Presupposition

These syntactic differences are correlated with a semantic difference. The force of the that-clause is not the same in the two sentences

It is odd that it is raining (factive)

It is likely that it is raining (non-factive)

or in the two sentences

I regret that it is raining (factive)

I suppose that it is raining (non-factive).

The first sentence in each pair (the factive sentence) carries with it the presupposition ‘it is raining’. The speaker presupposes that the embedded clause expresses a true proposition, and makes some assertion about that proposition. All predicates which behave syntactically as factives have this semantic property, and almost none of those which behave syntactically as non-factives have it.1 This, we propose, is the basic difference between the two types of predicates. It is important that the following things should be clearly distinguished:

(1) Propositions the speaker asserts, directly or indirectly, to be true

(2) Propositions the speaker presupposes to be true.

Factivity depends on presupposition and not on assertion. For instance, when someone says

It is true that John is ill

John turns out to be ill

he is asserting that the proposition ‘John is ill’ is a true proposition, but he is not presupposing that it is a true proposition. Hence these sentences do not follow the factive paradigm:

*John’s being ill is true

*John’s being ill turns out

*The fact of John’s being ill is true

*The fact of John’s being ill turns out.

The following sentences, on the other hand, are true instances of presupposition:

It is odd that the door is closed

I regret that the door is closed.

The speaker of these sentences presupposes ‘the door is closed’ and furthermore asserts something else about that presupposed fact. It is this semantically more complex structure involving presupposition that has the syntactic properties we are dealing with here.

When factive predicates have first person subjects it can happen that the top sentence denies what the complement presupposes. Then the expected semantic anomaly results. Except in special situations where two egos are involved, as in the case of an actor describing his part, the following sentences are anomalous:

*I don’t realize that he has gone away

*I have no inkling that a surprise is in store for me.2

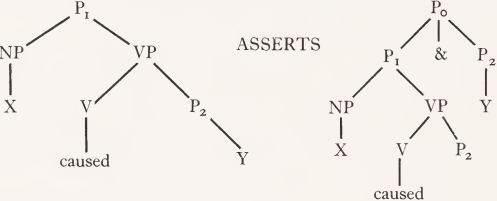

Factivity is only one instance of this very basic and consequential distinction. In formulating the semantic structure of sentences, or, what concerns us more directly here, the lexical entries for predicates, we must posit a special status for presuppositions, as opposed to what we are calling assertions. The speaker is said to ‘ assert ’ a sentence plus all those propositions which follow from it by virtue of its meaning, not, e.g., through laws of mathematics or physics.3 Presumably in a semantic theory assertions will be represented as the central or ‘core’ meaning of a sentence - typically a complex proposition involving semantic components like ‘ S1 cause S2’, ‘S become’, ‘N want S’ - plus the propositions that follow from it by redundancy rules involving those components. The formulation of a simple example should help clarify the concepts of assertion and presupposition.

Mary cleaned the room.

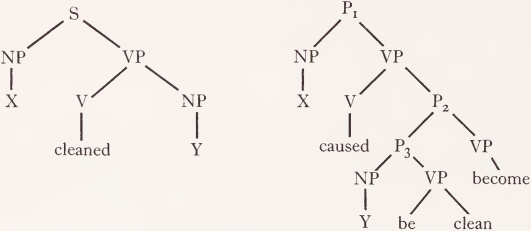

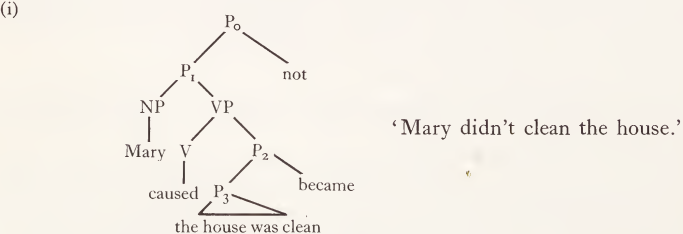

The dictionary contains a mapping between the following structures:

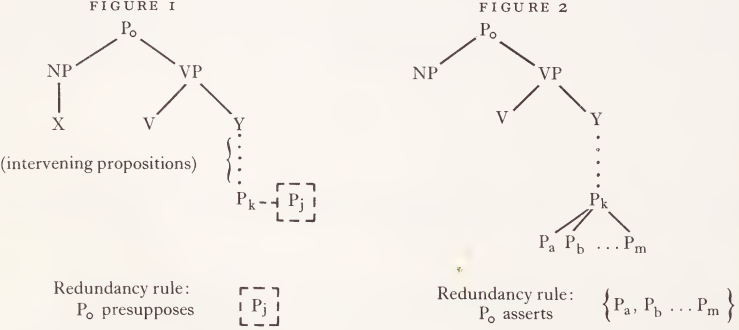

where S refers to the syntactic object ‘Sentence’ and P to the semantic object ‘Proposition’.

A redundancy rule states that the object of ‘cause’ is itself asserted:

This rule yields the following set of assertions:

X caused4 Y to become clean

Y became clean.

(Why the conjunction of P1 and P2 is subordinated to P0 will become clear, especially in (3) and (5).)

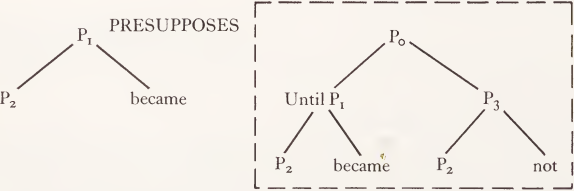

Furthermore, there is a presupposition to the effect that the room was dirty before the event described in the sentence. This follows from ‘become’, which presupposes that its complement has, up to the time of the change referred to by ‘become’, not been true. This may be expressed as a redundancy rule:

(Presuppositions will be enclosed in dotted lines. Within the context of a tree diagram representing the semantic structure of a sentence presuppositions which follow from a specific semantic component will be connected to it by a dotted line.)

That this, like the factive component in regret or admit, is a presupposition rather than an assertion can be seen by applying the criteria in the following paragraphs.

(1) Presuppositions are constant under negation. That is, when you negate a sentence you don’t negate its presuppositions; rather, what is negated is what the positive sentence asserts. For example,

Mary didn’t clean the room

unlike its positive counterpart does not assert either that the room became clean or, if it did, that it was through Mary’s agency. On the other hand, negation does not affect the presupposition that it was or has been dirty. Similarly, these sentences with factive predicates (underlined) -

It is not odd that the door is closed

John doesn’t regret that the door is closed

presuppose, exactly as do their positive counterparts, that the door is closed. In fact, if you want to deny a presupposition, you must do it explicity:

Mary didn’t clean the room; it wasn’t dirty

Legree didn’t force them to work; they were willing to

Abe didn’t regret that he had forgotten; he had remembered.

The second clause casts the negative of the first into a different level; it’s not the straightforward denial of an event or situation, but rather the denial of the appropriateness of the word in question (underlined above). Such negations sound best with the inappropriate word stressed.

(2) Questioning, considered as an operation on a proposition P, indicates ‘I do not know whether P’. When I ask

Are you dismayed that our money is gone?

I do not convey that I don’t know whether it is gone but rather take that for granted and ask about your reaction.

(Note that to see the relation between factivity and questioning only yes-no questions are revealing. A question like

Who is aware that Ram eats meat

already by virtue of questioning an argument of aware, rather than the proposition itself; presupposes a corresponding statement:

Someone is aware that Ram eats meat.

Thus, since presupposition is transitive, the who-question presupposes all that the someone-statement does.)

Other presuppositions are likewise constant under questioning. For instance: a verb might convey someone’s evaluation of its complement as a presupposition. To say ‘they deprived him of a visit to his parents’ presupposes that he wanted the visit (vs. ‘ spare him a visit. . . ’). The presupposition remains in ‘ Have they deprived him of a. .. ? ’ What the question indicates is ‘ I don’t know whether they have kept him from. . . ’

(3) It must be emphasized that it is the set of assertions that is operated on by question and negation. To see this, compare -

Mary didn’t kiss John

Mary didn’t clean the house.

They have certain ambiguities which, as has often been noted, are systematic under negation. The first may be equivalent to any of the following more precise sentences:

Someone may have kissed John, but not Mary

Mary may have kissed someone, but not John

Mary may have done something, but not kiss John

Mary may have done something to John, but not kiss him.

And the second:

Someone may have cleaned the house, but not Mary

Mary may have cleaned something, but not the house

Mary may have done something, but not clean the house

Mary may have done something to the house, but not clean it.

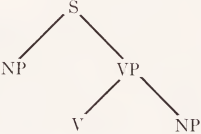

All of these readings can be predicted on the basis of the constituent structure:

Roughly, each major constituent may be negated.

But the second sentence has still another reading:

Mary may have been cleaning the house,

but it didn’t get clean.

That extra reading has no counterpart in the other sentence. Clean is semantically more complex than kiss in that whereas kiss has only one assertion (press the lips against), clean has two, as we have seen above. How this affects the meaning of the negative sentence can be seen through a derivation:

(ii) Application of redundancy rule on ‘cause ’:

‘It’s not the case that both Mary cleaned the house and the house is clean.’

(iii) DeMorgan’s Law yields

‘Either “Mary didn’t clean the house” or “the house didn’t get clean”.’

Thus to say Mary didn't clean the house is to make either of the two negative assertions in (iii). The remaining readings arise from distribution of not over the constituents of the lexicalized sentence.

Presumably the same factors account for the corresponding ambiguity of Did Mary clean the house?

(4) If we take an imperative sentence like

(You) chase that thief!

to indicate something like

I want (you chase that thief)

then what ‘I want’ doesn’t include the presuppositions of S. For example, S presupposes that

That thief is evading you

but that situation is hardly part of what ‘I want’.

The factive complement in the following example is likewise presupposed independently of the demand:

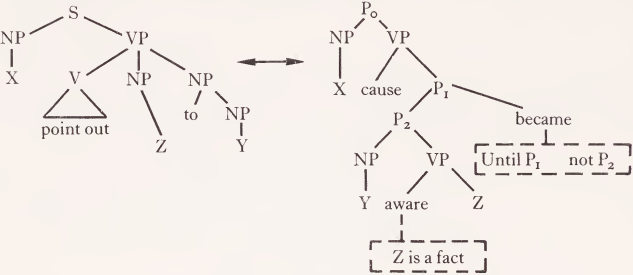

Point it out to 006 that the transmitter will function poorly in a cave.

Assume the dictionary contains this mapping:

From the causative redundancy rule, which adds the assertion P1, the definition of point out and the fact that want distributes over subordinate conjuncts, it follows that the above command indicates

I want 006 to become aware that the transmitter.. .

However it doesn’t in any way convey

I want the transmitter to function poorly in a cave

nor, of course, that

I want 006 not to have been aware. ..

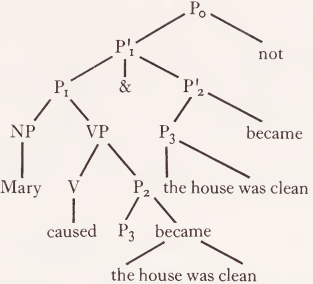

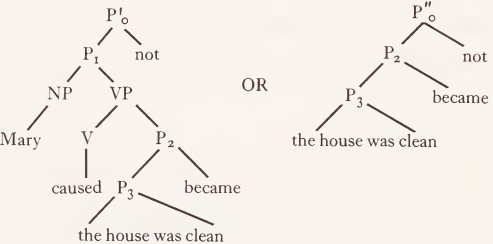

(5) We have been treating negation, questioning and imperative as operations on propositions like implicit ‘higher sentences’. Not surprisingly explicit ‘higher sentences ’ also tend to leave presuppositions constant while operating on assertions. Our general claim is that the assertions of a proposition (Pk) are made relative to that proposition within its context of dominating propositions. Presuppositions, on the other hand, are relative to the speaker. This is shown in figures 1 and 2. Fig. 1 shows that the presuppositions of Pk are also presupposed by the whole proposition P0. In fig. 2 we see that whatever P0 asserts about Pk it also asserts about the set (see (3) above) of propositions that Pk asserts.

Let us further exemplify this general claim:

John appears to regret evicting his grandmother.

Since appear is not factive this sentence neither asserts nor presupposes

John regrets evicting her.

However it does presuppose the complement of the embedded factive verb regret, as well as the presupposition of evict to the effect that he was her landlord.

It does not matter how deeply the factive complement (italicized) is embedded:

Abe thinks it is possible that Ben is becoming ready to encourage Carl to acknowledge that he had behaved churlishly.

This claim holds for presuppositions other than factivity. We are not obliged to conclude from

John refuses to remain a bachelor all his life

that he plans to undergo demasculating surgery, since bachelor asserts unmarried, but only presupposes male and adult. Thus (ii) yields:

John refuses to remain unmarried all his life

but not

John refuses to remain male (adult) all his life.

(6) A conjunction of the form S1 and S2 too serves to contrast an item in S1 with one in S2 by placing them in contexts which are in some sense not distinct from each other. For instance:

Tigers are ferocious and panthers are (ferocious) too

*Tigers are ferocious and panthers are mild-mannered too.

Abstracting away from the contrasting items, S1 might be said to semantically include S2. The important thing for us to notice is that the relevant type of inclusion is assertion. Essentially, S2 corresponds to an assertion of S1. To see that presupposition is not sufficient consider the following sentences. The second conjunct in each of the starred sentences corresponds to a presupposition of the first conjunct, while in the acceptable sentences there is an assertion relationship.

John deprived the mice of food and the frogs didn’t get any either

*John deprived the mice of food and the frogs didn’t want any either

John forced the rat to run a maze and the lizard did it too

*John forced the rat to run a maze and the lizard didn’t want to either

Mary’s refusal flabbergasted Ron, and he was surprised at Betty’s refusal too

*Mary’s refusal flabbergasted Ron and Betty refused too.

1 There are some exceptions at this second half of our generalization. Verbs like know, realize, though semantically factive, are syntactically non-factive, so that we cannot say *I know the fact that John is here, *I know John's being here, whereas the propositional constructions are acceptable: I know him to be here. There are speakers for whom many of the syntactic and semantic distinctions we bring up do not exist at all. Professor Archibald Hill has kindly informed us that for him factive and non-factive predicates behave in most respects alike and that even the word fact in his speech has lost its literal meaning and can head clauses for which no presupposition of truth is made. We have chosen to describe a rather restrictive type of speech (that of C.K.) because it yields more insight into the syntactic-semantic problems with which we are concerned.

2 In some cases what at first sight looks like a strange meaning-shift accompanies negation with first person subjects. The following sentences can be given a non-factive interpretation which prevents the above kind of anomaly in them:

I’m not aware that he has gone away

I don’t know that this isn’t our car.

It will not do to view these non-factive that-clauses as indirect questions:

*I don’t know that he has gone away or not.

We advance the hypothesis that they are deliberative clauses, representing the same construction as clauses introduced but that:

I don’t know but that this is our car.

This accords well with their meaning, and especially with the fact that deliberative but that-clauses (in the dialects that permit them at all) are similarly restricted to negative sentences with first person subjects:

*1 know but that this is our car

*John doesn’t know but that this is our car.

3 We prefer ‘ assert ’ to ‘ imply ’ because the latter suggests consequences beyond those based on knowledge of the language. This is not at all to say that linguistic knowledge is disjoint from other knowledge. We are trying to draw a distinction between two statuses a defining proposition can be said to have in the definition of a predicate, or meaning of a sentence, and to describe some consequences of this distinction. This is a question of the semantic structure of words and can be discussed independently of the question of the relationship between the encyclopedia and the dictionary.

4 Though we cannot go into the question here, it is clear that the tense of a sentence conveys information about the time of its presuppositions as well as of its assertions, direct and indirect. Thus tense (and likewise mood, cf. p. 367 below) is not an ‘operator’ in the sense that negation.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة