Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

SEMANTICS AND SITUATION

المؤلف:

R. M. W. DIXON

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

451-25

2024-08-19

1275

SEMANTICS AND SITUATION

There are two sides to linguistic meaning: sense and reference. Taking Lyons’s definitions, the sense of a word is ‘its place in a system of relationships which it contracts with other words in the vocabulary’. By semantic description, in this paper, we mean sense description; a word is semantically related to other words through their sense descriptions involving common features or else different features from the same system, or through their being defined one in terms of another or all in terms of some other, nuclear, word. Reference is ‘the relationship which holds between words and the things, events, actions and qualities they “stand for” ’ (Lyons 1968.427, 424).

We have suggested sense descriptions in terms of systems of semantic features. Now each feature has reference, but this reference is relative to the reference of the other features in the system. Using ‘situation’ to refer to non-language phenomena, we can talk of the relative ‘situational realizations’ (rather than reference) of the features in a semantic system; this has some similarities to the statement of phonetic realizations for phonological features.1 For example (oversimplifying a little), balgan ‘hit with a stick or other long rigid object, held in the hand’ and bundyun ‘hit with the hand (unclenched) or with a long flexible object such as a bramble or strap [held in the hand] ’ differ only in the features ‘ long rigid implement’ and ‘long flexible implement’, having in common the features ‘affect by striking’ and ‘held onto’.2 The situational realizations are relative: balgan implies a more rigid object and bundyun a less rigid one. The realization of balgan cannot just be given, in isolation, in terms of ‘rigid object’; but since ‘rigid object’ is specified in the semantic description of balgan it is implied that a different word is used in the case of relatively 'non-rigid objects’, i.e. bundyun. That is, balgan and its situational realization are, on one dimension, complementary to bundyun and its situational realization; the situational realization of balgan can only significantly be given with respect to the situational realization of bundyun.

Situational realizations are stated for elements in the semantic description of Dyirbal. Given the semantic description of a sentence (together with its inter¬ relating grammatical description) we can provide a situational interpretation, that specifies the types of events that the sentence could refer to. We cannot work the other way round: given a situational description, we cannot from this produce a semantic description. That is, we can have ‘ situational interpretations ’ of semantic descriptions but not ‘ situational feed-in ’ to semantics, generating a suitable semantic description. The reason for this lies partly in the fact that a particular situational phenomenon may be, in different instances, the realization of different semantic categories (that is, there is overlapping of situational realizations) depending on (1) the situational environment, and/or (2) the semantic oppositions in a particular text. Taking these in turn:

(1) a certain intensity of gaze - measured perhaps by size of eye and pupil, rate of blinking, time focussed on a single object - could realize either buɽan ‘ look ’ or ŋaɽnydyanyu ‘stare’ depending on the situational environment. An intensity of gaze that in a casual, informal setting might be considered a little piercing could well be the realization of ŋaɽnydyanyu relative to a less intense look as realization of buɽan. But in a more formal, ceremonial say, setting, this might be a quite usual intensity and be the realization of buɽan, relative to a really intense stare being the realization of ŋaɽnydyanyu.

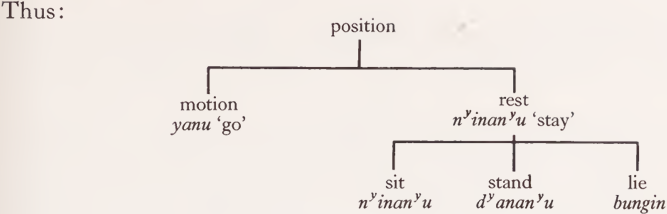

(2) nyinanyu has a generic meaning ‘stay (in camp)’ (whatever the various postures adopted - sitting, standing, lying) as opposed to motion verbs such as yanu ‘ go ’; and also a particular meaning ‘ sit ’ as opposed to dyananyu ‘ stand ’ and bungin ‘lie’.

The semantic description of nyinanyu is (position, rest; intr) for its generic sense; (position, rest, sit; intr) for the more specific sense. Now suppose that everyone, bar one man and one woman, is leaving a camp; the man is standing watching the others leave. An observer could appropriately say balamangan yanu/bayi yaɽa nyinanyu ‘they are all going but the man is staying’, comparing the events of the people leaving, and the man remaining in the camp. Or else the observer could equally appropriately say balan dyugumbil nyinanyu/bayi yaɽa dyananyu ‘the woman is sitting down and the man standing up ’, comparing the events of the woman sitting in the camp and the man standing there. Here a single event - the man standing - can be the realization of nyinanyu (relative to the realization of yanu) or else of dyananyu (relatives to the realization of nyinanyu), depending entirely on the semantic oppositions in the text.3

It will be seen from these examples that it is not possible to take an isolated situational event, and demand that the linguistic description of a language should be able to indicate a language description of it. (Thus the view that language essentially works by being given ‘real events’ and providing word pictures of them is, on the most literal level, erroneous.) A particular correspondence between a situational event, and an occurrence of a piece of language, is relative to (and determined by) the grammatical and semantic systems of the language, the semantic oppositions in the text to which the piece of language belongs, and the ‘(anthropological/sociological) situational system’ of the culture (such as that dealing with ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ settings, and so on). What can be stated is a range of (relative) situational realizations for a semantic category, and thus for a sentence. This range can be reduced by considering the particular semantic oppositions in a text that includes the sentence. It may be still further reduced by considering the description of the situation in which the text occurs, or to which it refers (if it is a narrative, say) and so on, in terms of some suitable theory of situational organization (if such a theory should ever be put forward).

1 For instance, in Dyirbal [ε] can be the phonetic realization of either /a/ or /i/ - of /a/ in a palatal environment and of /i/ in a non-palatal environment. Only statements of relative realization can be given for the members of a phonological system. Thus we can only say that the realization of /i/ is relatively less open than the realization of /a/ — that is, in a particular environment /i/ will be realized by a less open vowel than /a/. But the most open realization (over all possible environments) of /i/ is in fact more open than the least open realization (over all possible environments) of /a/.

2 More strictly, balgan implies ‘hit with a long rigid object, held on to’, minban ‘hit with a long rigid object, let go of’, and bunydyun ‘hit with a long flexible object’; bunydyun does not involve any specification ‘held on to’ as opposed to ‘let go of’ but in fact the long flexible objects used by the Dyirbal are always held onto since they would be ineffective thrown.

3 The semantic oppositions here (yanu contrasting with nyinanyu, or nyinanyu contrasting with dyananyu) are contrastive correlations of the sort discussed in detail in Dixon 1965.111-4 ff. A text in any language can be exhaustively analyzed into contrastive and replacement correlations that specify the semantic form and plot of the text. Such textual correlations involve limited selection from the full semantic possibilities of the language. A considerable quantity of Dyirbal text material was analyzed into contrastive and replacement correlations and the results used - together with Dyalŋuy and other types of data - in deciding upon correct semantic descriptions. For more details see Dixon 19683.251-4; and see also n. a, p. 456 and n. a, p. 468, below.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)