Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Conversational implicatures

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

93-4

6-5-2022

1447

Conversational implicatures

Grice introduced the notion of conversational implicature to refer to representations of what is implicated that arise in a principled way, namely, with reference to the Cooperative Principle, which was formulated as follows:

Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged (Grice [1975]1989: 26).

The notion of cooperation proposed by Grice was a technical one that attempted to encompass the expectations we normally have when engaging in talk about the kinds of things people will say, how they will say things, how specific we need to be, the order in which things are said, and so on. These expectations change depending on the kind of talk involved. Consequently, the notion of cooperation has to be fleshed out with reference to the activity type of the “talk exchange” in question (Mooney 2004). An activity type is essentially a culturally recognized activity such as intimate talk, family dinner table conversation, problem sharing, small talk, joke telling and so on. The Cooperative Principle should not be confused with cooperative in the folk sense of jointly engaging in an activity with a particular common purpose in mind, although it often has been, as Davies (2007) points out.

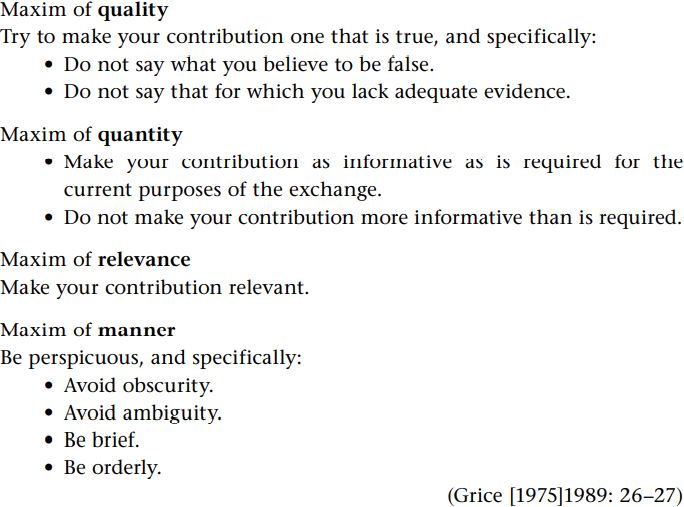

The Cooperative Principle was further elaborated through the four conversational maxims:

The idea is that the speaker makes available a conversational implicature through the expectation that he or she is observing the Cooperative Principle at a deeper level, and so not observing a specific conversational maxim in relation to the surface meaning of that utterance gives rise to a conversational implicature in maintaining that assumption. In other words, a conversational implicature arises because the speaker believes that such a meaning representation is required to make his or her utterance consistent with the Cooperative Principle.

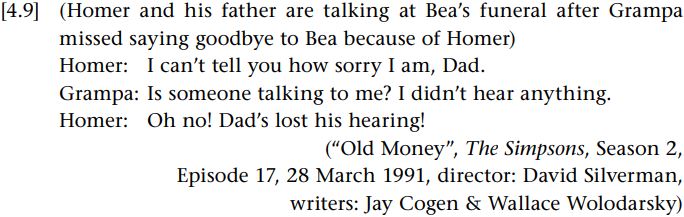

A few examples will suffice here to illustrate the general mechanism by which speakers can implicate conversational implicatures by means of exploiting (or what Grice termed “flouting”) the various conversational maxims. In [4.9], Grampa implicates that he doesn’t want to talk to Homer and that he doesn’t accept Homer’s apology by flouting the Quality1 maxim (“do not say what you believe to be false”).

It is quite evident that Grampa can hear what Homer is saying (although Homer apparently thinks otherwise). In order to maintain the supposition that Grampa is observing the Cooperative Principle, then, something must be implicated, a point that is strengthened by Grampa pointedly saying something he obviously doesn’t believe to be true. In fl outing the Quality1 maxim by pretending he can’t hear Homer’s apology, he thereby implicates that he doesn’t want to listen to Homer.

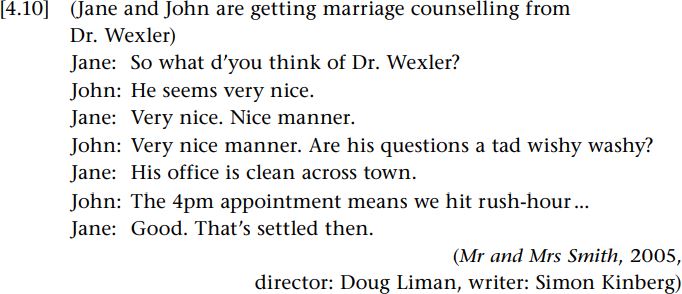

In the course of this next conversation, example [4.10], the two characters reach a consensus that it is not worth going for their appointment for marriage counselling with Dr. Wexler:

This decision is reached through a series of conversational implicatures. John and Jane both implicate that Dr. Wexler is boring or unhelpful (and thus sessions with him are boring and unhelpful) by fl outing the Quantity1 maxim (“make your contribution as informative as required”), since saying a professional counsellor is “nice” and has a “nice manner” is clearly not very informative. In order to maintain the supposition that John and Jane are observing the Cooperative

Principle, then, something else must be implicated here. What isn’t said here is that Dr. Wexler is interesting or helpful (i.e. characteristics of a “good” counsellor), which leads us to what is implicated, namely, that Dr. Wexler is uninteresting and unhelpful, and thus so are their sessions with him. They then invoke the Relevance maxim (“make your contribution relevant”) to implicate that there are other reasons for not going to the appointment, including the fact that it is a long way to his office from their home, and that they would have to drive through very busy traffic to make it in time for the appointment. While it is never said (cf. “Good. That’s settled then”), it is clear by the end of the conversation that they have decided to miss their appointment.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)