TRANSFORMATIONAL COMPONENT

المؤلف:

HOWARD MACLAY

المؤلف:

HOWARD MACLAY

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

174-13

الجزء والصفحة:

174-13

2024-07-18

2024-07-18

1286

1286

TRANSFORMATIONAL COMPONENT

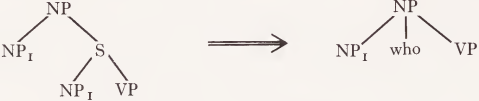

This component takes as input the deep structures generated by the base component and applies singulary transformations to them to produce the set of surface structures. Suppose we have a relative transformation which has the following effect:

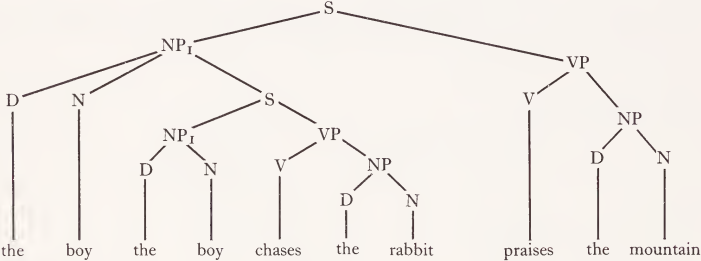

Given the following deep structure:

the relative transformation, in effect, substitutes ‘ who ’ for the second occurrence of ‘ the boy ’ producing The boy who chases the rabbit praises the mountain. Thus, complex sentences are formed in a way quite different from the operations of GT-1. A deep structure may be affected by a series of transformations which apply, in order, to the lowest sentence of the tree, then to the next lowest and so on until the highest S has been reached. A more realistic base component would also include other instances of S on the right hand side of rules (i.e. in a rule such as VP - - > VB (verbal) + (NP) + (S)) which greatly increases the power and flexibility of the system. The transformational rules act as a ‘ filter ’ in that they will block many of the structures generated by the base. For example, had the second noun phrase above been the girl the relative transformation could not have been applied. The semantic component must also be able to block deep structures that have no readings. The status of semantics as a proper part of a linguistic description had been anticipated by GT-1. During GT-2 it becomes something more than a poor relation of syntax and something less than a full-fledged partner. It seems obvious in retrospect that the systematic introduction of semantics by Katz and Fodor put various pressures on the syntactic component which were important in inducing the great changes that can be seen when Aspects of the Theory of Syntax is compared to Syntactic Structures.

Phrase structure rules are redefined, one of the two major types of transformations (generalized) is dropped and a syntactic feature analysis (based on the feature analyses of phonology and semantics) is introduced. It is notable that although the need to view transformations as not affecting meaning arose initially from Katz and Fodor’s work in semantics the requirements of the semantic component were not sufficient to justify such a change without independent syntactic motivation. Katz and Postal devote the major portion of their book to a demonstration that the apparent counter-examples to their proposal (that singulary transformations don’t change meaning and generalized transformations play only a minor role) may be rejected on purely syntactic grounds. Presumably, if they had failed to show this, their proposal would not have been acceptable regardless of the simplifications it would have introduced to the semantic component. This attitude is clearly shown in Chomsky’s comments on their work:

This principle obviously simplifies very considerably the theory of the semantic component as this was presented in Katz and Fodor (‘ The structure of a semantic theory ’). It is therefore important to observe that there is no question-begging in the Katz-Postal argument. That is, the justification for the principle is not that it simplifies semantic theory, but rather that in each case in which it was apparently violated, syntactic arguments can be produced to show that the analysis was in error on internal, syntactic grounds. In the light of this observation, it is reasonable to formulate the principle tentatively as a general property of grammar. (Chomsky, 1966, p. 37)

One is entitled to suppose that had some dramatic syntactic simplification (such as the introduction of syntactic features in GT-2) been shown to be without semantic justification or even to complicate semantic analysis so much the worse for semantics. This is, of course, not really a case of random prejudice against meaning. Syntax was a very well developed field of study and there seemed no reason to pay much attention to the needs of a badly undernourished semantic component. All of the linguists mentioned here were in essential agreement on this point. Chomsky comments in this volume on the lack of necessary directionality in grammars of the GT-2 type which ‘generates quadruples (P, s, d, S) (P a phonetic representation, s a surface structure, d a deep structure, S a semantic representation). It is meaningless to ask whether it does so by “first” generating d, then mapping it into S (on one side) and onto s and then P (on the other).’ Nonetheless it cannot be entirely accidental that all known formulations of GT-2 grammars present S (using Chomsky’s terminology) as the output of a dependent component whose operation depends on having d as input. The term interpretive applied to the semantic component suggests its secondary status. Thus, whatever the ultimate logical status of the relationships between the components of a grammar may be, it seems evident that for grammars of the GT-2 type, syntax is not only independent of meaning but prior to it both psychologically and operationally. The semantic component is assigned those tasks which cannot be conveniently accomplished syntactically. This is no doubt a carry over from earlier stages where the lack of a semantic component made it necessary to handle many semantic issues syntactically. An instance of this is found in the selection features of the lexicon which will provide a point of attack for the linguists of GT-3B.

To summarize the status of GT-2 grammars in terms of Table 1: meaning is now an official part of a linguistic description, syntax is independent and divided into deep and surface structures with the former providing the exclusive basis for semantic interpretation. The general goal of a linguistic description is to state the relationships between sound and meaning.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة