the data suggest anything else. These underlying forms are thus identical to the nominative form. With the addition of the genitive suffix -a this will also give the correct form of the genitive.

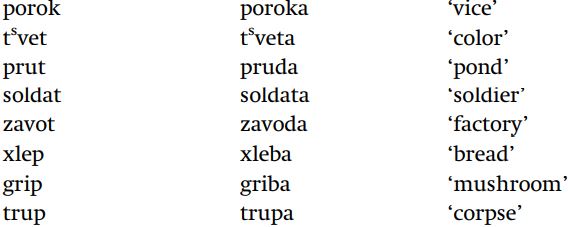

There are stems where the part of the word corresponding to the root is the same in all forms of the word: karandaʃ ~ karandaʃa, golos ~ golosa, les ~ lesa, urok ~ uroka, porok ~ poroka, t s vet ~ t s veta, soldat ~ soldata, and trup ~ trupa. However, in some stems, there are differences in the final consonant of the root, depending on whether we are considering the nominative or the genitive. Thus, we find the differences muʃ ~ muʒa, ~ glas ~ glaza, porok ~ poroga, vrak ~ vraga, prut ~ pruda, and xlep ~ xleba. Such variation in the phonetic content of a morpheme (such as a root) is known as alternation. We can easily recognize the phonetic relation between the consonant found in the nominative and the consonant found in the genitive as involving voicing: the consonant found in the nominative is the voiceless counterpart of the consonant found in the genitive. Not all noun stems have such an alternation, as we can see by pairs such as karandaʃ ~ karandaʃa, les ~ lesa, urok ~ uroka, soldat ~ soldata, and trup ~ trupa. We have now identified a phonological problem to be solved: why does the final consonant of some stems alternate in voicing? And why do we find this alternation with some stems, but not others?

The next two steps in the analysis are intimately connected; we must devise a rule to explain the alternations in voicing, and we must set up appropriate underlying representations for these nouns. In order to determine the correct underlying forms, we will consider two competing hypotheses regarding the underlying form, and in comparing the predictions of those two hypotheses, we will see that one of those hypotheses is clearly wrong.

Suppose, first, that we decide that the form of the noun stem which we see in the nominative is also the underlying form. Such an assumption is reasonable (it is, also, not automatically correct), since the nominative is grammatically speaking a more “basic” form of a noun. In that case, we would assume the underlying stems /glas/ ‘eye,’ /golos/ ‘voice,’ /ras/ ‘time,’ and /les/ ‘forest.’ The problem with this hypothesis is that we would have no way to explain the genitive forms glaza, golosa, raza, and lesa: the combination of the assumed underlying roots plus the genitive suffix -a would give us *glasa, golosa, *rasa, and lesa, so we would be right only about half the time. The important step here is that we test the hypothesis by combining the supposed root and the affix in a very literal-minded way, whereupon we discover that the predicted forms and the actual forms are different.

We could hypothesize that there is also a rule voicing consonants between vowels (a rule like one which we have previously seen in Kipsigis):

While applying this rule to the assumed underlying forms /glas-a/, /golos-a/, /ras-a/, and /les-a/ would give the correct forms glaza and raza, it would also give incorrect surface forms such as *goloza and *leza. Thus, not only is our first hypothesis about underlying forms wrong, it also cannot be fixed by positing a rule of consonant voicing.

You may be tempted to posit a rule that applies only in certain words, such as eye, time, and so on, but not voice, forest, etc. This misconstrues the nature of phonological rules, which are general principles that apply to all words of a particular class – most generally, these classes are defined in terms of phonological properties, such as “obstruent,” “in word-final position.” Rules which are stated as “only applying in the following words” are almost always wrong.

The “nominative is underlying” hypothesis is fundamentally wrong: our failure to come up with an analysis is not because we cannot discern an obscure rule, but lies in the faulty assumption that we start with the nominative. That form has a consistent phonetic property, that any root-final obstruent (which is therefore word-final) is always voiceless, whereas in the genitive form there is no such consistency. If you look at the genitive column, the last consonant of the root portion of the word may be either voiced or voiceless.

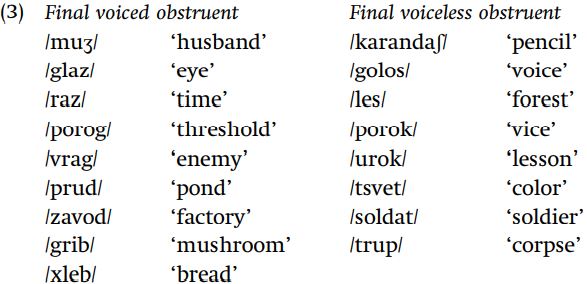

We now consider a second hypothesis, where we set up underlying representations for roots which distinguish stems which have a final voiced obstruent in the genitive versus those with a final voiceless obstruent. We may instead assume the following underlying roots

Under this hypothesis, the genitive form can be derived easily. The genitive form is the stem hypothesized in (3) followed by the suffix -a. No rule is required to derive voiced versus voiceless consonants in the genitive. That issue has been resolved by our choice of underlying representations where some stems end in voiced consonants and others end in voiceless consonants. By our hypothesis, the nominative form is simply the underlying form of the noun stem, with no suffix.

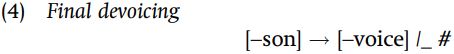

However, a phonological rule must apply to the nominative form, in order to derive the correct phonetic output. We have noted that no word in Russian ends phonetically with a voiced obstruent. This regular fact allows us to posit the following rule, which devoices any word-final obstruent.

By this rule, an obstruent is devoiced at the end of the word. As this example has shown, an important first step in doing a phonological analysis for phenomena such as word-final devoicing in Russian is to establish the correct underlying representations, which encode unpredictable information.

Whether a consonant is voiced cannot be predicted in English ([dεd] dead, [tεd] Ted, [dεt] debt), and must be part of the underlying form. Similarly, in Russian since you cannot predict whether a given root ends in a voiced or a voiceless consonant in the genitive, that information must be part of the underlying form of the root. That is information about the root, which cannot always be determined by looking at the surface form of the word itself: it must be discovered by looking at the genitive form of the noun, where the distinction between voiced and voiceless final consonants is not eliminated.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)