Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Common grounding

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

76-3

4-5-2022

836

Common grounding

We pointed out that discourse is potentially part of participants’ common knowledge. Indeed, it has the potential to be an important part.

All discourse is social in some way. Social actions, whether involving speech or not, do not happen randomly, but are coordinated to enable people to achieve their goals (even if the goal is simply to understand the other person). In many languages and cultures greetings may be achieved by reciprocal hand-shakes or “hellos”, or information gained by asking questions and receiving answers; both rely on common ground for their success. When you stick out your hand, say hello or ask a question, you do so with expectations about how the other person will themselves act (e.g. you expect a reciprocal hand to be proffered, a hello or answer to follow shortly). Of course, there are reflexive assumptions about these expectations: your expectations about what the other expects that you will do, and so on. Moreover, it is not just a matter of coordinating actions but coordinating understandings. Your understanding of what you meant by an action needs to be coordinated with the addressee’s understanding of what you meant by that action (and again there are reflexive assumptions about these understandings). Your agenda (a successful greeting, a successful elicitation of information) relies on common ground from which you can derive mutual expectations about the sequencing of actions, the meanings of utterances in certain contexts, and so on. Clark (1996), following Lewis (1969), notes a specific way in which this can be achieved. Behavioral conventions are part of common ground. Conventions such as a handshake, saying hello or using a questioning formula are likely to be recognized by the participants in a particular interaction (especially if they belong to the same cultures) and help co-ordinate actions and understandings.

However, as already mentioned, discourse does more than rely on common ground for its success, it can itself construct that common ground. Discourse offers the possibility of sharing knowledge, as opposed to relying on guesses about knowledge that is likely to be common (perhaps because, for example, certain socio-cultural experiences are assumed to be common). As pointed out by Brown (1995) and Lee (2001), by looking at discourse we gain some insight into how many levels of assumptions people make about common ground in practice. Somebody can present new information, as we might do with an assertion, for example, and, when it receives an acknowledgement, that somebody might reasonably believe that the target knows that information (i.e. it is old information). Moreover, the target might reasonably believe that the speaker now believes that she knows that information – the information has been assimilated into common ground – and the conversation moves on.

Jucker and Smith (1996) make a case for much of language use involving the negotiation of common ground. They point to the array of linguistic features that depend on assessments of (presumed) common ground. For example, all of the following depend on assessments of whether the speaker assumes that the target can provide or access relevant information: making an assertion as opposed to asking a question; tag questions with falling or rising intonation; definite or indefinite forms, the use of proper names or pronouns and the amount of elaboration in a noun phrase, and discourse markers such as well or in fact (Jucker and Smith 1996: 4–5). Such items are the bread and butter of common grounding. Jucker and Smith make a distinction between the implicit and explicit enhancing of common ground. When asking a question the speaker implicitly assumes that the target may be able to answer it; when using a definite noun phrase or pronoun the speaker implicitly assumes that the target will be able to identify the specific referent; when using the discourse marker in fact, the speaker implicitly assumes that what follows is inconsistent with what the target is assumed to know. But there are times when there may be much more explicit negotiation in order to, for example, establish correct reference, negotiate the meanings of key lexical items, negotiate story details or assess assumptions (ibid.: 10–15).

In the remainder, we will examine one particular kind of discourse, emergency telephone calls, which is distinguished by the fact that establishing common ground through discourse is crucial. Shared understandings of what is going on enable the operator to issue accurate advice. But there are real challenges. With telephone calls, participants are visually separated; there is only co-presence of voices. Furthermore, the operator is almost always a complete stranger to the person ringing for help. Intimates, in contrast, have a catalogue of shared experiences on which they can base assumptions. In addition, the person ringing for help is in an extreme situation and, in their distress, are sometimes not thinking through the dynamics of the communication.

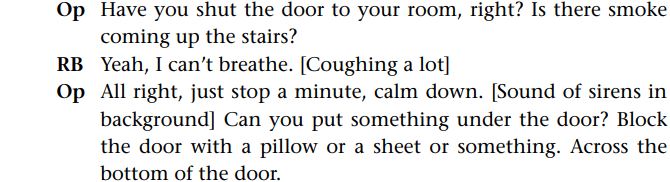

Below is a transcript of a phone call made by Rachel Barton3, in an extremely agitated state, to the emergency telephone operator, when she discovered her house was on fi re (audio was available, which enabled intonation to be checked). The transcript begins shortly after her address details have been established.

Note how the front window presupposes the existence of a front window. This is discourse-new information, but it is participant-old information. Schematic knowledge of typical housing in the UK can provide relevant elements. Houses usually have front windows. Similarly, the operator can readily assume the existence of a door for the front room (the door) and a bottom for the door (the bottom). Interestingly, she suggests the use of a pillow or a sheet, yet there has been no mention of the fact that this is a bedroom, which would typically have such items. But here again, it can be strongly assumed, on the basis of schematic knowledge about the design of UK houses, that if she is in the upstairs front room, she is in the bedroom, a room that typically contains such items. Much of the operator’s discourse seems to be designed to establish common ground with a high degree of certainty. RB’s location is crucial, so that the firefighters are directed to the right place. Hence, she repeats the discourse-old information at the front window, adding the tag right with rising intonation in order to elicit confirmation. Similarly, it is crucial to shut the door to impede the progress of the fire, hence the repetitions and confirmatory tag.

The discourse continues directly thus:

In the first turn, RB uses the proper noun Daniel. Hitherto, there has been no mention of this person nor any reason to suppose that the operator knows of his existence, this is both discourse-new and participant-new for the operator.

Yet the information appears in the guise of an existential presupposition. Of course, we should stress the fact that the addressee is Daniel, for whom the information is clearly not new. Nevertheless, the operator can infer the existence in this context of a person called Daniel. Interestingly, the operator also infers that Daniel is a little boy and specifically RB’s little boy (your little boy). We do not hear Daniel at all. It is possible that the assumption is made on the basis of schematic assumptions about family groupings, along with, possibly, gender-based schematic assumptions – Daniel denotes a male person; if there was an adult male in the room, such as a husband, they might be assumed to be participating in the emergency call.

After a few more turns, the discourse continues:

RB’s first turn here begins it, but the referent of this pronoun is not obvious. Presumably it is the smoke (it is not clear whether the window is yet open), though it could be fi re. Whichever, the lack of planning regarding what is common ground with the operator can be explained by her highly distressed state. We might compare this with the operator’s they’re on their way to you, in which the referent of they, the Fire Brigade, has been established repeatedly in the discourse and is also inferable on the basis of our schematic knowledge about fi res and emergencies in the UK, not to mention the sound of sirens, which can be heard by RB and the operator. Although we see something of the operator’s previous strategy of confirming common ground (e.g. and your little boy’s with you, with rising intonation), these turns are dominated by a different strategy. You’re all right is repeated five times (and also partially with all right), all with falling intonation. The point of the parallelism is to make salient the new and certainly controversial information, namely, that she is really all right. Similarly, we see repetition in just stop. Stop is a change-of-state verb which presupposes that RB has started to move away from the window, something that would obviously make her less accessible to the rescue efforts of the firefighters. The operator does not in fact know that this is the case, but it can be assumed on the basis of schematic knowledge about people’s reactions to danger (they move away from it) and where RB is assumed to be (i.e. close to the window) in the current context which the operator has presumably constructed in her head. RB also uses the foregrounding strategy of parallelism. The two parallel syntactic structures (two juxtaposed clauses, each with the same number of words and beginning with “I” followed by a verbal element) invite interpretation: the reason she cannot breathe is because she is asthmatic.

This analysis, then, illustrates how common ground is far from given. It is built up incrementally, partly through utterance design, but also partly through assumed background information from which various inferences can be made.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)