Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Pragmatic acts in sequence

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

185-6

17-5-2022

1131

Pragmatic acts in sequence

We noted that the processing of pragmatic meanings progresses incrementally (within utterances and turns) and sequentially (across utterances and turns). The very same principles apply to the way in which pragmatic acts are produced and interpreted in interaction. Incrementality with respect to pragmatic acts refers to the way in which speaker’s adjust or modify their talk in light of how the progressive uttering of units of talk is received by other participants. Sequentiality, on the other hand, refers to the way in which current turns or utterances are always understood relative to prior and subsequent talk, particularly talk that is contiguous (immediately prior or subsequent to the current utterance or turn). The fundamentally sequential organization of pragmatic acts means that “next turns provide evidence of the understandings of recipients of prior turns” (Heritage 1984b: 260). It follows from this that participants can use next turns as a resource in producing their own talk and in interpreting the talk of others (as well as in interpreting how others interpret their talk). It also means that we, as analysts, have access to a record of “publicly displayed and continuously up-dated intersubjective understandings” (ibid.: 259) when examining pragmatic acts in interaction. It is very important to remember, however, that this is an indirect record from which both participants and analysts can only make inferences. Our reliance on inferences in interpreting pragmatic acts is the source of their indeterminacy in many situations, just as is the case in the processing of pragmatic meaning in many instances.

Let us consider the case of invitations. In speech act theory, the key felicity conditions include that the proposed action encompassed by the invitation is of benefit to the addressee (preparatory), the addressee is (theoretically) able and willing to accept (preparatory), the speaker’s psychological state is apposite (they sincerely wish to offer hospitality, etc.) (sincerity), and the utterance counts as an offer of hospitality (essential). The key components of an invitation are generally said to include some kind of availability checking (pre-invitation), the invitation head act (e.g. would you like to ... ?, do you want to ... ?), and supportive moves, including grounders and reconfirmations. However, if we consider invitations from the perspective of pragmatic act schema theory and examine them in their sequential environment, we find there is a much more nuanced and complex story to tell.

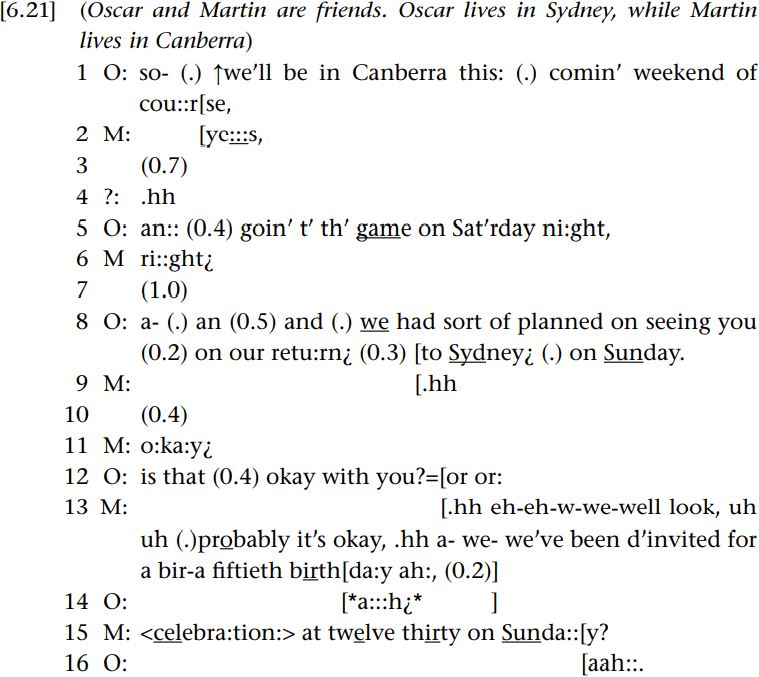

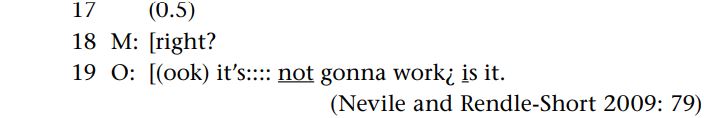

Consider the following interaction between two friends, where Oscar has called Martin to talk about his forthcoming visit to Canberra.

Regarding Oscar’s emerging proposal, one thing we can note initially is that Oscar frames his opening of the sequence as reiterating something that they both already know, namely, that Oscar and his family will be going to Canberra that coming weekend. In other words, the use of of course in turn 1 presents this as information that is not new to the participants. Oscar goes on to outline his plan to go to watch a sports game, one which they are both aware of, which is evident from his use of the definite article here. This plan is prefaced with and, which indicates that this utterance (turn 5) is linked to his prior talk in turn 1 as “part of a bigger project” (Heritage and Sorjonen 1994), in this case, a proposal to visit Martin, which becomes evident in Oscar’s subsequent utterance in turn 8. The self-invitation itself is formulated as a tentative or hedged plan in turn 8 (sort of planned). Oscar’s projected expectations about whether this proposal will be accepted or not are further downgraded by the trailing-off disjunctive (or or) in turn 12, which opens up interactional space for a declination through implicature (i.e. implying either “or not” or “or [something else]”). What is important to note about the production of this proposal is that each increment of it (in turns 1, 5, 8 and 12) follows minimal responses from Martin (i.e. yes, right, okay in turns 2, 6 and 11), as well as relatively lengthy pauses (in turns 3, 7 and possibly 10). These responses prompt Oscar to continue his talk, but show no commitment to the underlying agenda that Martin is likely to have realized right from the beginning, when Oscar brings up his forthcoming trip to Canberra. Oscar’s formulation of the components of this proposal are thus influenced by the responses from Martin, being adjusted and perhaps re-ordered in light of what Martin says (and indeed does not say, namely, pre-emptively inviting Oscar and his family to come to visit).

Now let us consider Oscar’s realization that his proposal is being declined. A display of such an understanding emerges progressively over the course of this sequence. It is evident in part from the tentative nature of the proposal Oscar makes (turn 8), and the provision of an “out” for Martin through implicating that such a visit might not be okay (turn 12). It is also shaped by Martin’s earlier minimal responses, as well as the way in which he frames his subsequent response to the proposal in turns 13 and 15. Martin’s response is framed with a number of markers, including an audible in-breath (that indicates a lengthy response is likely to follow), hesitation and restarts, and well-prefacing (a common marker of dispreferred responses), thereby framing his response as dispreferred (in the CA sense of responses that are marked as delayed or non-straightforward). While he offers qualified acceptance (probably it’s okay), the preceding markers of a dispreferred response, together with the subsequent account for that qualification (i.e. that Martin has to attend another – important – event, i.e. a 50th birthday celebration), and guide Oscar to infer that his proposed visit is not feasible. That Oscar makes this inference is evident from the occurrence of the pragmatic marker ah that receipts new information in turn 16 (Heritage 1984a) (a point we will discuss further), as well as making explicit what he has inferred through his formulation in turn 19. What is important to note is that Oscar’s inference is not only influenced by what Martin says here in response, but also by the surrounding sequence where Martin does not offer a pre-emptive invitation despite having multiple opportunities to do so; Oscar thus does not end up ‘soliciting’ an invitation from Martin despite his tentatively framed proposal.

It is evident from our analysis of the way in which Oscar’s proposal develops incrementally and the way in which Martin’s responses shape the overall trajectory of the sequence (i.e. the overall structure and the individual components of the proposal) that this sequence emerges as a joint effort on the part of both Oscar and Martin.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)