Monophthongs

المؤلف:

Magnus Huber

المؤلف:

Magnus Huber

المصدر:

A Handbook Of Varieties Of English Phonology

المصدر:

A Handbook Of Varieties Of English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

849-47

الجزء والصفحة:

849-47

2024-05-10

2024-05-10

2251

2251

Monophthongs

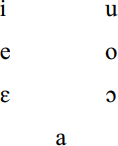

The 12 RP monophthongal vowels are reduced to 5 in the system of the most “Ghanaian” speakers, i.e. those whose English shows all possible mergers or substitutions of the BrE monophthong system. These vowels are /i, ε, a, ɔ, u/. To these are added the half-close /e/ and /o/, which result from the monophthongization of the BrE diphthongs /eɪ/ and /ou/, so that in total there are 7 GhE monophthongs, a system shared with the other West African Englishes:

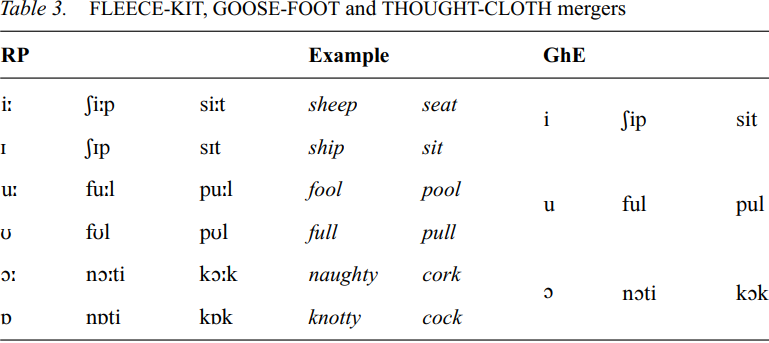

Some of the simplifications of the monophthong system result from the tendency in GhE to neutralize length distinctions present in RP, resulting in homophony of RP minimal pairs. There are three such mergers of RP vowel oppositions:

This process, a pan-African feature of English (Simo Bobda 2000a: 254), tends to occur in the GhE renderings of the RP pairs /i:-ɪ/ , /u:-ʊ/, and /ɔ:-ɒ/ , i.e. pairs whose second members show a more open (and laxer) realization than the first. That vowel length tends not to be distinctive in such GhE pairs is interesting, since length is a phonological feature in some indigenous languages like the large Akan group or Hausa, which has some currency in the country.

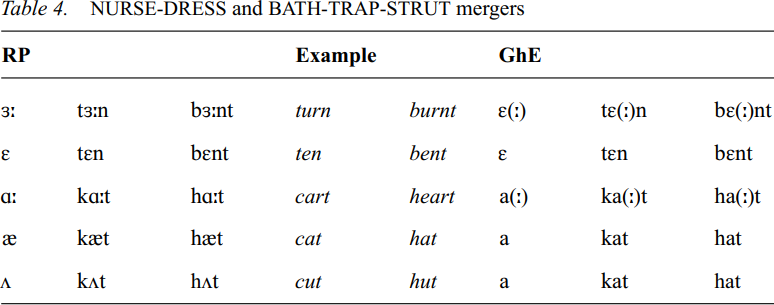

There are two other vowel mergers that often result in GhE homophony. These result from a fusion of RP /з:/-/ε/ and /ɑ:/-/æ/- /Λ/ , vowels not primarily distinguished by degree of openness (laxness). However, RP length differences are more regularly – though not categorically – maintained here:

Most West African languages do not have central vowel phonemes. Speakers of West African English accordingly replace RP /ə, з:, Λ/ by front or back vowels. On the other hand, /a/ – very close to the English low back vowel – is found in many languages and heard in the names Ga, Akan, Dagaari, Dagbani, but does not surface GhE.

The almost categorical substitution of the front vowel /ε/ for RP /з:/ in all contexts is one of the main characteristics that sets GhE apart from other West African Englishes. The latter mainly replace the central vowel by /a/ and /ɔ/ and only in a limited and predictable number of cases by /ε/ (Simo Bobda 2000b: 190). The cause of the substitution of RP /з:/ by GhE /ε/ is often attributed to L1 influence. Like the other West African languages, the majority of Ghanaian languages lack the central vowel /з:/: in my estimate, based on an examination of the vowel systems of 29 indigenous Ghanaian languages, representing about 87% of Ghana's population, some 14% of Ghanaians are familiar with central vowels. This includes speakers of Ewe, spoken by about 10% of the population – by far the largest Ghanaian language with a central vowel (i.e. [ə]). Note, however, that in all except a couple of very small languages (spoken by a total of about 1% of the population), central vowels are either allophonic variants of front or back vowels, or are heavily restricted in their occurrence. The largest Ghanaian languages, Akan and the Ga-Dangme cluster (the mother tongues of 50% of Ghanaians), do not have central vowels, which may be the reason why RP /ə, з:, Λ/ are largely avoided in GhE. While central vowels are absent from the majority of indigenous languages, most have /ε/. Sey (1973: 147) maintains that for the Ghanaian speaker of English "the two vowels [ε and з:] are sufficiently alike to be confused with each other". Although I cannot at present offer a better explanation for the phenomenon, Sey's scenario does not account for the whole story, since it leaves unanswered the question why in the English of countries like Nigeria, whose indigenous languages similarly lack central vowels but have /ε/ (observation based on an analysis of 28 Nigerian languages), /з:/ is mostly replaced by /a/ and /ɔ/ – not by /ε/. Colonial input varieties of English may have played a role in the establishment of different correspondences of RP /з:/ in the various West African Englishes.

The /ɑ:-æ-Λ/ merger seems to be due to L1 transfer, since none of the main Ghanaian languages has all three vowels. Ghana shares the lowering of the TRAP vowel with most other West African Englishes except Liberian English (Simo Bobda 2003: 21). In fact, the replacement of /æ/ by /a/ is a feature found in all African Englishes, east, west, and south (Simo Bobda 2000a: 254). However, it is in the substitution of RP /Λ/ that contemporary GhE clearly distinguishes itself from other West African Englishes. While the latter render RP /Λ/ as /ɔ/ , today's GhE varies between /ɔ/ and (perhaps more often) /a/. In some cases, /Λ/ is replaced by /ε/.

To start with /ε/, Sey (1973: 147) notes that "the /Λ/ > /ε(:)/ pronunciation is common in the Cape Coast area". This is the region of Ghana that first saw British territorial colonization (territorial expansion going back to the early 19th century), that has had the longest tradition of English-medium schools, and that was the capital until 1877. The indigenous language in and around Cape Coast is Fante (an Akan dialect), and Gyasi (1991: 27) accordingly associates the /ε/ pronunciation with Fantes. That RP /Λ/ > GhE /ε/ has long been firmly established in the Cape Coast area is illustrated by a remark by the missionary Dennis Kemp, who worked in Cape Coast from 1887 to 1896:

A somewhat amusing little accident occurred at the annual school examination. Our scholars, for some inexplicable reason, invariably pronounce the letter “u” as “e,” and will insist, for example, in calling “butter” “better.” The senior scholars were asked to name the principal seaports of England. One little lad thought of “Hull.” But in consequence of the difficulty just mentioned the examiner did not recognize the name, and somewhat absent-mindedly asked in which part of England “Hell” was. (Kemp 1898: 179)

Simo Bobda (2000b: 189) says that today /Λ/ > /ε/ cuts "across all ethnic groups in Ghana" and that its occurrence is lexically or idiolectally conditioned. My own recordings of GhE corroborate this: there is a lot of variation, but /ε/ seems indeed to be lexically conditioned. It occurs most regularly in function words like but, us, just, such, and much, but also in a small number of high-frequency lexical items such as month. However, it seems that even in the speech of non-Fantes, /Λ/ > /ε/ replacement is not a particularly new phenomenon: even the oldest speakers, born in the early 1900s and from different ethnic backgrounds, show this characteristic. It must already have been established and widespread in pre-WW I GhE. This does not mean that /Λ/ > /ε/ replacement did not originate with the Fantes: from the earliest colonial days, Cape Coast was the educational centre of the Gold Coast and continues to be an important school and university city today. It was an important teacher training centre and Fante teachers may well have carried the /ε/ pronunciation to other parts of the colony in the late 1800s.

As mentioned above, the much more frequent substitution of RP /Λ/ today is /ɔ/ or /a/, the latter distinguishing GhE from most of the other WafEs. GhE shares /Λ/ > /a/ with the Hausa English of Northern Nigeria, but the latter appears to be changing towards the dominant Yoruba pronunciation /ɔ/ (Simo Bobda 2000b: 188). Today, /ɔ/ and /a/ are in free variation in GhE. One and the same individual may pronounce the tonic vowels in e.g. country, culture, or much as [ɔ] or [a]. Personal observation suggests that with some speakers, this variability is simply due to linguistic insecurity since both forms are current in GhE today. Simo Bobda (2000b: 187–188) proposes that /ɔ/ may occur only if certain conditions concerning spelling, assimilation, ethnicity of the speaker, and age are met. However, my data suggests that these factors only partially account for the occurrence of /ɔ/ or /a/. I will illustrate this by speakers A and B in the conversation accompanying this article.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة