Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Suprasegmentals

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P21-C1

2025-02-25

688

Suprasegmentals

In the context of utterances, certain features such as pitch, stress, and length are contributing factors to the messages. Such features, which are used simultaneously with units larger than segments, are called ‘suprasegmentals’.

Pitch: The pitch of the voice refers to the frequency of the vocal cord vibration. It is influenced by the tension of the vocal cords and the amount of air that passes through them. In an utterance, different portions are produced at different pitches. The patterns of rises and falls (pitch variation) across a stretch of speech such as a sentence is called its intonation. The meaning of a sentence may depend on its intonation pattern. For example, if we utter the sequence her uncle is coming next week with a falling pitch, this will be interpreted as a statement. If, on the other hand, the same is uttered with a rise in pitch at the end, it will be understood as a question.

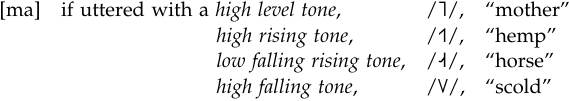

In many languages, the pitch variation can signal differences in word meaning. Such languages, exemplified by several Sino-Tibetan languages (e.g. Mandarin, Cantonese), Niger-Congo languages (e.g. Zulu, Yoruba, Igbo), and many Amerindian languages (e.g. Apache, Navajo, Kiowa), are called tone languages. To demonstrate how tone can affect the lexical change, we can refer to the much-celebrated example of [ma] of Mandarin Chinese:

Such lexical changes cannot be accomplished in non-tonal languages such as English, Spanish, French, etc. In addition to the lexical differences, which are standard in all tone languages, some languages may utilize tonal shifts for morphological or syntactic purposes (e.g. Bini of Nigeria for tense shift, Shona of Zimbabwe to separate the main clause and the relative clause, and Igbo of Nigeria to indicate possession).

Stress: Stress can be defined as syllable prominence. The prominence of a stressed syllable over an unstressed one may be due to a number of factors.

These may include (a) loudness (stressed syllables are louder than unstressed syllables), (b) duration (stressed syllables are longer than unstressed syllables), and (c) pitch (stressed syllables are produced with higher pitch than unstressed syllables). Languages and dialects (varieties) vary in which of these features are decisive in separating stressed syllables from the unstressed ones. In English, higher pitch has been shown to be the most influential perceptual cue in this respect (Fry 1955, 1979).

Variation in syllable duration and loudness produce differences in rhythm. English rhythm (like that of most other Germanic languages) is said to be stress-timed. What this means is that stressed syllables tend to occur at roughly equal intervals in time (isochronous). The opposite pattern, which is known as syllable-timing, is the rhythmic beat by the recurrences of syllables, not stresses. Spanish, Greek, French, Hindi, Italian, and Turkish are good examples of such a rhythm. One of the significant differences between the two types of languages lies in the differences of length between stressed and unstressed syllables, and vowel reduction or lack thereof. We can exemplify this by looking at English and Spanish. If we consider the English word probability and its cognate Spanish probabilidad, the difference becomes rather obvious. Although the words share the same meaning and the same number of syllables, the similarities do not go beyond that. In Spanish (a syllable-timed language), the stress is on the last syllable, [proßaßiliðáð]. Although the remaining syllables are unstressed, they all have full vowels, and the duration of all five syllables is approximately the same. In English (a stress-timed language), on the other hand, the word [pɹ̣àbəbíləɾi] reveals a rather different picture. The third syllable receives the main stress (the most prominent) and the first syllable has a secondary stress (second most prominent). The first, third, and last syllables have full vowels, while the second and fourth syllables have reduced vowels. Thus, besides the two stressed syllables, the last syllable, because it has a full vowel, has greater duration than the second and fourth syllables. Because of such differences in rhythm, English is said to have a ‘galloping’ rhythm as opposed to the ‘staccato’ rhythm of Spanish.

Several scholars (Dauer 1983; Giegerich 1992) object to the binary split between ‘stress-timing’ and ‘syllable-timing’, and suggest a continuum in which a given language may be placed. For example, while French is frequently cited among ‘syllable-timed’ languages, it is also shown to have strong stresses breaking the rhythm of the sentence, a characteristic that is normally reserved for ‘stress-timed’ languages.

A rather uncontroversial split among languages with respect to stress relates to ‘fixed’ (predictable) stress versus ‘variable’ stress languages. In English, as in other Germanic languages, the position of stress is variable. For example, import as a noun will have the stress on the first syllable, [ímpɔɹt], whereas it will be on the second syllable if it is a verb, [ɪmpɔ́ɹt].

In several languages, however, stress is fixed in a given word position. In such cases, the first syllable (e.g. Czech, Slovak, Hungarian, Finnish), the last syllable (e.g. French, Farsi), or the next-to-last syllable (e.g. Polish, Welsh, Swahili, Quechua, Italian) is favored.

Length: Length differences in vowels or consonants may be used to make lexical distinctions in languages. Swedish, Estonian, Finnish, Arabic, Japanese, and Danish can be cited for vowel length contrasts (e.g. Danish [vilə] “wild” vs. [vi:lə] “rest”). English does not have such meaning differences entirely based on vowel length. Examples such as beat vs. bit and pool vs. pull are separated not simply on the basis of length, but also on vowel height and tense/lax distinctions.

In consonantal length, we again make reference to languages other than English. For example, in Italian and in Turkish different consonant length is responsible for lexical distinctions (e.g. Italian nonno [nɔnno] “grandfather” vs. nono [nɔno] “ninth”; Turkish eli [εli] “his/her hand” vs. elli [εlli] “fifty”). In English, we can have a longer consonant at word or morpheme boundaries: [k] black cat, [f] half full, and [n] ten names are produced with one long obstruction.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)