Semantic theory1

The semantic component interprets underlying phrase-markers in terms of meaning. It assigns semantic interpretations to these phrase-markers which describe messages that can be communicated in the language. That is, whereas the phonological component provides a phonetic shape for a sentence, the semantic component provides a representation of that message which actual utterances having this phonetic shape convey to speakers of the language in normal speech situations.2 We may thus regard the development of a model of the semantic component as taking up the explanation of a speaker’s ability to produce and understand indefinitely many new sentences at the point where the models of the syntactic and phonological components leave off.

If the semantic component is to complete the statement of the principles that provide the speaker with the competence to perform this creative task, it must contain rules that provide a meaning for every sentence generated by the syntactic component. These rules thus explicate the ability a speaker would have were he free of the psychological limitations that restrict him to finite performance. These rules, therefore, explicate an ability to interpret infinitely many sentences. Accordingly, we again face the task offormulating an hypothesis about the nature of a finite mechanism with an infinite output. The hypothesis on which we will base our model of the semantic component is that the process by which a speaker interprets each of the infinitely many sentences is a compositional process in which the meaning of any syntactically compound constituent of a sentence is obtained as a function of the meanings of the parts of the constituent. Hence, for the semantic component to reconstruct the principles underlying the speaker’s semantic competence, the rules of the semantic component must simulate the operation of these principles by projecting representations of the meaning of higher level constituents from representations of the meaning of the lower level constituents that comprise them. That is, these rules must first assign semantic representations to the syntactically elementary constituents of a sentence, then, apply to these representations and assign semantic representations to the constituents at the next higher level on the basis of them, and by applications of these rules to representations already derived, produce further derived semantic representations for all higher level constituents, until, at last, they produce ones for the whole sentence.

The syntactically elementary constituents in underlying phrase-markers are the terminal symbols in these phrase-markers. Actually, these are the morphemes of the language, but since we are simplifying our discussion, we will consider them to be words. Thus, we may say that the syntactic analysis of constituents into lower level constituents stops at the level of words and that these are therefore the atoms of the syntactic system. Accordingly, the semantic rules will have to start with the meanings of these constituents in order to derive the meanings of other constituents compositionally. This means that the semantic component will have two subcomponents: a dictionary that provides a representation of the meaning of each of the words in the language, and a system of projection rules that provide the combinatorial machinery for projecting the semantic representation for all supraword constituents in a sentence from the representations that are given in the dictionary for the meanings of the words in the sentence. We will call the result of applying the dictionary and projection rules to a sentence, i.e., the output of the semantic component for that sentence, a semantic interpretation. There are, therefore, three concepts to explain in order to formulate the model of the semantic component of a linguistic description: dictionary, projection rule, and semantic interpretation.3

Since the meanings of words are not indivisible entities but, rather, are composed of concepts in certain relations to one another, the job of the dictionary is to represent the conceptual structure in the meanings of words. Accordingly, we may regard the dictionary as a finite list of rules, called ‘dictionary entries ’, each of which pairs a word with a representation of its meaning in some normal form. This normal form must be such that it permits us to represent every piece of information about the meaning of a word required by the projection rules in order for them to operate properly. The information in dictionary entries must be full analyses of word meanings.

The normal form is as follows: first, the phonological (or orthographical) representation of the word, then an arrow, then a set of syntactic markers, and finally, n strings of symbols, which we call lexical readings. Each reading will consist of a set of symbols which we call semantic markers, and a complex symbol which we call a selection restriction. (Here and throughout we enclose semantic markers within parentheses to distinguish them from syntactic markers. Selection restrictions are enclosed with angles.) Thus, a dictionary entry, such as the one below, is a word paired with n readings (for it).

Each distinct reading in a dictionary entry for a word represents one of the word’s senses. Thus, a word with n distinct readings is represented as n-ways semantically ambiguous. For example, the word ‘bachelor’ is represented as four-ways semantically ambiguous by the above entry.

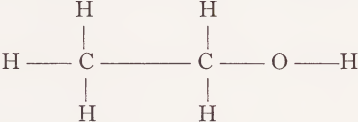

Just as the meaning of a word is not atomic, a sense of a word is not an undifferentiated whole, but, rather, has a complex conceptual structure. The reading which represents a sense provides an analysis of the structure of that sense which decomposes it into conceptual elements and their interrelations. Semantic markers represent the conceptual elements into which a reading decomposes a sense. They thus provide the theoretical constructs needed to reconstruct the interrelations holding between such conceptual elements in the structure of a sense. It is important to stress that, although the semantic markers are given in the orthography of a natural language, they cannot be identified with the words or expressions of the language used to provide them with suggestive labels. Rather, they are to be regarded as constructs of a linguistic theory, just as terms such as ‘force’ are regarded as labels for constructs in natural science. There is an analogy between the formula for a chemical compound and a reading (which may be thought of as a formula for a semantic compound). The formula for the chemical compound ethyl alcohol,

represents the structure of an alcohol molecule in a way analogous to that in which a reading for ‘ bachelor ’ represents the conceptual structure of one of its senses. Both representations exhibit the elements out of which the compound is formed and the relations that form it. In the former case, the formula employs the chemical constructs ‘Hydrogen molecule’, ‘Chemical bond’, ‘Oxygen molecule’, etc., while in the latter, the formula employs the linguistic concepts ‘ (Physical Object) ’, ‘ (Male) ’, ‘(Selection Restriction)’, etc.

The notion of a reading may be extended so as to designate not only representations of senses of words, but also representations of senses of any constituents up to and including whole sentences. We distinguish between ‘lexical readings’ and ‘derived readings,’ but the term ‘reading’ will be used to cover both. The philosopher’s notion of a concept is here reconstructed in terms of the notion of a reading which is either a lexical reading or a derived reading for a constituent less than a whole sentence, while the philosopher’s notion of a proposition (or statement) is reconstructed in terms of the notion of a derived reading for a whole declarative sentence.

Just as syntactic markers enable us to formulate empirical generalizations about the syntactic structure of linguistic constructions, so semantic markers enable us to construct empirical generalizations about the meaning of linguistic constructions. For example, the English words ‘bachelor’, ‘man’, ‘priest’, ‘bull’, ‘uncle’, ‘boy’, etc., have a semantic feature in common which is not part of the meaning of any of the words ‘child’, ‘mole’, ‘mother’, ‘classmate’, ‘nuts’, ‘bolts’, ‘cow’, etc. The first set of words, but not the second, are similar in meaning in that the meaning of each member contains the concept of maleness. If we include the semantic marker (Male) in the lexical readings for each of the words in the first set and exclude it from the lexical entries for each of the words in the second, we thereby express this empirical generalization. Thus, semantic markers make it possible to formulate such generalizations by providing us with the elements in terms of which these generalizations can be stated. Moreover, such semantic generalizations are not restricted to words. Consider the expressions ‘happy bachelor’, ‘my cousin’s hired man’, ‘an orthodox priest I met yesterday ’, ‘ the bull who is grazing in the pasture ’, ‘ the most unpleasant uncle I have’, ‘a boy’, etc., and contrast them with the expressions ‘my favorite child’, ‘the funny mole on his arm’, ‘the whole truth’, ‘your mother’, ‘ his brother’s classmate last year ’, ‘ those rusty nuts and bolts ’, ‘ the cow standing at the corner of the barn ’, etc. Like the case of the previous sets of words, the members of the first of these sets of expressions are semantically similar in that their meanings share the concept maleness, and the members of the second are not semantically similar in this respect either to each other or to the members of the first set. If the dictionary entries for the words ‘bachelor’, ‘man’, ‘priest’, etc., are formulated so that the semantic marker (Male) appears in each, and if the projection rules assign derived readings to these expressions correctly on the basis of the entries for their words, then the semantic marker (Male) will appear in the derived readings for members of the first set but not in derived readings for members of the second. Again, we will have successfully expressed an empirical generalization about the semantics of a natural language. In general, then, the mode of expressing semantic generalizations is the assignment of readings containing the relevant semantic marker(s) to those linguistic constructions over which the generalizations hold and only those.

Semantic ambiguity, as distinct from syntactic ambiguity and phonological ambiguity, has its source in the homonymy of words. Syntactic ambiguity occurs when a sentence has more than one underlying structure. Phonological ambiguity occurs when surface structures of different sentences are given the same phonological interpretation. Semantic ambiguity, on the other hand, occurs when an underlying structure contains an ambiguous word or words that contribute its (their) multiple senses to the meaning of the whole sentence, thus enabling that sentence to be used to make more than one statement, request, query, etc. Thus, a necessary but not sufficient condition for a syntactically compound constituent or sentence to be semantically ambiguous is that it contain at least one word with two or more senses. For example, the source of the semantic ambiguity in the sentence ‘There is no school now ’ is the lexical ambiguity of ‘ school ’ between the sense on which it means sessions of a teaching institution and the sense on which it means the building in which such sessions are held.

But the presence of an ambiguous word is not a sufficient condition for a linguistic construction to be semantically ambiguous. The meaning of other components of the construction can prevent the ambiguous word from contributing more than one of its senses to the meaning of the whole construction. As we have just seen, ‘school’ is ambiguous in at least two ways. But the sentence ‘ The school burned up ’ is not semantically ambiguous because the verb ‘ burn up ’ permits its subject noun to bear only senses that contain the concept of a physical object. This selection of senses and exclusion of others is reconstructed in the semantic component by the device referred to above as a selection restriction. Selection restrictions express necessary and sufficient conditions for the readings in which they occur to combine with other readings to form derived readings. Such a condition is a requirement on the content of these other readings. It is to be interpreted as permitting projection rules to combine readings just in case the reading to which the selection restriction applies contains the semantic markers necessary to satisfy it. For example, the reading for ‘burn up’ will have the selection restriction [(Physical Object)] which permits a reading for a nominal subject of an occurrence of ‘ burn up ’ to combine with it just in case that reading has the semantic marker (Physical Object). This, then, explains why ‘The school burned up’ is unambiguously interpreted to mean that the building burned up. Selection restrictions may be formulated in terms of more complex conditions. We thus allow them to be formulated as Boolean functions of semantic markers. For instance, the selection restriction in the reading for the sense of ‘honest’ on which it means, roughly, ‘characteristically unwilling to appropriate for himself what rightfully belongs to another, avoids lies, deception, etc.’ will be the Boolean function [(Human) & (Infant)], where the bar over a semantic marker requires that the marker not be present in the reading concerned.

We may note further that semantic anomaly is the limiting case of exclusion by the operation of selection restrictions. Semantically anomalous sentences such as ‘ It smells itchy’ occur when the meanings of the component words of a sentence are such that they cannot combine to form a coherent, directly intelligible sentence. The semantic component of a linguistic description explicates such conceptual incongruence as a case where there are two constituents whose combined meanings are essential to the meaning of the whole sentence but where every possible amalgamation of a reading from one and a reading from the other is excluded by some selection restriction. Constituents the sentence level can also be semantically anomalous, e.g., ‘honest baby’ or ‘honest worm’. Thus, in general, a constituent C1 + C2 will be semantically anomalous if, and only if, no reading R1i) of C1 can amalgamate with any reading R2j of C2, i.e., in each possible case, there is a selection restriction that excludes the derived reading Ri,j from being a reading for the constituent C1 + C2. Consequently, the distinction between semantically anomalous and semantically nonanomalous constituents is made in terms of the existence or non-existence of at least one reading for the constituent. We may observe that the occurrence of a constituent without readings is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a sentence to be semantically anomalous. For the sentence ‘We would think it queer indeed if someone were to say that he smells itchy’, which contains a constituent without readings - which is semantically anomalous - is not itself semantically anomalous.

The projection rules of the semantic component for a language characterize the meaning of all syntactically well-formed constituents of two or more words on the basis of what the dictionary specifies about these words. Thus, these rules provide a reconstruction of the process by which a speaker utilizes his knowledge of the dictionary to obtain the meanings of any syntactically compound constituent, including sentences. But, before such rules can operate, it is necessary to extract the lexical readings for the words of a sentence from the dictionary and make them available to the projection rules. That is, it is first necessary to assign sets of lexical readings to the occurrence of words in the underlying phrase-marker undergoing semantic interpretation so that the projection rules will have the necessary material on which to operate. We will simplify our account at this point in order to avoid technicalities with which we do not need to concern ourselves.4

It is at this point that the syntactic information in dictionary entries is utilized. The syntactic markers in the dictionary entry for a word serve to differentiate different words that have the same phonological (or orthographic) representation.

For example, ‘store’ marked as a verb and ‘ store ’ marked as a noun are different words, even though phonologically (or orthographically) these lexical items are identical. Thus, lexical items are distinguished as different words by the fact that the dictionary marks them as belonging to different syntactic categories. Moreover, such pairs of lexical items have different senses so that, in the dictionary, they will be assigned different sets of lexical readings. Thus, it is important to know which of the n different words with the same phonological (or orthographic) representation is the one that occurs at a given point in an underlying phrase-marker because only if we know this can we assign that occurrence of the element in the underlying phrase-marker the right set of lexical readings. Since the underlying phrase-marker will categorize its lowest level elements into their syntactic classes and subclasses, it provides the information needed to decide which of the lexical readings in the dictionary entries for these elements should be assigned to them. All that is required beyond this information is some means of associating each terminal element in an underlying phrase-marker with all and only those lexical readings in its dictionary entry that are compatible with the syntactic categorization it receives in the underlying phrase-marker.

In previous discussions of semantic theory, we suggested a rule of the following sort to fulfill this requirement:

(1) Assign the set of lexical readings R to the terminal symbol  of an underlying phrase-marker just in case there is an entry for

of an underlying phrase-marker just in case there is an entry for  in the dictionary that contains R and that syntactically categorizes the symbol

in the dictionary that contains R and that syntactically categorizes the symbol  in the same way as the labeled nodes dominating

in the same way as the labeled nodes dominating  in the underlying phrase-marker.

in the underlying phrase-marker.

Iterated application of (1) provides a set of readings for each of the words in an underlying phrase-marker. Thus, for example, given (1) and the fact that there will be two distinct entries for ‘store’ such that on one it is a noun while on the other it is a verb, ‘store’ would be assigned a different set of lexical readings in the underlying phrase-marker for ‘The store burned up today’ and in the underlying phrase-marker for ‘The man stores apples in the closet’. When (1) applies no more, the projection rules operate on the underlying phrase-marker.

There is, however, another way of fulfilling this requirement which avoids the postulation of (1). Which way is chosen depends on how the rules in the syntactic component that introduce lexical items into underlying phrase-markers work. If these rules are rewriting rules of the sort illustrated in (3.1)—(3. 10),5 then a rule such as (1) is needed. But if lexical items are inserted into dummy positions in underlying phrase-markers on the basis of a lexical substitution rule in the syntactic component, then we can do away with (1) by allowing the set of readings associated with the lexical item that is substituted to be carried along in the substitution. Since the restrictions on the substitution of a lexical item will be the same as those that are involved in the operation of (1), this procedure will have the same effect as (1). After all lexical substitutions, each lexical item in an underlying phrase-marker will have been assigned its correct set of lexical readings. If it turns out that a lexical substitution rule proves to be better than a set of rewrite rules for introducing lexical items into underlying phrase-markers, the postulation of (1) can be thought of as something that was, but is no longer, necessary to fill a gap that existed in the syntactic component.

Projection rules operate on underlying phrase-markers that are partially interpreted in the sense of having sets of readings assigned only to the lowest level elements in them. They combine readings already assigned to constituents to form derived readings for constituents which, as yet, have had no readings assigned to them. The decision as to which of the readings assigned to nodes of an underlying phrase-marker can be combined by the projection rules is settled by the bracketing in that phrase-marker. That is to say, a pair of readings is potentially combinable if the two are assigned to elements that are bracketed together. Readings assigned to constituents that are not bracketed together cannot be amalgamated by a projection rule. The projection rules proceed from the bottom to the top of an underlying phrase-marker, combining potentially combinable readings to produce derived readings that are then assigned to the node which immediately dominates the nodes with which the originally combined readings were associated. Derived readings provide a characterization of the meaning of the sequence of words dominated by the node to which they are assigned. Each constituent of an underlying phrase-marker is thus assigned a set of readings, until the highest constituent, the whole sentence, is reached and assigned a set of readings, too.

There is a distinct projection rule for each distinct grammatical relation. Thus, there will be different projection rules in the semantic component of a linguistic description for each of the grammatical relations: subject-predicate, verb-object, modification, etc. The number of projection rules required is, consequently, dictated by the number of grammatical relations defined in the theory of the syntactic component. A given projection rule applies to readings assigned to constituents just in case the grammatical relation holding between these constituents is the one with which this projection rule deals. For example, the projection rule (R1) is the one designed to deal with modification, viz., the grammatical relation that holds between a modifier and a head, i.e., such pairs as an adjective and a noun, an adverb and a verb, an adverb and an adjective, etc.

(R1) Given two readings,

R1: (a1), (a2), . . . . , (an) ; (SR1)

R2: (b1, (b2), . . . . , (bm) ; (SR2)

such that R1 is assigned to a node X1 and R2 is assigned to a node X2, X1 dominates a string of words that is a head and X2 dominates a string that is a modifier, and X1 and X2 branch from the same immediately dominating node X,

Then the derived reading,

R3: (a1), (a2), . . . , (an), (b1), (b2), . . . , (bm); (SR1)

is assigned to the node X just in case the selection restriction (SR2) is satisfied by R1 This projection rule expresses the nature of attribution in language, the process whereby new semantically significant constituents are created out of the meanings of modifiers and heads. According to (R1), in an attributive construction, the semantic properties of the new constituent are those of the head except that the meaning of the new constituent is more determinate than that of the head by itself due to the information contributed by the meaning of the modifier. This rule enforces the selection restriction in the reading of the modifier, thus allowing the embedding of a reading for a modifier into a reading for a head only if the latter has the requisite semantic content.

It should not be supposed that other projection rules are essentially the same as (R1), in which the derived reading is formed by taking the union of the sets of semantic markers in the two readings on which it operates. If this were the case, there would be no semantically distinct operations to correspond to, and provide an interpretation of, each distinct grammatical relation. Moreover, the semantic interpretations of sentences such as ‘Police chase criminals’ and ‘ Criminals chase police’ would assign each the same reading for their sentence-constituents, thus falsely marking them as synonymous. That is, since the same sets of semantic markers occur in the lexical readings that are assigned at the level of words in each case, their semantic interpretations would be the same. To indicate the sort of differences that are found among different projection rules, we may consider the projection rules that deal with the grammatical relations of subject-predicate and verb-object in terms of the two examples, ‘ Police chase criminals ’ and ‘ Criminals chase police.’

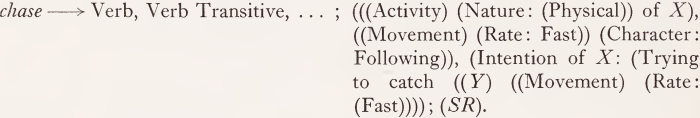

Neglecting the lexical readings for ‘ police ’ and ‘ criminals ’ and other senses of ‘ chase ’, we may begin by considering the most familiar sense of ‘ chase ’:

But before considering the projection rules that combine senses of ‘ police ’ and ‘criminal’ with the sense reconstructed by this lexical reading, it is necessary to consider the motivation for this lexical reading.

The semantic marker (Activity) distinguishes ‘ chase ’ in the intended sense from state verbs, such as ‘sleep’, ‘wait’, ‘suffer’, ‘believe’, etc., and from process verbs, such as ‘grow’, ‘freeze’, ‘dress’, ‘dry’, etc., and classifies ‘chase’ together with other activity verbs, such as ‘eat’, ‘speak’, ‘walk’, ‘remember’, etc. The semantic marker (Activity) is qualified as to nature by the semantic marker (Physical). This indicates that chasing is a physical activity and distinguishes ‘ chase ’ from verbs like ‘think’ and ‘remember’ which are appropriately qualified in their lexical readings to indicate that thinking and remembering are mental activities. But (Activity) is not further qualified, so that, inter alia, ‘ chase ’ can apply to either a group or individual activity. In this respect, ‘chase’ contrasts with ‘mob’ which is marked (Type: (Group)) - hence, we can predict the contradictoriness of ‘ Mary mobbed the movie star (all by herself)’, i.e., both one person did something to the star alone and also more than one did that very thing to the star. Also, ‘ chase ’ contrasts, in this respect, with ‘ solo ’, which is marked (Type: (Individual)) - hence, we can predict that ‘ They solo in the plane on Friday’ has the unique meaning that they each fly the plane by themselves on Friday. Moreover, the semantic marker (Movement) indicates that chasing involves movement of some kind that is left unspecified in the meaning of the verb ‘chase’, in contrast with a verb such as ‘walk’, ‘motor’, or ‘swim’. This movement is necessarily fast, as indicated by the semantic marker (Rate: (Fast)) which distinguishes ‘chase’ from ‘creep’, ‘walk’, ‘move’, etc. Further, this movement has the character of following, as indicated by (Character: (Following)) which distinguishes ‘chase’ from ‘flee’, ‘wander’, etc., and classifies it together with ‘ pursue ’, ‘ trail ’, etc. Again, for someone to be chasing someone or thing, it is not necessary that the person by moving in any specified direction. This fact is marked by the absence of a qualification on (Movement) of the form (Direction: ( )) which would be needed in the lexical readings for ‘ descend ’, ‘ advance ’, ‘ retreat ’, etc. But it is necessary that the person doing the chasing be trying to catch the person or thing he is chasing, so that ‘ chase ’ falls together with the verb ‘ pursue on the one hand, and contrast with ‘follow’, ‘trail’, etc., on the other. This is indicated by (Intention of X: (Trying to catch ((Y) ( )))), where ‘( )’ in the lexical reading under consideration is the semantic marker ((Movement) (Rate: (Fast))) which indicates that the person or thing chased is itself moving fast. It is sometimes held that the person chased must be fleeing from someone or something, but this is mistaken, since a sentence such as ‘ The police chased the speeding motorist ’ does not imply that the motorist is fleeing at all. Finally, note that ‘ chase ’ is not an achievement verb in the sense of applying to cases where a definite goal is obtained. It is not necessary for the person actually to catch the one he is chasing for him to have actually chased him, as is indicated by the nonanomalousness of sentences such as ‘He chased him but did not catch him’. Accordingly, ‘chase’ contrasts with ‘ intercept ’, ‘ trap ’, ‘ deceive ’, etc.

Now, the slots indicated by the dummy markers ‘ X’ and ‘ Y’ determine, respectively, the positions at which readings of the subject and object of ‘ chase ’ can go when sentences containing this verb are semantically interpreted. The projection rule that handles the combination of readings for verbs with readings for their objects embeds the reading for the object of a verb into the Y-slot of the reading for the verb, and the projection rule that handles the combination of readings for predicates and their subjects embeds the reading for the subject into the X-slot of the reading for the predicate. Thus, there are appropriately distinct semantic operations corresponding to the distinct grammatical relations of verb-object and subject-predicate, and the sentence-readings for the two sentences ‘Police chase criminals’ and ‘ Criminals chase police ’ are appropriately different.

Preliminary to defining the concept ‘semantic interpretation of the sentence S’, we must define the subsidiary notion ‘ semantically interpreted underlying phrase-marker of S’. We define it as a complete set of pairs, one member of which is a labeled node of the underlying phrase-marker, and the other member of which is a maximal set of readings, each reading in this set being a reading for the sequence of words dominated by the labeled node in question. The set of readings is maximal in the sense that it contains all and only those readings of the sequence of words that belong to it by virtue of the dictionary, the projection rules, and the labeled bracketing in the underlying phrase-marker. The set is complete in the sense that every node of the underlying phrase-marker is paired with a maximal set of readings. In terms of this definition for ‘semantically interpreted underlying phrase-markers of S’, we can define the notion ‘semantic interpretation of an underlying phrase-marker of S’ to be (1) a semantically interpreted underlying phrase-marker of S, and (2) the set of statements that follow from (1) by definitions (D1)-(D6) and any further such definitions that are specified in the theory of language,6 where ‘ C’ is any constituent of any underlying phrase-marker of S,

(D1) C is semantically anomalous if and only if the set of readings assigned to C contains no members.

(D 2) C is semantically unambiguous if and only if the set of readings assigned to C contains exactly one member.

(D 3) C is semantically ambiguous n-ways if and only if the set of readings assigned to C contains n members, for n greater than 1.

(D4) C1 and C2 are synonymous on a reading if and only if the set of readings assigned to C1 and the set of readings assigned to C2 have at least one member in common.

(D 5) C1 and C2 are fully synonymous if and only if the set of readings assigned to C1 and the set of readings assigned to C2 are identical.

(D6) C1 and C2 are semantically distinct if and only if each reading in the set assigned to C1 differs by at least one semantic marker from each reading in the set assigned to C2.

We can now define the notion ‘ semantic interpretation of the sentence S ’ as (1) the set of semantic interpretations of *S’s underlying phrase-markers, and (2) the set of statements about S that follows from (1) and definitions (D'1)-(D'3) and any further such definitions that are specified in the theory of language, where ‘sentence-constituent’ refers to the entire string of terminal symbols in an underlying phrase-marker

(D'O S is semantically anomalous if and only if the sentence-constituent of each semantically interpreted underlying phrase-marker of S is semantically anomalous.

(D'2) S is semantically unambiguous if and only if each member of the set of readings which contains all the readings that are assigned to sentence-constituents of semantically interpreted underlying phrase-marker of S is synonymous with each other member.

(D'3) S is semantically ambiguous n-ways if and only if the set of all readings assigned to the sentence-constituents of semantically interpreted underlying phrase-markers of S contains n nonequivalent readings, for n greater than 1.

This way of defining semantic concepts, such as ‘ semantically anomalous sentence in L’, ‘semantically ambiguous sentence in L’, ‘synonymous constituents in L’, etc., removes any possibility of criticizing the theory of language in which these concepts are introduced on the grounds of circularity in definition of the sort for which Quine had criticized Carnap’s attempts to define the same range of concepts. The crucial point about this way of defining these concepts is that their defining condition is stated solely in terms of formal features of semantically interpreted underlying phrase-markers so that none of these concepts themselves need appear in the definition of any of the others. Moreover, these definitions also avoid the charge of empirical vacuity that was correctly made against Carnap’s constructions. These definitions enable us to predict semantic properties of syntactically well-formed strings of words in terms of formal features of semantically interpreted underlying phrase-markers. The adequacy of these definitions is thus an empirical question about the structure of language. Their empirical success depends on whether, in conjunction with the set of semantically interpreted underlying phrase-markers for each natural language, they correctly predict the semantic properties and relations of the sentences in each natural language.

The semantic interpretations of sentences produced as the output of a semantic component constitute the component’s full account of the semantic structure of the language in whose linguistic description the component appears. The correctness of the account that is given by the set of semantic interpretations of sentences is determined by the correctness of the individual predictions contained in each semantic interpretation. These are tested against the intuitive judgments of fluent speakers of the language. For example, speakers of English judge that the syntactically unique sentence ‘ I like seals’ is semantically ambiguous. An empirically correct semantic component will have to predict this ambiguity on the basis of a semantically interpreted underlying phrase-marker for this sentence in which its sentence-constituent is assigned at least two readings. Also, English speakers judge that ‘ I saw an honest stone ’ or ‘ I smell itchy ’ are semantically anomalous, as are ‘ honest stones ’ and ‘ itchy smells ’. Hence, an adequate semantic component will have to predict these anomalies on the basis of semantically interpreted underlying phrase-markers in which the relevant constituents are assigned no readings. Furthermore, English speakers judge that ‘ Eye doctors eye blondes ‘ Oculists eye blondes ’, and ‘ Blondes are eyed by oculists’ are synonymous sentences, i.e., paraphrases of each other, while ‘ Eye doctors eye what gentlemen prefer ’ is not a paraphrase of any of these sentences. Accordingly, a semantic component will have to predict these facts. In general, a semantic component for a given language is under the empirical constraint to predict the semantic properties of sentences in each case where speakers of the language have strong, clear-cut intuitions about the semantic properties and relations of those sentences. Where there are no strong, clear-cut intuitions, there will be no data one way or the other. But, nevertheless, the semantic component will still make predictions about such cases by interpolating from the clear cases on the basis of the generalizations abstracted from them.

Therefore, the empirical evaluation of the dictionary entries and projection rules of a semantic component is a matter of determining the adequacy of the readings that they assign to constituents, and this, in turn, is a matter of determining the adequacy of the predictions that follow from these readings and the definitions of semantic properties and relations in the theory of language. If the intuitive judgments of speakers are successfully predicted by a semantic component, the component gains proportionately in empirical confirmation. If, on the other hand, the semantic component makes false predictions then, as with any scientific theory, the system has to be revised in such a way that prevents these empirically inadequate predictions from being derivable from the dictionary and projection rules. However, deciding which part(s) of the component have been incorrectly formulated is not something that can always, or even very often, be done mechanically. Rather, it is a matter of further theory construction. We have to make changes which seem necessary to prevent the false predictions and then check out these changes to determine if they avoid the false predictions and do not cause special difficulties of their own. Thus, we are always concerned with the over-all adequacy of the semantic component, and it is on this global basis that we judge the adequacy of its subcomponents. The adequacy of a dictionary entry or a projection rule depends, then, on how well it plays its role within the over-all descriptive system.

1 This paper is reprinted from J. J. Katz, The Philosophy of Language, pp. 151-75.

2 This conception of the semantic component is elaborated in J. J. Katz and J. A. Fodor, ‘The Structure of a Semantic Theory’, Language, xxxIx, 170-210, 1963; reprinted in Fodor and Katz (eds.), The Structure of Language: Readings in the Philosophy of Language. It is also elaborated in J. J. Katz, ‘ Analyticity and Contradiction in Natural Language’ (same volume), and in Katz and Postal, An Integrated Theory of Linguistic Descriptions

3 The discussion to follow will explain these three concepts. Roughly, the dictionary stores basic semantic information about the language, the projection rules apply this information in the interpretation of syntactic objects, and semantic interpretations are full representations of the semantic structure of sentences given by the operation of the projection rules.

4 The assignment of lexical readings is actually accomplished by the same device that introduces the lexical items themselves, but, for the sake of avoiding complications, we shall not go into the formal structure of this device here. Cf. N. Chomsky, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, and J. J. Katz, Semantic Theory.

5 See J. J. Katz, The Philosophy of Language, chapter 3, pp. 126-7. The distinction here is between rules of the sort appearing in Syntactic Structure for insertion of lexical items and those appearing in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax for the same purpose.

6 These further definitions include all those given in Katz, ‘Analyticity and Contradiction in Natural Language’, those for concepts such as presupposition of the question (or imperative) S and possible answer to the question S, which are given in Katz and Postal, An Integrated Theory of Linguistic Descriptions, and any other definitions of semantic properties and relations that can be given in terms of configurations of symbols in semantically interpreted underlying phrase-markers.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة