Southeastern phonology: consonants P, T, K

المؤلف:

Ulrike Altendorf and Dominic Watt

المؤلف:

Ulrike Altendorf and Dominic Watt

المصدر:

A Handbook Of Varieties Of English Phonology

المصدر:

A Handbook Of Varieties Of English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

192-9

الجزء والصفحة:

192-9

2024-03-07

2024-03-07

1293

1293

Southeastern phonology: consonants

P, T, K

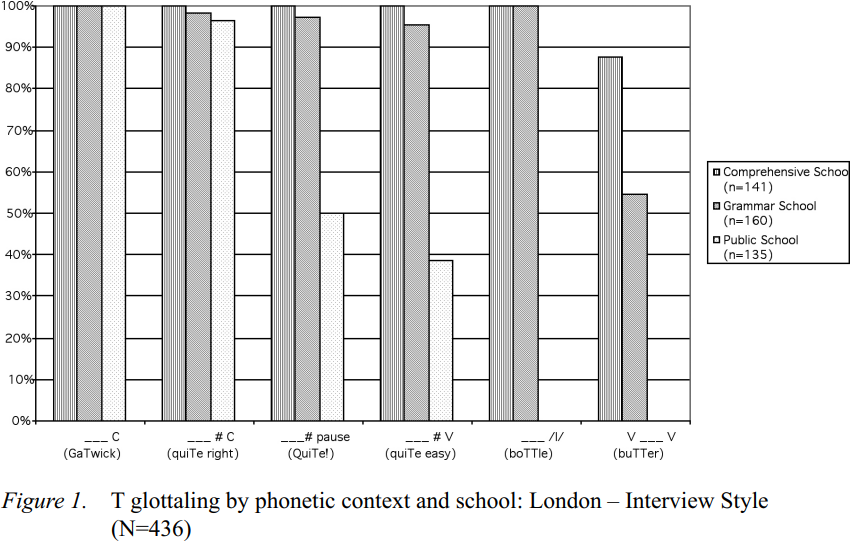

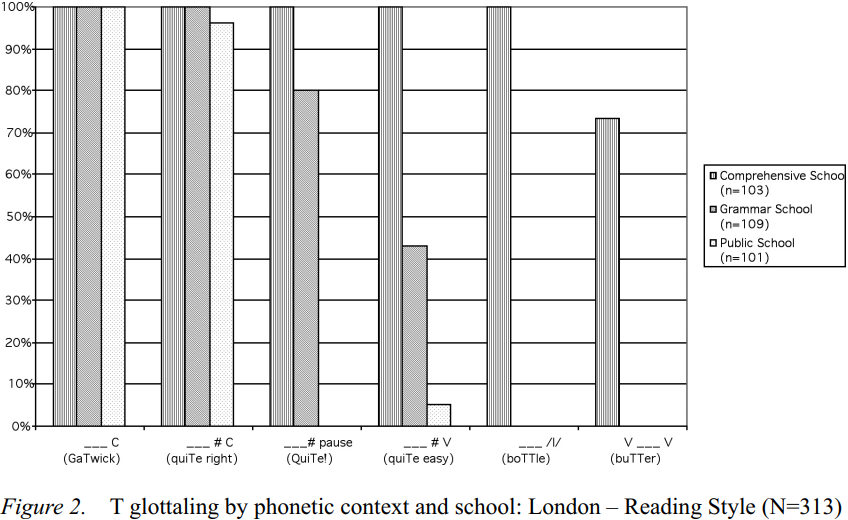

Pre-glottalization and glottal replacement of syllable-final /t/ and (to a lesser extent) /p/ and /k/ are very common in London and the Southeast. Despite its wide geographical dissemination, T glottalling has a tradition of being regarded as a stereotype of London English. Its current spread (at least in the Southeast) is equally ascribed to the “influence of London English, where it is indeed very common” (Wells 1982: 323). In recent years, glottalling – and in particular T glottalling – has increased dramatically in all social classes, styles and phonetic contexts. Social differentiation is, however, retained by differences in frequency and distribution of the glottal variant in different phonetic contexts. The result of this interplay can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, taken from Altendorf (2003). These data show the frequency of T glottaling in two styles of speech produced by schoolchildren drawn from three school types (comprehensive, grammar, and public) and demonstrate marked contextual effects for some speaker groups.

Phonetic constraints affect the occurrence and frequency of the glottal variant in the following order: pre-consonantal position (Scotland, quite nice) > pre-vocalic across word boundaries (quite easy) and pre-pausal position (Quite!) > word-internal pre-lateral position (bottle) > word-internal intervocalic position (butter). Their effect is further enhanced by social and stylistic factors:

(1) Middle-class speakers differ from working-class speakers by avoiding the glottal variant in socially sensitive positions when speaking in more formal styles. They reduce the frequency of the glottal variant in pre-pausal and prevocalic positions (as in Quite! and quite easy), and avoid it completely in the most stigmatized word-internal intervocalic position (as in butter).

(2) Upper-middle-class speakers differ from all other social classes in that they avoid the glottal variant in these socially sensitive positions in both styles. They have a markedly lower frequency of pre-pausal and pre-vocalic T glottaling in the most informal style and avoid it almost completely in the more formal reading style. T glottaling in the most stigmatized positions, in pre-lateral and intervocalic position (as in bottle and butter), does not occur at all for these speakers.

The results for the London upper middle class reported by Altendorf (2003) confirm those of Fabricius (2000). In the results for her young RP speakers, there is no intervocalic T glottaling in any style, and no pre-pausal or pre-vocalic T glottaling in the more formal style. Fabricius also shows that the effect of phonetic context and style is highly significant.

Examination of the result for environment using the Newman Keuls test for pairwise comparison showed that the consonantal environment was significantly different from the pre-vocalic and the pre-pausal environments (p<0.02). The prevocalic and prepausal results were not significantly different from each other. (Fabricius 2000: 140)

It is also interesting to note that T glottaling displays regional variation within Fabricius’ group of RP speakers.

Pre-consonantal glottalling can reasonably be regarded as the ‘first wave’ of glottalling. The ‘second wave’ seems to be the prepausal category, which shows a significant difference between the Southeastern category and the ‘rest of England’ category. As we have seen, London and the Home Counties pattern together on this feature, while the rest of England lags behind. The ‘newest’ wave of glottalling is evident in the pre-vocalic category, where the London-raised public school speakers use pre-vocalic t-glottalling at a significantly higher rate than speakers from other parts of England in less formal styles of speech. (Fabricius 2000: 134)

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة