An overview of protein isolation

Isolating a protein may be compared to playing a game of golf. In golf, the player is faced with a series of problems, each unique and yet similar to problems previously encountered. In facing each problem the player must analyse the situation and decide, from experience, which club is likely to give the best result in the given circumstances. Similarly, in attempting to isolate proteins, researchers face a series of similar-yet-unique problems. To solve these they must dip into their bags and select an appropriate technique. The purpose of this book is thus to fill the beginnerís “golf bag” with techniques relevant to protein isolation, hopefully to improve their game.

Developing protein isolation is also somewhat like finding a route up a mountainside. Different routes have to be explored and base-camps established at each stage. Occasionally it will be necessary to return to the base of the mountain for further supplies, and haul these up to the established camps, before the next stage can be attacked. A successful climb is always rewarding and if an efficient route is established, it may become a pass, opening the way to further discoveries.

1.1 Why do it?

This book is about the methods that biochemists use to isolate proteins, and so it may be asked, “why isolate proteins?” Looked at in one way, living organisms may be regarded as machines with features in common with the entities that we commonly think of as “machines”. A typical machine is made of a number of parts which interact, transduce energy, and bring about some desired effect. Mechanical machines have moving parts, while electronic machines move electrons. “Engines” convert energy to mechanical motion. Internal combustion engines, for example, convert chemical energy to mechanical motion. Similarly, living organisms such as the human body are complex machines made up of many interacting systems. Proteins constitute the majority of the working parts of these systems and there are thus diverse reasons for isolating proteins, viz.;

• To gain insight. As with any mechanism, to study the way in which a living system works it is necessary to dismantle the machine and to isolate the component parts so that they may be studied, separately and in their interaction with other parts. The knowledge that is gained in this way may be put to practical use, for example, in the design of medicines, diagnostics, pesticides, or industrial processes. Many proteins may themselves be used as “medicines” to make up for losses or inadequate synthesis. Examples are hormones, such as insulin, which is used in the therapy of diabetes, and blood fractions, such as the so-called Factor VIII, which is used in the therapy of haemophilia. Other proteins may be used in medical diagnostics, an example being the enzymes glucose oxidase and peroxidase, which are used to measure glucose levels in biological fluids, such as blood and urine.

• For use in Industry. Many enzymes are used in industrial processes, especially where the materials being processed are of biological origin. In every case a pure protein is desirable as impurities may either be misleading, dangerous or unproductive, respectively. Protein isolation is, therefore, a very common, almost central, procedure in biochemistry.

1.2 Properties of proteins that influence the methods used in their study

It must be appreciated that proteins have two properties which determine the overall approach to protein isolation and make this different from the approach used to isolate small natural molecules.

• Proteins are labile. As molecules go, proteins are relatively large and delicate and their shape is easily changed, a process called denaturation, which leads to loss of their biological activity. This means that only mild procedures can be used and techniques such as boiling and distillation, which are commonly used in organic chemistry, are thus verboten.

• Proteins are similar to one another. All proteins are composed of essentially the same amino acids and differ only in the proportions and sequence of their amino acids, and in the 3-D folding of the amino acid chains. Consequently processes with a high discriminating potential are needed to separate proteins.

The combined requirement for delicateness yet high discrimination means that, in a word, protein separation techniques have to be very subtle. Subtlety, in fact, is required of both techniques and of experimenters in biochemistry.

1.3 The conceptual basis of protein isolation

In a protein isolation one is endeavouring to purify a particular protein, from some biological (cellular) material, or from a bio product, since proteins are only synthesized by living systems. The objective is to separate the protein of interest from all non-protein material and all other proteins which occur in the same material. Removing the other proteins is the difficult part because, as noted above, all proteins are similar in their gross properties. In an ideal case, where one was able to remove the contaminating proteins, without any loss of the protein of interest, clearly the total amount of protein would decrease while the activity (which defines the particular protein of interest) would remain the same (Fig. 1 .).

Figure 1. A schematic representation of protein isolation.

Initially (Fig. 1A) there is a small amount of the desired protein “a” and a large amount of total protein “b”. In the course of the isolation, ìbî is reduced and ultimately (Fig. 1B) only ìaî remains, at which point “a”=“b”. Ideally, the amount of “a” remains unchanged but, in practice, this is seldom achieved and less than 100% recovery of purified protein is usually obtained.

As a general principle, one should aim to achieve the isolation of a protein;-

• in as few steps as possible and,

• in as short a time as possible.

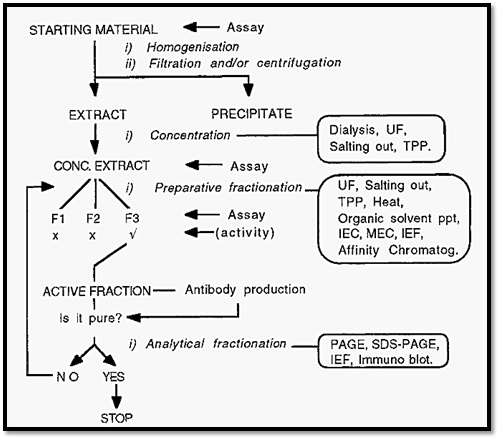

This minimizes losses and the generation of isolation artifacts. Also, to further study the protein, the isolation will have to be done many times over and the effort put into devising a quick, simple, isolation procedure will be repaid many times over, in subsequent savings. The overall approach to the isolation of a protein is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. An overview of protein isolation.

1.3.1 Where to start?

To isolate a protein, one must start with some way of measuring the presence of the protein and of distinguishing it from all other proteins that might be present in the same material. This is achieved by a method which measures (assays) the unique activity of the protein. With such an assay, likely materials can be analyzed in order to select one containing a large amount of the protein of interest, for use as the starting material. Having selected a source material, it is necessary to extract the protein into a soluble form suitable for manipulation. This may be achieved by homogenizing the material in a buffer of low osmotic strength (the low osmotic pressure helps to lyse cells and organelles), and clarifying the extract by filtration and/or centrifugation steps.

The clarified extract is typically subjected to preparative fractionation, at this stage usually by salting out as this also usefully serves to separate protein from non-protein material. It is necessary to assay the fractions obtained, in order to select the fraction(s) containing the protein of interest. The selected fraction(s) can then be subjected to further preparative fractionation, as required, until a pure fraction is obtained.

Experience has shown that there is an optimal sequence in which preparative methods may be applied. As a first approach it is best to apply salting out (or TPP) early in the procedure, followed by ion-exchange or affinity chromatography. Salting out can, with advantage, be followed by hydrophobic interaction chromatography, because hydrophobic interactions are favoured by high salt concentration, so desalting is obviated. The precipitate obtained from TPP, however, is low in salt and so can be applied directly to an ion-exchange system, without prior desalting. Generally, molecular exclusion chromatography should be reserved for late in the isolation when only a few components remain, since it is not a highly discriminating technique. Affinity chromatography often achieves the desirable aims of a rapid isolation using a minimum number of steps and so it should always be explored and preferentially used where possible.

1.3.2 When to stop?

How can one know when the fraction is pure, i.e. when to stop? To obtain this information it is necessary to analyse the isolated fraction using a number of analytical fractionation methods. If a number of such analytical methods reveal the apparent presence of only one protein, it may be inferred that the protein is pure, and that the isolation has been successfully completed. Note, however, that it is not possible to prove that the protein is pure; one can merely fail to demonstrate the presence of impurities. Future, improved, analytical methods may reveal impurities that are not detected using current technology.

If, on the other hand, any analytical fractionation method demonstrates the presence of more than one protein, it may be inferred that the preparation is not pure. In this case, the application of further preparative fractionation methods may be required before the protein is finally purified.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the requirement is to remove as much contaminating protein as possible, while retaining as much as possible of the desired protein. Clearly then, to monitor the progress of an isolation, one needs two assays, one for the activity of the protein of interest (expressed in units of activity/ml) and another for the protein content (expressed as mg/ml). The activity per unit of protein (units/mg) gives a measure of the so-called specific activity. In the course of a successful protein isolation, the specific activity should increase with each step, reaching a maximum value when the protein is pure. It is also desirable that a maximum yield of the protein is obtained. The protein of interest is defined by its activity and so information concerning the yield may also be obtained from activity assays.

1.4 The purification table

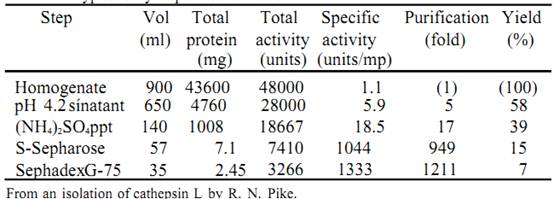

The results of activity and protein assays, from a protein purification, are typically summarized in a so called purification table, of which Table 1 is an example.

Table 1. A typical enzyme purification table

The figures in Table 1 are arrived at as follows:- Volume (ml) this refers to the measured total solution volume at the particular stage in the isolation.

• Total protein (mg) - the primary measurement is of protein concentration, i.e. mg ml-1, which is obtained using a protein assay. Multiplying the protein concentration by the total volume gives the total protein (i.e. mg/ml x ml = mg).

• Total activity (units) the activity, in units ml-1, is obtained from an activity assay. Multiplying the activity by the total volume gives the total activity (i.e. units/ml x ml = units).

• Specific-activity (units/mg) - the specific activity is obtained by dividing the total activity by the total protein. Alternatively, the activity (units/ml) can be divided by the protein concentration (mg/ml), in which case the miles cancel out, leaving units/mg.

• Purification (fold)

fold refers to the number of multiples of a starting value. In this case it refers to the increase in the specific activity, i.e. the purification is obtained by dividing the specific activity at any stage by the specific activity of the original homogenate. The purification “per step” can also be obtained by dividing the specific activity after that step by the specific activity of the material before that step.

• Yield (%) - the yield is based on the recovery of the activity after each

step. The activity of the original homogenate is arbitrarily set at 100%. The yield (%) is calculated from the total activity (units) at each step divided by the total activity (units) in the homogenate, multiplied by 100. The yield can also be calculated on a “per step” basis by dividing the total activity after that step by the total activity before that step and multiplying by 100.

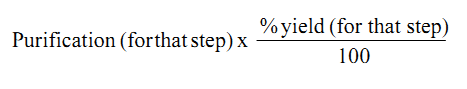

The efficiency of a step - is calculated as:-

References

Dennison, C. (2002). A guide to protein isolation . School of Molecular mid Cellular Biosciences, University of Natal . Kluwer Academic Publishers new york, Boston, Dordrecht, London, Moscow

الاكثر قراءة في عزل البروتين

الاكثر قراءة في عزل البروتين

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة