Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 2024-11-09

Date: 2024-10-26

Date: 2024-11-11

|

With the exception of glottal, each place of articulation has a pair of phonemes, one fortis and one lenis. This is similar to what was seen with the plosives. The fortis fricatives are said to be articulated with greater force than the lenis, and their friction noise is louder. The lenis fricatives have very little or no voicing in initial and final positions, but may be voiced when they occur between voiced sounds. The fortis fricatives have the effect of shortening a preceding vowel in the same way as fortis plosives do. Thus in a pair of words like 'ice' aIs and 'eyes' aIz, the aI diphthong in the first word is considerably shorter than aI in the second. Since there is only one fricative with glottal place of articulation, it would be rather misleading to call it fortis or lenis (which is why there is a line on the chart above dividing h from the other fricatives).

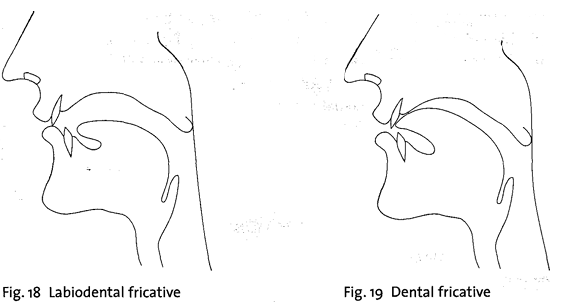

We will now look at the fricatives separately, according to their place of articulation. f, v (example words: 'fan', 'van'; 'safer', 'saver'; 'half, 'halve')

These are labiodental: the lower lip is in contact with the upper teeth as shown in Fig. 18. The fricative noise is never very strong and is scarcely audible in the case of v.

T, D (example words: 'thumb', 'thus'; 'ether', 'father'; 'breath', 'breathe')

The dental fricatives are sometimes described as if the tongue were placed between the front teeth, and it is common for teachers to make their students do this when they are trying to teach them to make this sound. In fact, however, the tongue is normally placed behind the teeth, as shown in Fig. 19, with the tip touching the inner side of the lower front teeth and the blade touching the inner side of the upper teeth. The air escapes through the gaps between the tongue and the teeth. As with f, v, the fricative noise is weak.

s, z (example words: 'sip', 'zip'; 'facing', 'phasing'; 'rice, 'rise')

These are alveolar fricatives, with the same place of articulation as t, d. The air escapes through a narrow passage along the centre of the tongue, and the sound produced is comparatively intense. The tongue position is shown in Fig. 16 earlier.

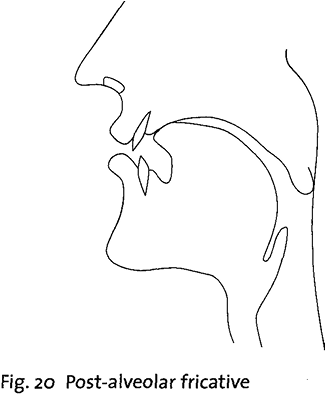

ʃ , Ʒ (example words: 'ship' (initial 3 is very rare in English); 'Russia', 'measure'; 'Irish', 'garage') These fricatives are called post-alveolar, which can be taken to mean that the tongue is in contact with an area slightly further back than that for s, z (see Fig. 20). If you make s, then ʃ, you should be able to feel your tongue move backwards.

The air escapes through a passage along the centre of the tongue, as in s, z, but the passage is a little wider. Most BBC speakers have rounded lips for ʃ , Ʒ, and this is an important difference between these consonants and s, z. The fricative ʃ is a common and widely distributed phoneme, but Ʒ is not. All the other fricatives described so far (f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ) can be found in initial, medial and final positions, as shown in the example words. In the case of Ʒ, however, the distribution is much more limited. Very few English words begin with Ʒ (most of them have come into the language comparatively recently from French) and not many end with this consonant. Only medially, in words such as 'measure' meƷə, 'usual' ju:Ʒuəl is it found at all commonly.

h (example words: 'head', 'ahead', 'playhouse')

The place of articulation of this consonant is glottal. This means that the narrowing that produces the friction noise is between the vocal folds. If you breathe out silently, then produce h, you are moving your vocal folds from wide apart to close together. However, this is not producing speech. When we produce h in speaking English, many different things happen in different contexts. In the word 'hat', the h is followed by an as vowel. The tongue, jaw and lip positions for the vowel are all produced simultaneously with the h consonant, so that the glottal fricative has an æ quality. The same is found for all vowels following h; the consonant always has the quality of the vowel it precedes, so that in theory if you could listen to a recording of h-sounds cut off from the beginnings of different vowels in words like 'hit', 'hat', 'hot', 'hut', etc., you should be able to identify which vowel would have followed the h. One way of stating the above facts is to say that phonetically h is a voiceless vowel with the quality of the voiced vowel that follows it.

Phonologically, h is a consonant. It is usually found before vowels. As well as being found in initial position it is found medially in words such as 'ahead' shed, 'greenhouse' gri:nhaUs, 'boathook' bəʊthʊk. It is noticeable that when h occurs between voiced sounds (as in the words 'ahead', 'greenhouse'), it is pronounced with voicing - not the normal voicing of vowels but a weak, slightly fricative sound called breathy voice. It is not necessary for foreign learners to attempt to copy this voicing, although it is important to pronounce h where it should occur in BBC pronunciation. Many English speakers are surprisingly sensitive about this consonant; they tend to judge as sub-standard a pronunciation in which h is missing. In reality, however, practically all English speakers, however carefully they speak, omit the h in non-initial unstressed pronunciations of the words 'her', 'he', 'him', 'his' and the auxiliary 'have', 'has', 'had', although few are aware that they do this.

There are two rather uncommon sounds that need to be introduced; since they are said to have some association with h, they will be mentioned here. The first is the sound produced by some speakers in words which begin orthographically (i.e. in their spelling form) with 'wh'; most BBC speakers pronounce the initial sound in such words (e.g. 'which', 'why', 'whip', 'whale') as w, but there are some (particularly when they are speaking clearly or emphatically) who pronounce the sound used by most American and Scottish speakers, a voiceless fricative with the same lip, tongue and jaw position as w. The phonetic symbol for this voiceless fricative is AY. We can find pairs of words showing the difference between this sound and the voiced sound w:

'witch' wɪtʃ

'wail' weɪl

'Wye' waɪ

'wear' weə

'which' Mɪtʃ

'whale' Meɪl

'why' Maɪ

'where' Meə

The obvious conclusion to draw from this is that, since substituting one sound for the other causes a difference in meaning, the two sounds must be two different phonemes. It is therefore rather surprising to find that practically all writers on the subject of the phonemes of English decide that this answer is not correct, and that the sound AY in 'which', 'why', etc., is not a phoneme of English but is a realization of a sequence of two phonemes, h and w. We do not need to worry much about this problem in describing the BBC accent. However, it should be noted that in the analysis of the many accents of English that do have a "voiceless w" there is not much more theoretical justification for treating the sound as h plus w than there is for treating p as h plus b. Whether the question of this sound is approached phonetically or phonologically, there is no h sound in the "voiceless w".

A very similar case is the sound found at the beginning of words such as 'huge', 'human', 'hue'. Phonetically this sound is a voiceless palatal fricative (for which the phonetic symbol is ç); there is no glottal fricative at the beginning of 'huge', etc. However, it is usual to treat this sound as h plus j (the latter is another consonant, it is the sound at the beginning of 'yes', 'yet'). Again we can see that a phonemic analysis does not necessarily have to be exactly in line with phonetic facts. If we were to say that these two sounds M, ç were phonemes of English, we would have two extra phonemes that do not occur very frequently. We will follow the usual practice of transcribing the sound at the beginning of 'huge', etc., as hj just because it is convenient and common practice.

|

|

|

|

دراسة: حفنة من الجوز يوميا تحميك من سرطان القولون

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تنشيط أول مفاعل ملح منصهر يستعمل الثوريوم في العالم.. سباق "الأرنب والسلحفاة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تكرّم الفائزين بمسابقة فنِّ الخطابة الثامنة

|

|

|