Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

GT-3

المؤلف:

HOWARD MACLAY

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

176-13

2024-07-19

1392

GT-3

All of the papers fall within what we have called the third period of generative-transformational theory and may now be discussed directly.1 These papers are representative not only of a special interest in semantics on the part of some linguists but of a recent general tendency in theoretical linguistics to emphasize the importance of semantics to linguistic theory. The more or less universal acceptance among transformationalists of the position described in Chomsky’s Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (GT-2) has given way to a far more heterogeneous situation where an increasing concern with the status and function of meaning in a linguistic description has resulted in various proposed revisions of the theory of Aspects, ranging from relatively minor (Chomsky) to quite drastic (Lakoff-1, Fillmore, McCawley).

It is clear that in all of these cases semantic considerations are primary in motivating changes in both syntax and semantics thus indicating a shift in the secondary position of the semantic component characteristic of GT-2. This is not to say that all of these papers bear directly on the theoretical issues mentioned in Table 1. Hale, for example, presents a rather straightforward description of a ritual variation of an Australian language. Dixon is especially difficult to classify; while his background is British and Firthian, his intellectual tastes are quite eclectic as his bibliography includes representatives of most of the major schools of linguistic theory in this century: Hjelmslev, Bloomfield, Chomsky, McCawley, Firth, Halliday, etc. What is perfectly clear is his commitment to semantics as a central focus of linguistic theory.

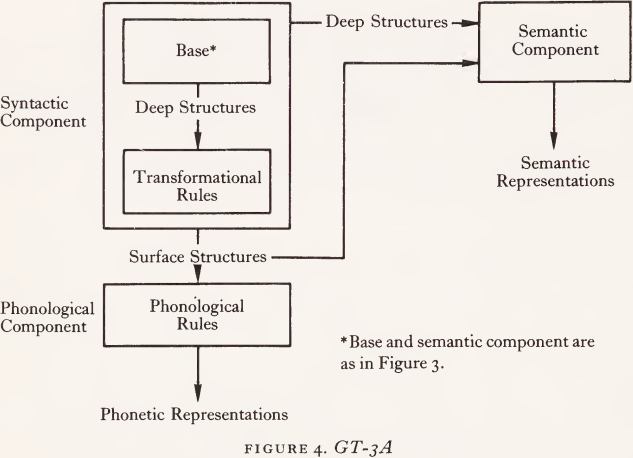

Chomsky’s paper represents the GT-3 A position (Figure 4) (with a semantic component as described by Katz). In it, he defines the standard theory as being equivalent to the theory of Aspects.2 The main effect of Chomsky’s revision of the standary theory (Figure 5) is to modify the requirement that semantic interpretations must be based exclusively on input from the base component in the form of deep structures. On the basis of work by Jackendoff, Kuroda and Emonds he argues that some aspects of meaning can only be accounted for by reference to certain aspects of the surface structure. Crucial to his argument are two semantic notions, focus and presupposition, which also occur in many of the other papers. The focus of a sentence is that part of it which presents new information and is often marked by stress, while the presuppositions of a sentence are those propositions not asserted directly, which the sentences presupposes to be true.

Outside of this change the fundamental assumptions of GT-2 as to the independence of syntax, the interpretive nature of semantics and the independence of syntactic deep structure are retained. Chomsky defines the ‘ standard theory ’ and then argues that various possible alternatives as proposed by his critics differ from it only terminologically and not in terms of having different empirical consequences. Thus, the burden of proof rests on those who claim that syntax and semantics cannot be separated or that a separate level of deep structure does not exist.

It is fair to say that Chomsky now seems to occupy a minority position with regard to these issues. The representation of views in this anthology reflects, I think, the current distribution of opinion among linguists actively working in the area of generative-transformational theory.

The ultimate historical source of this divergence seems to lie in the rejection of a broad definition of meaning by Chomsky in Syntactic Structures leading to the incorporation of a narrowly defined semantic component by Katz and Fodor. As the change from structuralism to GT-1 was encouraged by a concern with syntax so the changes described here have followed from an interest in meaning.

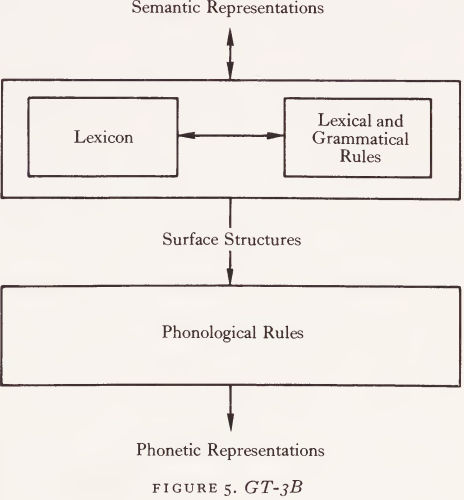

The linguists of GT-3B do not really constitute a unified school. Their common denominator is a conviction that semantic criteria are at least equal in importance to other factors in justifying solutions to linguistic problems and that semantic problems are an appropriate beginning point for a linguistic investigation. Figure 5 presents a very general picture of what seems to be the position of GT-3B linguists.

Efforts to extend the paradigm of GT-2 to an increasingly wider range of linguistic facts have driven the linguists of GT-3B to raise a variety of objections to a number of the fundamental assumptions on which the standard theory is based. McCawley (1968) provides a striking example of this shift. The major portion of this article accepts (though critically) the standard theory which is then rejected in a postscript where many of the arguments found in McCawley (this volume) are presented. One gets a certain sense of historical inevitability when observing this process. The remarks in Lakoff-1 (note a, p. 232) describing the development of generative semantics sound very much like Kuhn’s description of the period when an established paradigm is coming under attack for its failure to solve legitimate problems. If this is the beginning of some sort of linguistic revolution, its magnitude should not be overestimated. The battle between Chomsky and his critics is being fought according to rules which Chomsky himself developed 3 and is essentially a sectarian war among scholars who share a common understanding as to the general goals of linguistic analysis. All agree that the aim of a linguistic description is to explain the relationships between two independently specifiable entities: sound and meaning. Further, it is held that descriptions must contain a lexicon and that transformational rules which map phrase-markers on to other phrase-markers are fundamental mechanisms of linguistic theory. Although the existence of a distinct syntactic level of deep structure may be in dispute, no one denies that a distinction has to be made between surface structures and underlying structures. This shared system of values permits confrontations of a very direct and intense sort among linguists who hold different views.

The key issue between Chomsky and the other linguists of GT-3 is the autonomy of syntax. If no principled boundary can be drawn between these two areas, then there can be no distinct level of syntactic deep structure and the question of whether or not semantics is interpretive becomes irrelevant.

Some of the attacks on the independence of syntax are based on arguments having to do with simplicity and generality of a kind previously familiar in syntactic discussions. Weinreich (in this volume) notes the duplication of effort involved in having a dictionary in the semantic component and a separate lexicon in the syntactic component. In addition, there is another duplication, noted here by Langendoen, arising from the fact that the base of the standard theory generates many deep structures that have no surface realizations and must therefore be blocked by restrictions on the application of transformational rules.

This same ‘filtering ’ must also occur in the semantic component. One of the main points of attack has involved the selectional features of the lexicon, which block such strings as the famous (and grammatical in GT-1) sentence Colorless green ideas sleep furiously, on the grounds that the use of such features as Human or Animate in both the syntactic and semantic components is redundant (Weinreich). In addition, McCawley argues that selectional constraints of this kind are, in any case, semantic rather than syntactic. Further evidence for the lack of separation between syntax and semantics follows from the assertion (developed here in McCawley and Lakoff-1) that deep syntactic structures are equivalent, formally, to semantic representations in that both consist of labeled trees (phrase-markers). McCawley assumes that semantic representations are best described using a revised version of standard symbolic logic and that these hierarchical descriptions are equivalent, as formal objects, to the deep structures of the standard theory. While Bierwisch does not reject the general format of the standard theory his discussion of features in similar logical terms tends to support this argument. Bendix, too, turns to symbolic logic for a notation for semantic descriptions. Another sort of semantic intrusion into syntax is presented by the Kiparskys who argue that semantic factors (especially presuppositions) are necessary to account for certain syntactic relationships. They conclude that base structures must contain semantic information. In general, the thrust of many of the arguments is that the well-formedness of sentences cannot be determined solely on formal or syntactic grounds and further, that the syntactic and semantic information necessary for this determination cannot be separated.

Once the autonomy of syntax has been denied, the existence of a distinct level of syntactic deep structure also becomes unacceptable. It would still be possible to propose a distinct level of deep structure with both syntactic and semantic information in it. In the standard theory (and in Chomsky’s revision of it) it is mandatory that all lexical insertion occur in a block preceding the application of any transformations. Many of the examples in Lakoff-1 attempt to show that some transformation must be applied before some of the lexical material has been inserted and thus that a notion of deep structure defined on this basis is inadequate.

The rejection of interpretive semantics follows immediately from the proposal that syntax and semantics cannot be separated. One style of argument is to show that the relationships between a pair of sentence types cannot be correctly stated if only the purely syntactic deep structures of the standard theory are available.

The semantic motivation of many of the proposed changes in the standard theory has already been noted. The expansion of the domain of linguistic theory, via an expansion of the definition of what is semantic, should also be emphasized. Such semantic notions as presupposition and focus represent a considerable extension over the narrow semantics of Katz and Fodor which concentrated on the detection of anomaly and the specification of the number of readings which could be assigned to sentences. The open ended definition of a semantic representation in Lakoff-1 as ‘ SR — (P1_, PR, Top, F,. . .) ’ suggests that many more semantic concepts will begin to function as requirements on a linguistic analysis with consequences that are difficult to foresee now. The radical expansion in the empirical domain of linguistics is seen clearly in Fillmore’s paper where it is claimed that a lexicon must include information on the ‘ the happiness conditions ’ for the use of a lexical item; that is, the conditions which must be satisfied in order for the item to be used ‘ aptly ’. Bendix explicitly defines his goal as the development of ‘ a form of semantic description that is oriented to the generation of behavioral data, as well as of sentences’.

In Langendoen’s paper it is argued that the definition of linguistic competence must be extended to include knowledge about the use of language and, as Weinreich also suggests, the ability of speakers to impose semantic interpretations on sentences that are semantically, and possibly syntactically, deviant. Chomsky’s paper contains references to the analysis of ‘ discourse ’ and, in general, the papers share the explicit or implicit assumption that the goals of linguistics now must include matters which had previously been entirely ignored or relegated to some non-linguistic area such as ‘performance’. One obvious effect of these changes is to erode the distinction between competence and performance although it is argued in Lakoff-2 that this division can be maintained. Perhaps so, but the expansion of competence must necessarily affect the relationship and may result in attempts to impose purely performance constraints (e.g. memory) on competence models and even a denial that any clear line can be drawn between competence and performance. This suggests that a parallel may exist between syntax/semantics and competence/performance in terms of the historical development of their interrelationships. Katz and Fodor expanded the empirical domain of linguistics to include semantics with the ultimate result that the autonomy of syntax is now seriously questioned by linguists. The autonomy of competence may well be the next victim.

Related to the competence/performance dichotomy is another distinction which promises to be an early casualty. The necessity of separating linguistic knowledge from non-linguistic knowledge of the world (the ‘ dictionary ’ and the ‘ encyclopedia ’) has been emphasized in much contemporary linguistic research. The importance of the independence of linguistic knowledge has rested on the presumed impossibility of handling the total knowledge of speakers in any coherent way. While none of the linguists represented in this anthology are quite willing to give up the possibility of some such distinction the prospects of maintaining a definite boundary do not seem very bright. For example, the content of the presuppositions in Lakoff-2 as to the intelligence and abilities of such objects as goldfish and cats are not strikingly linguistic as this term has been traditionally used.

It is not at all easy to imagine what the final result of this process will be.4 The effect of Syntactic Structures was to narrow the focus of linguistic research to what was felt to be a manageable and relevant part of human language. At the same time, linguistics became a highly empirical science. The conditions for evaluating linguistic theories were explicitly related to the judgments of native speakers as to which strings of words were well-formed as well as to the logical elegance of grammars. It is this empiricism that has been crucial to the changes in the form of linguistic descriptions and to the steady expansion of the proper domain of such descriptions. It is evident that linguistics cannot profitably expand until its domain comes to include everything about human beings that is in some way connected to the acquisition and use of language. The fact that any bit of human knowledge may be involved in the judgments of speakers about the interpretation of sentences is not, in itself, conclusive evidence that such knowledge must be part of a linguistic description, just as individual scholars are motiviated to achieve a distinct identity, so disciplines will ultimately seek to define a clear area of study in which they are supreme. Thus, we might speculate that the next major development in linguistic theory will be an attempt to save an over expanded linguistics by redefining its boundaries relevant to such neighbor areas as psycholinguistics and human communication along lines as yet not clear.

1 References to papers in this volume will use only the author’s name. Lakoff-1 refers to ‘ On Generative Semantics’ and Lakoff-2 to ‘ Presuppositions and Relative Well-Formedness’.

2 Lakoff-1 mistakenly assumes that Chomsky wishes to differentiate these positions. He presents a quotation from Chomsky’s paper which seems to indicate that the form of semantic representations in the standard theory is different from such representations in Aspects. In fact, this quotation is Chomsky’s description of an alternative to the standard theory which he rejects.

3 The extent to which the structure of argumentation in Lakoff-1 is modeled on Chomsky is quite striking. For example, he defines a ‘ basic theory’ and then rejects possible alternatives (including Chomsky’s standard theory) on the grounds, in part, that they do not imply different empirical consequences.

4 Yngve (1969) predicts, with some relish, the demise of linguistics as an independent field. He suggests that the more talented survivors may be incorporated into a broader discipline devoted to the study of human linguistic communication and dominated by the ‘information sciences’. This is not likely to become a popular view among linguists.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)