Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Morphology: the study of word structure

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

107-6

2023-12-18

1865

Morphology: the study of word structure

Derivational morphology is concerned with the creation of new words.

Inflectional morphology involves the marking of grammatical categories (for example number, tense or gender).

The distinction between morphology and syntax as sketched above would seem to presuppose a clear definition of the term word but, as we shall see, ‘words’ prove problematical on a number of levels. If asked ‘how many words there on this page?’, we’d probably count the number of items with blank spaces either side (would contractions like that ‘we’d’ in the previous clause count as one word or two?) and ignore the fact that some words (e.g. ‘the’) are used more than once. But if asked instead how many words there are in the Oxford English Dictionary, or how many words of Spanish we know, our criteria would change: ‘words’ in this case would imply different words as cited independently in the dictionary, and would not include inflected forms predictable by rule, i.e. we would treat dog/dogs or read/reads/reading as the same ‘word’ in each case. i.e. dog+s dogs, or read+ing reading.

For word in this second sense, linguists generally use the term lexeme, and the scope of lexemes includes items made up of more than one word (e.g. set up; windscreen wiper), and even idioms like to penny pinch, to keep tabs on, where the meaning cannot be broken down into the component parts. Where the distinction is important, by convention linguists use small capitals to refer to lexemes, so READ refers to the verb to read and all its inflected forms.

To add yet a further complication, words can have more than one function: in a sentence like ‘He is thinking about Mary’ the word thinking is a verbal participle, indicating an action which is ongoing; in ‘Bill was overly fond of thinking’ the same form is a gerund, i.e. it functions as a noun (we could substitute, for example, ‘football’ or ‘jam’ for ‘thinking’ and the sentence would remain grammatical). Here we need to distinguish a third sense of word, i.e. a grammatical or morphosyntactic word.

Even allowing for these qualifications, deciding what counts as a ‘word’ and what does not proves surprisingly tricky. The definition we routinely apply in everyday life, namely calling something a ‘word’ if it is separated by orthographical spaces on the page, is unsatisfactory on a number of counts. Firstly, this seems an arbitrary basis for definition in the absence of pre-existing criteria for separation: these ‘gaps’ do not after all correspond to pauses or breaks that are actually made in speech (if they did, there would be no need for the comma I’ve just used to indicate that a pause should be made, nor for the full stop with which this sentence will end). Secondly, only a minority of present and past languages have a writing system in any case, so in most instances we have no orthographic conventions to help us.

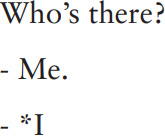

One criterion offered by Bloomfield is that a word should be a minimal free form: John, houses, riding, hopeless, for example, all qualify as ‘words’ because they could occur as one-word answers to a question (‘What are you doing?’ – ‘Riding’; ‘How’s your arithmetic?’ – ‘Hopeless!’). But this poses problems because some items which we would probably like to think of as words fail this criterion. In English, these would include ‘functional’ items such as the articles a and the, or the subject pronouns:

More awkward still from this point of view is French, which requires nouns to have articles, so for example ‘I want bread’ is ‘Je veux du pain’: on the minimal free-form criterion not only pain (bread) but almost all nouns would be ruled out. A more promising criterion is separability: the dog should be seen as a sequence of two words because adjectives, for example, can be interspersed between them, e.g. the great big lovable old dog. But this criterion proves no more watertight: broad beans, for example, looks like two words because broad and beans can both occur independently in other contexts (it’s as broad as it’s long; ‘Mum! I managed to sell the cow for some magic beans!’), but we cannot separate the two elements (*broad big beans; ?how broad are your beans?1 ), suggesting that they form a single lexical unit.

Furthermore, in informal language, we do encounter interspersed elements at points where there is clearly no word boundary (abso-bloody-lutely!). A final criterion might be stress: blackbird, for example, is one word rather than two because, unlike black bird, it carries only one main stress. This will work for a whole range of items, including thorough, achieve, resist, but would rule out a number of items which would not normally bear stress, for example a, the, he, it, and so on, and in any case, not all languages have word-level stress: stress in French for example is borne by the last syllable of the rhythm group, which may consist of several ‘words’ on other criteria.

The criterion of ‘potential pause’ has even been advanced, unconvincingly, to align linguistic and orthographical word criteria: while we do not normally pause between words, we could – potentially – do so (as I’ve attempted to indicate here by dashes). But this criterion soon proved to be an impostor: how can we distinguish a hesitation in mid-word from a pause at a word boundary? Only, of course, by knowing in advance where the word boundaries are, in which case the definition becomes circular.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)