Other phenomena referring to the syllable

المؤلف:

David Odden

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

317-9

الجزء والصفحة:

317-9

16-4-2022

16-4-2022

1751

1751

Other phenomena referring to the syllable

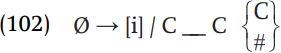

Across languages, there has been a recurring puzzle regarding the expression of natural classes via features, and the role of word boundaries. The problem is that there exist many rules which treat a consonant and a word boundary alike, but only for a specific set of rules. Many dialects of Arabic have such a rule, one of vowel epenthesis which inserts [i] after a consonant which is followed by either two consonants or one consonant and a word boundary. Thus in many dialects of Eastern Arabic, underlying /katab-t/ becomes [katabit] ‘I wrote’ and /katab-l-kum/ becomes [katabilkum] ‘he wrote to you pl’. The following rule seems to be required, in a theory which does not have recourse to the syllable.

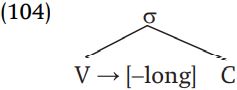

Similarly, a number of languages, such as Yawelmani, have rules shortening long vowels when followed by two consonants or by a word-final consonant (thus /taxa:k’a/ ! taxa:k ! [taxak] ‘bring!’, /do:s-hin/ [doshin] ‘report (nonfuture)’), which would be formalized as follows.

The problem is that these rules crucially depend on the brace notation (“{..., ...}”) which joins together sets of elements which have nothing in common, a notation which has generally been viewed with extreme skepticism. But what alternative is there, since we cannot deny the existence of these phenomena?

The concept of syllable provides an alternative way to account for such facts. What clusters of consonants and word-final consonants have in common is that in many languages syllables have the maximal structure CVX, therefore in /ta.xa:k/ and /do:s.hin/ where there is shortening, the long vowels have in common the fact that the long vowel is followed by a consonant – the syllable is “closed.” In contrast, in [do:.sol] ‘report (dubitative),’ no consonant follows the long vowel. Expressed in terms of syllable structure, the vowel-shortening rule of Yawelmani (and many other languages) can be expressed quite simply without requiring reference to the questionable brace notation.

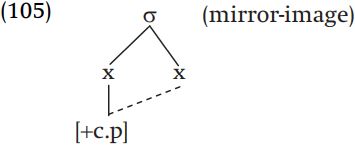

Another type of argument for the syllable is the domain argument, examples being the arguments from English glottalization and r-unrounding where the fact of being in the same syllable is a crucial condition on the rule. One example comes from Cairene Arabic, where pharyngealization spreads to all segments in the syllable (originating from some coronal sonsonant – t and t ʕ are contrastive phonemes in Arabic, likewise d and dʕ , s, and s ʕ and in some dialects r and r ʕ ). Pharyngealization also affects vowels via this pharyngealization-spreading rule. Examples of this distribution are [rʕ aʕ bʕ ] ‘Lord’ from /rʕ ab/vs. [rab] ‘it sprouted’; [tʕ i ʕ :nʕ ] ‘mud’ from /tʕ i:n]/ vs. [ti:n] ‘figs’; see especially the alternation [lʕ aʕ t ʕ i ʕ :fʕ ] ‘pleasant (m)’ ~ [lʕ aʕ t ʕ i ʕ :fa] ‘pleasant (f)’ from /lʕ atʕ i:f/. The addition of the feminine affix /-a/ has the consequence that the root-final consonant is syllable final in the masculine, but initial in the following syllable in the feminine. The rule of pharyngealization is formalized in (105).

Because of the syllabification differences between /lʕ a.tʕ i:f/ and /lʕ a.tʕ i:.fa/, f is subject to the rule only in the masculine, despite the fact that the conditioning factor, a vowel with the pharyngealization feature (derived by spreading pharyngealization from the syllable-initial consonant), is immediately adjacent to the consonant in both cases.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة