تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

Primes

المؤلف:

Tony Crilly

المصدر:

50 mathematical ideas you really need to know

الجزء والصفحة:

50-54

27-2-2016

2090

Mathematics is such a massive subject, criss-crossing all avenues of human enterprise, that at times it can appear overwhelming. Occasionally we have to go back to basics. This invariably means a return to the counting numbers, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, . . . Can we get more basic than this?

Well, 4 = 2 × 2 and so we can break it down into primary components. Can we break up any other numbers? Indeed, here are some more: 6 = 2 × 3, 8 = 2 × 2 × 2, 9 = 3 × 3, 10 = 2 × 5, 12 = 2 × 2 × 3. These are composite numbers for they are built up from the very basic ones 2, 3, 5, 7, . . . The ‘unbreakable numbers’ are the numbers 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, . . . These are the prime numbers, or simply primes. A prime is a number which is only divisible by 1 and itself. You might wonder then if 1 itself is a prime number. According to this definition it should be, and indeed many prominent mathematicians in the past have treated 1 as a prime, but modern mathematicians start their primes with 2. This enables theorems to be elegantly stated. For us, too, the number 2 is the first prime.

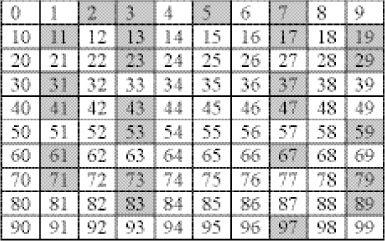

For the first few counting numbers, we can underline the primes: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, . . . Studying prime numbers takes us back to the very basics of the basics. Prime numbers are important because they are the ‘atoms’ of mathematics. Like the basic chemical elements from which all other chemical compounds are derived, prime numbers can be built up to make mathematical compounds.

The mathematical result which consolidates all this has the grand name of the ‘prime-number decomposition theorem’. This says that every whole number greater than 1 can be written by multiplying prime numbers in exactly one way. We saw that 12 = 2 × 2 × 3 and there is no other way of doing it with prime components. This is often written in the power notation: 12 = 22 × 3. As another example, 6,545,448 can be written, 23 × 35 × 7 × 13 × 37.

Discovering primes

Unhappily there are no set formulae for identifying primes, and there seems to be no pattern in their appearances among the whole numbers. One of the first methods for finding them was developed by a younger contemporary of Archimedes who spent much of his life in Athens, Erastosthenes of Cyrene. His precise calculation of the length of the equator was much admired in his own time. Today he’s noted for his sieve for finding prime numbers. Erastosthenes imagined the counting numbers stretched out before him. He underlined 2 and struck out all multiples of 2. He then moved to 3, underlined it and struck out all multiples of 3. Continuing in this way, he sieved out all the composites. The underlined numbers left behind in the sieve were the primes.

So we can predict primes, but how do we decide whether a given number is a prime or not? How about 19,071 or 19,073? Except for the primes 2 and 5, a prime number must end in a 1, 3, 7 or 9 but this requirement is not enough to make that number a prime. It is difficult to know whether a large number ending in 1, 3, 7 or 9 is a prime or not without trying possible factors. By the way, 19,071 = 32 × 13 × 163 is not a prime, but 19,073 is.

Another challenge has been to discover any patterns in the distribution of the primes. Let’s see how many primes there are in each segment of 100 between 1 and 1000.

In 1792, when only 15 years old, Carl Friedrich Gauss suggested a formula P(n) for estimating the number of prime numbers less than a given number n (this is now called the prime number theorem). For n = 1000 the formula gives the approximate value of 172. The actual number of primes, 168, is less than this estimate. It had always been assumed this was the case for any value of n, but the primes often have surprises in store and it has been shown that for n = 10371 (a huge number written long hand as a 1 with 371 trailing 0s) the actual number of primes exceeds the estimate. In fact, in some regions of the counting numbers the difference between the estimate and the actual number oscillates between less and excess.

How many?

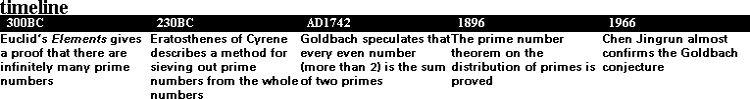

There are infinitely many prime numbers. Euclid stated in his Elements (Book 9, Proposition 20) that ‘prime numbers are more than any assigned multitude of prime numbers’. Euclid’s beautiful proof goes like this:

Suppose that P is the largest prime, and consider the number N = (2 × 3 × 5 × . . . × P) + 1. Either N is prime or it is not. If N is prime we have produced a prime greater than P which is a contradiction to our supposition. If N is not a prime it must be divisible by some prime, say p, which is one of 2, 3, 5, . . ., P. This means that p divides N – (2 × 3 × 5 × . . . × P). But this number is equal to 1 and so p divides 1. This cannot be since all primes are greater than 1. Thus, whatever the nature of N, we arrive at a contradiction. Our original assumption of there being a largest prime P is therefore false. Conclusion: the number of primes is limitless.

Though primes ‘stretch to infinity’ this fact has not prevented people striving to find the largest known prime. One which has held the record recently is the enormous Mersenne prime 224036583 − 1, which is approximately 107235732 or a number starting with 1 followed by 7,235,732 trailing zeroes.

The unknown

Outstanding unknown areas concerning primes are the ‘Twin primes problem’ and the famous ‘Goldbach conjecture’.

Twin primes are pairs of consecutive primes separated only by an even number. The twin primes in the range from 1 to 100 are 3, 5; 5, 7; 11, 13; 17, 19; 29, 31; 41, 43; 59, 61; 71, 73. On the numerical front, it is known there are 27,412,679 twins less than 1010. This means the even numbers with twins, like 12 (having twins 11, 13), constitute only 0.274% of the numbers in this range. Are there an infinite number of twin primes? It would be curious if there were not, but no one has so far been able write down a proof of this.

Christian Goldbach conjectured that:

Every even number greater than 2 is the sum of two prime numbers.

The number of the numerologist

One of the most challenging areas of number theory concerns ‘Waring’s problem’. In 1770 Edward Waring, a professor at Cambridge, posed problems involving writing whole numbers as the addition of powers. In this setting the magic arts of numerology meet the clinical science of mathematics in the shape of primes, sums of squares and sums of cubes. In numerology, take the unrivalled cult number 666, the ‘number of the beast’ in the biblical book of Revelation, and which has some unexpected properties. It is the sum of the squares of the first 7 primes:

666 = 22 + 32 + 52 + 72+ 112 + 132 + 172

Numerologists will also be keen to point out that it is the sum of palindromic cubes and, if that is not enough, the keystone 63 in the centre is shorthand for 6 × 6 × 6:

666 = 13 + 23 + 33 + 43 + 53 + 63 + 53 + 43 + 33 + 23 + 13

The number 666 is truly the ‘number of the numerologist’.

For instance, 42 is an even number and we can write it as 5 + 37. The fact that we can also write it as 11 + 31, 13 + 29 or 19 + 23 is beside the point – all we need is one way. The conjecture is true for a huge range of numbers – but it has never been proved in general. However, progress has been made, and some have a feeling that a proof is not far off. The Chinese mathematician Chen Jingrun made a great step. His theorem states that every sufficiently large even number can be written as the sum of two primes or the sum of a prime and a semi-prime (a number which is the multiplication of two primes).

The great number theorist Pierre de Fermat proved that primes of the form 4k + 1 are expressible as the sum of two squares in exactly one way (e.g. 17 = 12+ 42), while those of the form 4k + 3 (like 19) cannot be written as the sum of two squares at all. Joseph Lagrange also proved a famous mathematical theorem about square powers: every positive whole number is the sum of four squares. So, for example, 19 = 12 + 12 + 12 + 42. Higher powers have been explored and books filled with theorems, but many problems remain.

We described the prime numbers as the ‘atoms of mathematics’. But ‘surely,’ you might say, ‘physicists have gone beyond atoms to even more fundamental units, like quarks. Has mathematics stood still?’ If we limit ourselves to the counting numbers, 5 is a prime number and will always be so. But Gauss made a far-reaching discovery, that for some primes, like 5, 5 = (1 – 2i) × (1 + 2i) where  of the imaginary number system. As the product of two Gaussian integers, 5 and numbers like it are not as unbreakable as was once supposed.

of the imaginary number system. As the product of two Gaussian integers, 5 and numbers like it are not as unbreakable as was once supposed.

the condensed idea

The atoms of mathematics

الاكثر قراءة في هل تعلم

الاكثر قراءة في هل تعلم

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)