Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Metapragmatics and reflexivity

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

237-8

27-5-2022

1473

Metapragmatics and reflexivity

The prefix meta, which comes from the Greek μετά meaning “above”, “beyond” or “among”, is normally used in English to indicate a concept or term that is about another concept or term. For example, metadata is data about data, meta-language is language about language, while metapragmatics refers to the use of language about the use of language. In order for participants to talk about their use of language they must, of course, have some degree of awareness about how we use language to interact and communicate with others. This type of awareness is of a very particular type, however, in that it is almost inevitably reflexive. What this means is that awareness of a particular interpretation on the part of one participant, for instance, is more often than not interdependently related to the awareness of interpretations (implicitly) demonstrated by other participants. In other words, in using language to interact or communicate with others, participants must inevitably think about what others are thinking, as well as very often thinking about what others think they are thinking, and so on. And not only do participants engage in such reflexive thinking in using language, they are also aware of this reflexivity in their thinking, albeit to varying degrees. We can thus observe various indicators of such reflexive awareness in ordinary language use.

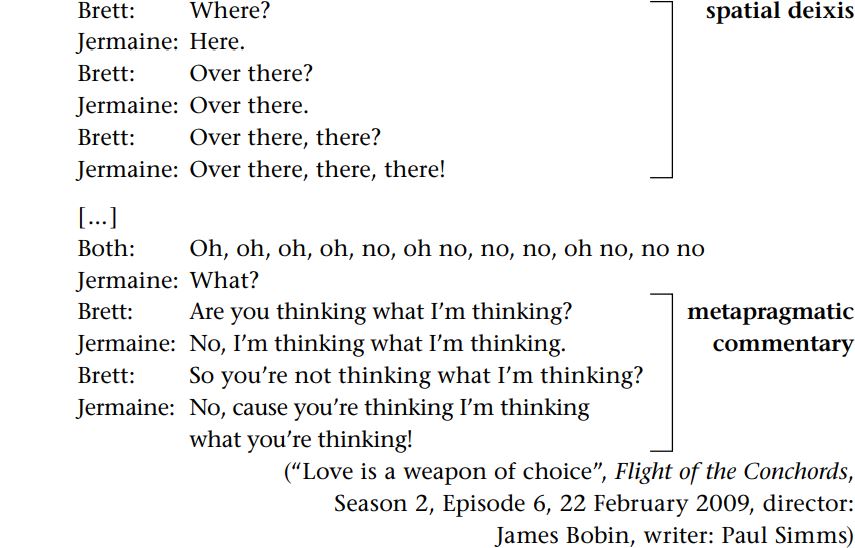

Consider, for instance, the following excerpt from an episode of the HBO comedy, Flight of the Conchords. The two characters, Brett and Jermaine, have just met a lady in the park who was looking for her lost dog. They start singing a song, at the conclusion of which they realize they are singing about the very same lady they have just met. Much of the song involves a back and forth between the two characters as they attempt to establish who they are referring to:

In the course of this excerpt Brett and Jermaine attempt to establish the real world. They begin by attempting to establish the time they met (temporal deixis), then move to discussing where they met her (spatial deixis). Eventually, they start to realize they might be singing about the same girl. This metapragmatic discussion breaks down, however, when Brett’s suggestion that they might be referring to the same girl (Are you thinking what I am thinking?) is treated literally by Jermaine. What happens here is that while Brett implies that they are talking about the same girl, Jermaine only responds to what is said by Brett (that Brett is thinking what Jermaine is thinking). In that sense, Jermaine’s response to the reformulation of the question by Brett is strictly speaking correct (No, cause you’re thinking I’m thinking what you’re thinking). However, since it is a very complex utterance – about Jermaine’s belief about Brett’s belief about Jermaine’s thought in relation to Brett’s thought – it becomes almost impossible to follow in the context of the song. Nevertheless, while up until this point in the song they have not yet successfully established the referent in question, it is clear that they are reflexively aware of the other’s use of language and, moreover, that this reflexive awareness enters into the language they use in the form of explicit metapragmatic commentary.

Such reflexive awareness does not, however, always surface so explicitly in language use. As Niedzielski and Preston (2009) point out, participants may not always be able to articulate their reflexive understandings of language use, despite such understandings being inherent in that very same usage. It is also apparent that such awareness may be more or less salient across different situated contexts. Thus, while metapragmatics often involves the study of instances where participants attend to communication, that is, where language is used to “evoke some kind of communicative disturbance” (Hübler and Bublitz 2007: 7) or “to intervene in ongoing discourse” (ibid.: 1), it is not restricted to instances that are explicitly recognized by participants, as we shall see in the remainder.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)