Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Case studies in abstract analysis

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

243-8

9-4-2022

1629

Case studies in abstract analysis

We will look in depth at two cases of abstract phonological analysis, one from Matuumbi and one from Sanskrit, where abstract underlying forms are well motivated; these are contrasted with some proposals for English, which are not well motivated. Our goal is to see that the problem of abstractness is not about the formal phonetic distance between underlying and surface forms, but rather it involves the question of how strong the evidence is for positing an abstract underlying representation.

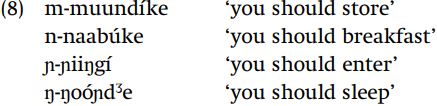

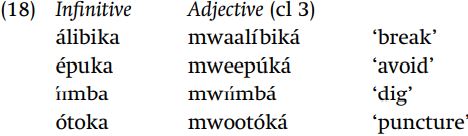

Abstract mu in Matuumbi. Matuumbi provides an example of an abstract underlying representation, involving an underlying vowel which never surfaces as such. In this language, the noun prefix which marks nouns of lexical class 3 has a number of surface realizations such as [m], [n], [ŋ], and [mw], but the underlying representation of this prefix is /mu/, despite the fact that the prefix never actually has that surface manifestation with the vowel u.

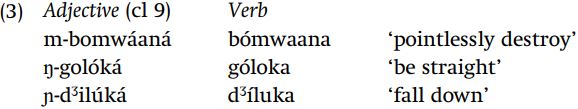

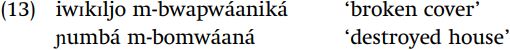

We begin with the effect which nasals have on a following consonant. Sequences of nasal plus consonant are subject to a number of rules in Matuumbi, and there are two different patterns depending on the nature of the nasal. One such nasal is the prefix /ɲ-/, marking nouns and adjectives of grammatical class 9. When this prefix comes before an underlyingly voiced consonant, the nasal assimilates in place of articulation to that consonant, by a general rule that all nasals agree in place of articulation with an immediately following consonant.

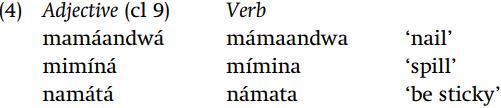

When added to a stem beginning with a nasal consonant, the nasal deletes.

The prefix /ɲ/ causes a following voiceless consonant to become voiced

Finally, /ɲ/ causes a following glide to become a voiced stop, preserving the place properties of the glide.

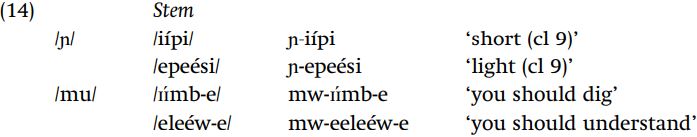

We know that the prefix is underlyingly /ɲ/ because that is how it surfaces before vowel-initial adjectives such as ɲ-epeési ‘light (cl 9),’ ɲ-iípi ‘short (cl 9).’

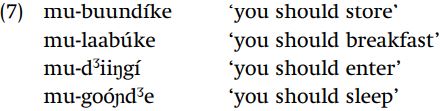

Different effects are triggered by the nasal of the prefix /mu/ which marks second-plural subjects on verbs. This prefix has the underlying form /mu/, and it can surface as such when the following stem begins with a consonant.

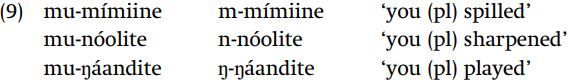

A rule deletes the vowel u preceded by m when the vowel precedes a consonant, and this rule applies optionally in this prefix. Before a stem beginning with a voiced consonant, deletion of the vowel results in a cluster of a nasal plus a consonant, and m causes nasalization of the following consonant (compare the examples in (7) where the vowel is not deleted).

This reveals an important difference between the two sets of postnasal processes. In underlying nasal C sequences such as /ɲ-bomwáaná/ ! m-bomwáaná ‘destroyed (cl 9),’ the nasal only assimilates in place of articulation to the following C, but in nasal + consonant sequences derived by deletion of u, the prefixal nasal causes nasalization of a following voiced consonant.

Another difference between /ɲC/ versus /muC/ is evident when the prefix /mu/ comes before a stem beginning with a nasal consonant. The data in (9) show that when u deletes, the resulting cluster of nasals does not undergo nasal deletion. (The reason for this is that /mu/ first becomes a syllabic nasal m̩, and nasalization takes place after a syllabic nasal.)

In comparison, class 9 /ɲ-mimíná/ with the prefix /ɲ/ surfaces as mimíná ‘spilled (cl 9),’ having undergone degemination.

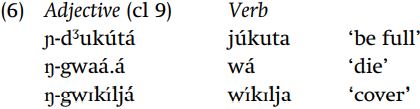

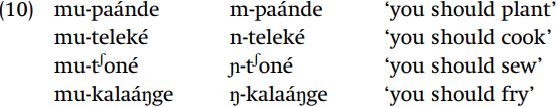

A third difference between /ɲ + C/ versus /mu+C/ emerges with stems that begin with a voiceless consonant. As seen in (10), /mu/ simply assimilates in place of articulation to the following voiceless consonant.

Remember, though, that /ɲ/ causes a following voiceless consonant to become voiced, so /ɲ-tɪnɪ ́ ká/ ->ndɪnɪ ́ ká ‘cut (cl 9).’

Finally, /mu/ causes a following glide to become a nasal at the same place of articulation as the glide.

Underlying /ɲ/, on the other hand, causes a following glide to become a voiced stop, cf. /ɲ-wɪkɪ ́ ljá/ -> ŋ-gwɪkɪ ́ ljá ‘covered (cl 9).’

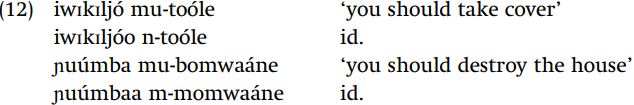

The differences between /ɲ/ and /mu/ go beyond just their effects on following consonants: they also have different effects on preceding and following vowels. In the case of /mu/, the preceding vowel lengthens when u deletes.

On the other hand, /ɲ/ has no effect on the length of a preceding vowel.

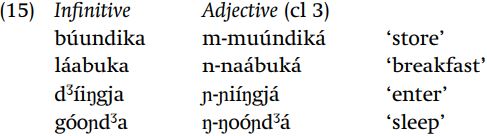

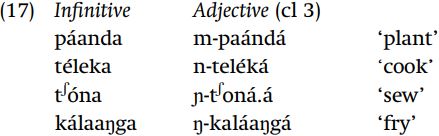

Finally, /ɲ/ surfaces as [ɲ] before a vowel and the length of the following vowel is not affected. But /mu/ surfaces as [mw] before a vowel due to a process of glide formation, and the following vowel is always lengthened.

A number of properties distinguish /mu/ from /ɲ/. Apart from the important fact that positing these different underlying representations provides a phonological basis for distinguishing these effects, our choices of underlying forms are uncontroversial, because the posited forms of the prefixes are actually directly attested in some surface variant: recall that the second-plural verbal subject prefix /mu/ can actually be pronounced as [mu], since deletion of /u/ is optional for this prefix.

Deletion of /u/ is obligatory in this prefix and optional in the subject prefix because subject prefixes have a “looser” bond to the following stem than lexical class prefixes, which are joined with the stem to form a special phonological domain.

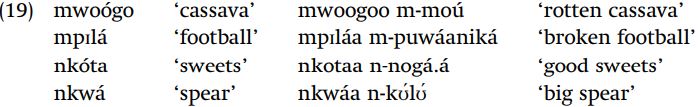

Now we are in position to discuss a prefix whose underlying representation can only be inferred indirectly. The prefix for class 3 nouns and adjectives is underlyingly /mu/, like the second-plural verbal subject prefix. Unlike the verb prefix, the vowel /u/ of the class 3 noun prefix always deletes, and /mu/ never appears as such on the surface – its underlying presence can only be inferred indirectly. A strong indication that this prefix is underlyingly /mu/ is the fact that it has exactly the same effect on a following consonant as the reduced form of the subject prefix mu has. It causes a voiced consonant to become nasalized.

It forms a geminate nasal with a following nasal.

It also does not cause a following voiceless consonant to become voiced.

Another reason to believe that this prefix is underlyingly /mu/ is that when it comes before a stem beginning with a vowel, the prefix shows up as [mw] and the following vowel is lengthened.

Under the hypothesis that the class 3 prefix is /mu/, we automatically predict that the prefix should have this exact shape before a vowel, just as the uncontroversial prefix /mu/ marking second-plural subject has.

Finally, the data in (19) show that this prefix has the same effect of lengthening the preceding vowel as the second-plural subject prefix has.

The only reasonable assumption is that this prefix is underlyingly /mu/, despite the fact that the vowel u never actually appears as such.

Direct attestation of the hypothesized underlying segment would provide very clear evidence for the segment in an underlying form, but underlying forms can also be established by indirect means, such as showing that one morpheme behaves in a manner parallel to some other which has a known and uncontroversial underlying form. Thus the fact that the class 3 prefix behaves in all other respects exactly like prefixes which are uncontroversially /mu/ suffices to justify the conclusion that the class 3 prefix is, indeed, /mu/.

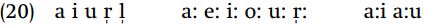

Abstract /ai/ and /au/ in Sanskrit. A significantly more abstract representation of the mid vowels [e:, o:] is required for Sanskrit. These surface vowels derive from the diphthongs /ai/, /au/, which are never phonetically manifested anywhere in the language. The surface vowels (syllabics) and diphthongs of Sanskrit are in (20).

Two things to be remarked regarding the inventory are that while the language has diphthongs with a long first element a:i, a:u, it has no diphthongs with a short first element. Second, the mid vowels only appear as long, never short. These two facts turn out to be related.

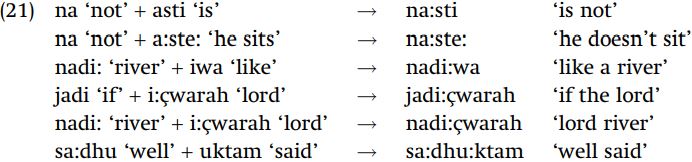

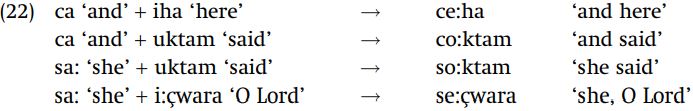

One phonological rule of the language fuses identical vowels into a single long vowel. This process operates at the phrasal level, so examples are quite easy to come by, simply by combining two words in a sentence.

A second process combines long or short a with i and u (long or short), giving the long mid vowels e: and o:.

These data point to an explanation for the distribution of vowels noted in (20), which is that underlying ai and au become e: and o:, and that this is the only source of mid vowels in the language. This explains why the mid vowels are all long, and also explains why there are no diphthongs *ai, *au. There is also a rule shortening a long vowel before another vowel at the phrasal level, which is why at the phrasal level /a:/ plus /i/ does not form a long diphthong [a:i].

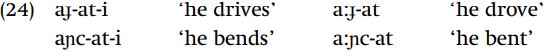

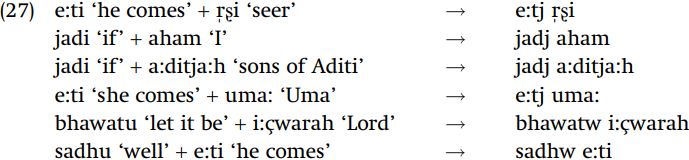

There is a word-internal context where the short diphthongs ai and au would be expected to arise by concatenation of morphemes, and where we find surface e:, o: instead. The imperfective tense involves the prefixation of a-.

If the stem begins with the vowel a, the prefix a- combines with following a to give a long vowel, just as a + a -> a: at the phrasal level.

When the root begins with the vowels i, u, the resulting sequences ai(:), au(:) surface as long mid vowels:

These alternations exemplify the rule where /ai, au/ ! [e:, o:].

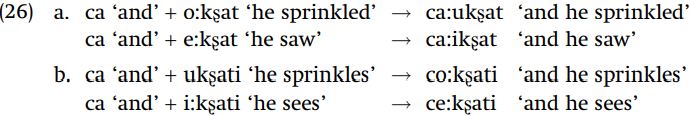

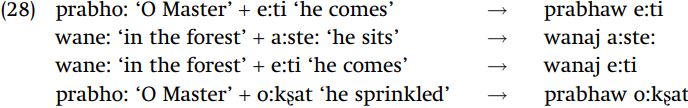

We have shown that /a + i, a + u/ surface as [e:, o:], so now we will concentrate on the related conclusion that [e:, o:] derive from underlying /ai, au/. One argument supporting this conclusion is a surface generalization about vowel combinations, that when a combines with what would surface as word initial o: or e:, the result is a long diphthong a:u, a:i.

This fusion process makes sense given the proposal that [e:] and [o:] derive from /ai/ and /au/. The examples in (26b) remind us that initial [e:,o:] in these examples transparently derive from /a + i/, /a + u/, because in these examples /a/ is the imperfective prefix and the root vowels u, i can be seen directly in the present tense. Thus the underlying forms of [ca:ukʂat] and [ca:ikʂat] are [ca#a-ukʂat] and [ca#a-ikʂat]. The surface long diphthong derives from the combination of the sequence of a’s into one long a:. The same pattern holds for all words beginning with mid vowels, even when there is no morphological justification for decomposing [e:, o:] into /a+i, a+u/

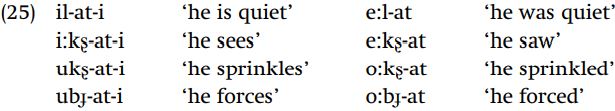

Other evidence argues for deriving surface [e:, o:] from /ai, au/. There is a general rule where the high vowels /i, u/ surface as the glides [j, w] before another vowel, which applies at the phrasal level in the following examples.

The mid vowels [e:, o:] become [aj, aw] before another vowel (an optional rule, most usually applied, can delete the glide in this context, giving a vowel sequence).

This makes perfect sense under the hypothesis that [e:, o:] derive from /ai, au/. Under that hypothesis, /wanai#a:stai/ undergoes glide formation before another vowel (just as /jadi#aham/ does), giving [wanaj#a:ste:].

Abstractness in English. Now we will consider an abstract analysis whose legitimacy has been questioned: since the main point being made here is that abstract analyses can be well motivated, it is important to consider what is not sufficient motivation for an abstract analysis.

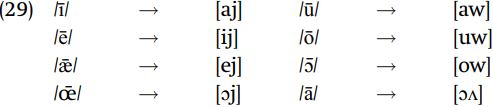

A classic case of questionable abstractness is the analysis of English [ɔj] proposed in Chomsky and Halle 1968 (SPE), that [ɔj] derives from /œ̄/. In SPE, English vowels are given a very abstract analysis, with approximately the following relations between underlying and surface representations of vowels, where /ī ū/ and so forth represent tense vowels in the transcription used there.

The first step in arguing for this representation is to defend the assumption that [aj], [aw], [ij], [uw], [ej], [ow] derive from /ī/, /ū/, /ē/, /ō/, /ǣ/, and /ɔ̄/. The claim is motivated by the Trisyllabic Laxing alternation in English which relates the vowels of divine ~ divinity ([aj] ~ [ɪ]), profound ~ profundity ([aw] ~ [ə]), serene ~ serenity ([ij] ~ [ε]), verbose ~ verbosity ([ow] ~ [ɔ]), and sane ~ sanity ([ej] ~ [æ]). These word pairs are assumed to be morphologically related, so both words in the pairs would have a common root: the question is what the underlying vowel of the root is. It is assumed that tense vowels undergo a process known as Vowel Shift, which rotates a tense vowel’s height one degree upward – low vowels become mid, mid vowels become high, and high vowels become low.

Another process that is relevant is Diphthongization, which inserts a glide after a tense vowel agreeing in backness with that vowel. By those rules (and a few others), /sǣn/ becomes [sējn], /serēn/ becomes [sərījn], and /divīn/ becomes [dəvajn]. By the Trisyllabic Laxing rule, when a tense vowel precedes the penultimate syllable of the word the vowel becomes lax, which prevents the vowel from shifting in height (shifting only affects tense vowels).

Accordingly, [dəvajn] and [dəvɪnətij] share the root /dəvīn/. In [dəvajn], the tense vowel diphthongizes to [dəvījn], which undergoes Vowel Shift. In /dəvīn-iti/, the vowel /ī/ instead undergoes Trisyllabic Laxing, and therefore surfaces as [ɪ].

In this way, SPE reduces the underlying vowel inventory of English to /ī/ /ū/ /ē/ /ī/ /ǣ/ /ā/ /ɔ̄/, plus the diphthong /ɔj/. Having eliminated most of the diphthongs from underlying representations, we are still left with one diphthong. In addition, there is an asymmetry in the inventory, that English has three out of four of the possible low tense vowels, lacking a front round vowel [œ̄]. It is then surmised that this gap in the system of tense vowels, and the remaining diphthong, can be explained away simultaneously, if [ɔj] derives from underlying /œ̄/. Furthermore, given the system of rules in SPE, if there were an underlying vowel /œ̄/, it would automatically become [ɔj].

Briefly, /œ̄/ undergoes diphthongization to become œ̄j because œ̄ is a front vowel and the glide inserted by diphthongization has the same backness as the preceding tense vowel. The vowel œ̄ is subject to backness readjustment which makes front low vowels [+back] before glides (by the same process, œj which derives from /ī/ by Vowel Shift becomes [ay]). Since hypothesized /œ̄/ does not become *[ø], and must remain a low vowel in order to undergo backness adjustment, Vowel Shift must not apply to /œ̄/. This is accomplished by constraining the rule to not affect a vowel whose values of backness and roundness are different.

What constitutes a valid motivation? This analysis of [ɔj] is typical of highly abstract phonological analyses advocated in early generative phonology, where little concern was given to maintaining a close relation between surface and underlying forms. The idea of deriving [ɔj] from /œ̄/ is not totally gratuitous, since it is motivated by a desire to maintain a more symmetrical system of underlying representations. But the goal of producing symmetry in underlying representations cannot be maintained at all costs, and whatever merits there are to a symmetrical, more elegant underlying representation must be balanced against the fact that abstract underlying forms are inherently difficult for a child to learn. Put simply, the decision to analyze English vowels abstractly is justified only by an esoteric philosophical consideration – symmetry – and we have no evidence that this philosophical perspective is shared by the child learning the language. If achieving symmetry in the underlying form isn’t a sufficient reason to claim that [ɔj] comes from /œ̄/, what would motivate an abstract analysis?

Abstractness can easily be justified by showing that it helps to account for phonological alternations, as we have seen in Palauan, Tonkawa, Matuumbi, Hehe, and Sanskrit. No such advantage accrues to an abstract analysis of [ɔj] in English. The only potential alternations involving [ɔj] are a few word pairs of questionable synchronic relatedness such as joint ~ juncture, point ~ puncture, ointment ~ unctuous, boil ~ bouillon, joy ~ jubilant, soil ~ sully, choice ~ choose, voice ~ vociferous, royal ~ regal. This handful of words gives no support to the abstract hypothesis. If underlying /œ̄/ were to undergo laxing, the result should be the phonetically nonexistent vowel [œ], and deriving the mixture of observed vowels [ʌ], [ʊ], [uw], [ow], or [ij] from [œ] would require rather ad hoc rules. The hypothesized underlying vowel system /īūēīǣ ɔ̄ œ̄/ runs afoul of an otherwise valid implicational relation in vowel systems across languages, that the presence of a low front rounded vowel (which is one of the more marked vowels in languages) implies the presence of nonlow front round vowels. This typological implicational principle would be violated by this abstract analysis of English, which has no underlying /y, ø/: in other words, idealizations about underlying forms can conflict.

An important aspect of the argument for [ɔj] as /œ̄/ is the issue of independent motivation for the rules that would derive [ɔj]. The argument for those rules, in particular Vowel Shift, is not ironclad. Its motivation in synchronic English hinges on alternations of the type divine ~ divinity, profound ~ profundity, but these alternations are lexically restricted and totally unproductive in English (unlike the phonological alternations in the form of the plural suffix as well as the somewhat productive voicing alternation in life ~ lives). A consequence of the decision to analyze all cases of [aj] as deriving from /ī/ is that many other abstract assumptions had to be made to explain the presence of tense vowels and diphthongs in unexpected positions (such as before the penultimate syllable).

To account for the contrast between contrite ~ contrition, where /ī/ becomes lax and t ! [ʃ], versus right ~ righteous, where there is no vowel laxing and t ! [tʃ], it was claimed that the underlying form of right is /rixt/, and rules are developed whereby /ixC/ ! [ajC]. Abstract /x/ is called on to explain the failure of Trisyllabic Laxing in the word nightingale, claimed to derive from /nixtVngǣl/. To explain the failure of Trisyllabic Laxing in words like rosary, it is assumed that the final segment is /j/ and not /i/, viz. /rɔ̄sVrj/. Other examples are that the contrast between veto (with no flapping and a secondary stress on [o]) vs. motto (with flapping and no stress on [o]) was predicted by positing different vowels – /mɔto/ vs. /vētɔ/, even though the vowel qualities are surface identical. Words such as relevance are claimed to contain an abstract nonhigh front glide, whose function is to trigger assibilation of /t/ and then delete, so relevance would derive from /relevante /, the symbol /e / representing a nonsyllabic nonhigh front vocoid (a segment not attested in any language to date).

It is not enough to just reject these analyses as being too abstract, since that circularly answers the abstractness controversy by fiat. We need to pair any such rejection with an alternative analysis that states what we do do with these words, and this reanalysis formed a significant component of post-SPE research. More importantly, we need to identify the methodological assumptions that resulted in these excessively abstract analyses. One point which emerged from this debate is that a more conservative stance on word-relatedness is called for. A core assumption in phonological analysis is that underlying representations allow related words to be derived from a unified source by rules. The concept “related word” needs to be scrutinized carefully, because liberally assuming that “related words” have common underlying forms can yield very abstract analyses.

Word-relatedness. Consider word pairs such as happy/glad, tall/long, and young/old. Such words are “related,” in having similar semantic properties, but they are not morphologically related, and no one would propose deriving happy and glad from a single underlying root. Nor would anyone propose treating such pairs as brain/brandy, pain/pantry, grain/grant as involving a single underlying root, since there is no semantic relation between members of the pair. Pairs such as five/punch are related historically, but the connection is known only to students of the history of English. The words father and paternal are related semantically and phonologically, but this does not mean that we can derive father and paternal from a common root in the grammar of English. It may be tempting to posit relations between choir and chorus, shield and shelter, or hole and hollow, but these do not represent word-formation processes of modern English grammar.

The concept of “relatedness” that matters for phonology is in terms of morphological derivation: if two words are related, they must have some morpheme in common. It is uncontroversial that words such as cook and cooked or book and books are morphologically related in a synchronic grammar: the words share common roots cook and book, via highly productive morphological processes which derive plurals of nouns and past-tense forms of verbs. An analysis of word formation which failed to capture this fact would be inadequate. The relation between tall and tallness or compute and computability is similarly undeniable. In such cases, the syntactic and semantic relations between the words are transparent and the morphological processes represented are regular and productive.

Some morphological relations are not so clear: -ment attaches to some verbs such as bereavement, achievement, detachment, deployment, payment, placement, allotment, but it is not fully productive since we don’t have *thinkment, *takement, *allowment, *intervenement, *computement, *givement. There are a number of verb/noun pairs like explain/explanation, decline/ declination, define/definition, impress/impression, confuse/confusion which involve affixation of -(Vt)-ion, but it is not fully productive as shown by the nonexistence of pairs like contain/*contanation, refine/*refination, stress/ *stression, impose/*imposion, abuse/*abusion. Since it is not totally predictable which -ion nouns exist or what their exact form is, these words may just be listed in the lexicon. If they are, there is no reason why the words could not have slightly different underlying forms.

It is thus legitimate to question whether pairs such as verbose/verbosity, profound/profundity, divine/divinity represent cases of synchronic derivation from a single root, rather than being phonologically and semantically similar pairs of words, which are nevertheless entered as separate and formally unrelated lexical items. The question of how to judge formal word-relatedness remains controversial to this day, and with it, many issues pertaining to phonological abstractness.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)