Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Impoliteness

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

222-7

26-5-2022

1181

Impoliteness

Although the study of impoliteness has a fairly long history (usually in the guise of the study of swearing), and although early scientific attempts to address the topic (e.g. Lachenicht 1980) did not galvanize scholars, momentum has been increasing, with the arrival of Lakoff (1989), Culpeper (1996), Tracy and Tracy (1998), Mills (2003), Bousfield (2008), Bousfield and Locher (2008) and Culpeper (2011a), to mention but a few. A key question is: should a model of politeness account for impoliteness using the same concepts, perhaps with an opposite orientation, or is a completely different model required? Impoliteness phenomena are not unrelated to politeness phenomena. One way in which the degree of impoliteness varies is according to the degree of politeness expected: if somebody told their University Vice-Chancellor to be quiet, most likely considerably more offence would be taken than if they told one of their young children to do the same. Moreover, the fact that sarcasm trades off politeness is further evidence of this relationship. For example, thank you (with exaggerated prosody) uttered by somebody to whom

a great disfavor has been done, reminds hearers of the distance between favors that normally receive polite thanks and the disfavor in this instance. There are, however, also some important differences between politeness and impoliteness. Recollect that both of the relational frameworks. Accommodate, explicitly or implicitly, both politeness and impoliteness. It is true that within a relational approach such as Locher and Watts (2005) there is a ready opposition: impoliteness can be associated with a negative evaluation as opposed to a positive evaluation, which can be aligned with politeness. However, the categories “positive” and “negative” are very broad. When we look at the specifics, the polite/impolite opposition runs into some difficulties.

One possible characteristic of politeness, is consideration. In a very broad sense any impoliteness involves being inconsiderate, but defining something in terms of a negative (i.e. what it is not) is not very informative about what it actually is. Moreover, Culpeper (2011a) reports a study of 100 impoliteness events narrated by British undergraduates. 133 of the total of 200 descriptive labels that informants supplied for those events fell into six groups (in order of predominance): patronizing, inconsiderate, rude, aggressive, inappropriate and hurtful. Clearly, being inconsiderate is a descriptive label that strikes a chord with participants. However, patronizing, by far the most frequent label, does not have a ready opposite concept in politeness theory. Presumably, it relates to an abuse of power, a lack of deference, but neither power nor deference are well described in the classic politeness theories. Similarly, aggressive, with overtones of violence and power, has only a very general opposite in politeness theory, namely, harmonious. And there are yet other differences or cases where there do not appear to be easy diametric opposites between impoliteness and politeness. Anger is one of the most frequent emotional reactions associated with impoliteness, particularly when a social norm or right is perceived to have been infringed. But anger lacks a similarly specific emotional opposite associated with politeness. Furthermore, taboo lexical items appear relatively frequently in impolite language. Lexical euphemisms, however, while they are associated with politeness, play a minor role.4

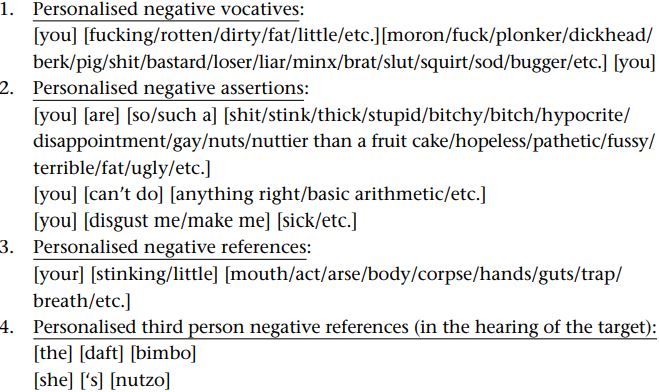

An important point is that relational frameworks are not models of politeness or impoliteness themselves; they are models of interpersonal relations which may accommodate at least some aspects of politeness, impoliteness, and so on. So, while they will provide insights, we cannot expect a complete apparatus for accommodating or explaining the rich array of communicative action undertaken to achieve and/or perceived by participants as achieving impoliteness (see, for example, the descriptions in Culpeper 1996; Bousfield 2008). One obvious difference between politeness and impoliteness is that impoliteness has its own set of conventionalized impolite formulae. We understand conventionalization here in the same way as Terkourafi (e.g. 2003), namely, items conventionalized for a particular context of use. As we saw, for such items to count as polite, they must go unchallenged (e.g. Terkourafi 2005a; see also Haugh 2007b, for a related point). Conversely, then, a characteristic of conventionally impolite formulae is that they are challenged. In Culpeper’s (2011a) data, by far the most frequent impolite formulae type is insults. These fall into the following four groups (all examples are taken from naturally occurring data; square brackets give an indication of structural slots, which are optional to varying degrees, and slashes separate examples):

Apart from insults, other important impoliteness formulae types are: pointed criticisms/complaints; challenging or unpalatable questions and/or presuppositions; condescensions; message enforcers; dismissals; silencers; threats; curses and ill-wishes; non-supportive intrusions (further detail and exemplification can be found in Culpeper 2011a).

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)