النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Amplification methods

المؤلف:

Clive Dennison

المصدر:

A guide to protein isolation

الجزء والصفحة:

20-4-2016

4717

Amplification methods

At low levels of Ab and Ag, no visible precipitation may be formed. In modem methods of immunological analysis, therefore, use is made of amplification methods which enable the Ab/Ag reactions to be visualized and quantitated. Amplification methods will be discussed here in more-or-less historical order. the enzyme and immunogold methods being more recent.

1 . Complement fixation

Complement is a name given to a group of serum proteins which bind Ag/Ab complexes and cause lysis of cells displaying surface antigens. Complement thus functions in vivo as part of the immune response, aimed at the lysis of foreign cells. This activity is exploited in the complement fixation assay, which is a sensitive means of detecting Ag/Ab complexes. The complement fixation assay is about 100-fold more sensitive than the precipitin reaction.

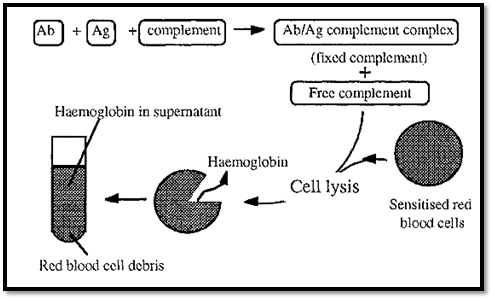

Figure 1. The complement fixation assay.

The complement fixation assay depends on the fact that complement is consumed (fixed) by Ag/Ab complexes, making less complement available. The amount of complement left (i.e. not fixed by the Ag/Ab complexes) can be measured by its ability to lyse red blood cells sensitized by antibodies binding to surface antigens. The amount of lysis can be quantitated by measuring the haemoglobin released into the supernatant, by its absorbance at 541 nm.

If all of the complement was bound by Ag/Ab complexes, none would be available to bind to the red blood cells and no lysis, and consequently no release of haemoglobin, would occur. On the other hand, if no Ag/Ab complexes were formed, no complement would be fixed, so all of it would be available to lyse red blood cells and the absorbance of the released haemoglobin would be at a maximum.

In order to measure the amount of a specific Ag present in a complex mixture, it is necessary to first establish a standard curve by measuring the complement fixed when different amounts of Ag are added to a fixed amount of complement and Ab. The standard curve (Fig. 2) has a shape similar to that of an immunoprecipitation curve.

Because of the shape of the standard curve, two different Ag concentrations can give the same degree of complement fixation (dotted lines in Fig. 2). In measuring an unknown, therefore, it is necessary to test several dilutions of the Ag to establish on which side of the curve the Ag concentration falls. The [Ag] can then be read off from the standard curve.

Figure 2. Standard curve for complement fixation.

The method has two principal disadvantages:-

• Certain crude mixtures cause haemolysis by mechanisms unrelated to complement, and,

• Some crude mixtures inactivate complement in the absence of the appropriate Ag/Ab complex.

2. Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

Radioimmunoassays (RIAs) combine the sensitivity of radioisotope detection with the selectivity of immunoassays. RIAs can be used to detect molecules that do not fix complement when combined with a specific antibody, for example haptens, and RIAs are mostly used for the assay of small molecules. Examples of compounds that can be assayed by RIA are peptide hormones, steroids (such as testosterone), cyclic AMP, morphine, digitalis etc.

The principle of the RIA is the same as that of the chemical assay technique known as an isotope dilution assay. In an isotope dilution assay a known amount of a radioisotope, of known specific activity (i.e radioactivity per unit mass), is added to a sample and a pure sample of the element of interest is subsequently extracted and its specific activity determined. The decrease in the specific activity of the isolated element is due to the presence of the non-radioactive isotope which dilutes the radioactive isotope. From the extent of this dilution, the concentration of the endogenous, non-radioactive isotope can be determined.

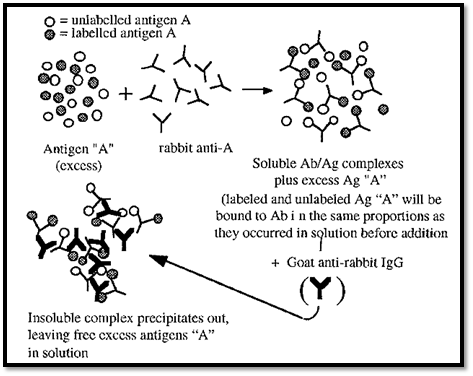

Figure 3. Radioimmunoassay.

A RIA is illustrated in Fig. 3. In a RIA, a radio-labelled antigen is used to dilute an unknown amount of an unlabelled antigen, present in the sample. A non-saturating amount of, say, rabbit antibody to the antigen is added (i.e. the antigen must be in excess). The labelled and unlabelled antigens will bind to the antibodies in the same ratio as they are present in the sample. The Ab/Ag complexes can then be precipitated, for example by addition of a goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody. The radioactivity in the precipitate will be inversely related to the amount of the antigen originally present in the sample. The concentration of the unknown antigen in the sample can thus be measured by reference to a straight line standard curve in which the % inhibition is plotted against log[non-radioactive Ag].

Radioimmunoassay has the following disadvantages:

• A radioactively labelled Ag may not be available, especially for an antigen which has not been extensively studied.

• Associated with the radioimmunoassay are all of the hazards of radioisotopes, which means that specially equipped laboratories and special licenses are necessary.

3 .Enzyme amplification

The advantage of enzyme methods over radioisotope methods of amplification is that, because enzymes are safe and biodegradable, no special licences or safety facilities are required, and disposal after use is no problem.

3.1 Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The ELISA method was introduced in its modern form by Engvall and Perlmann and van Weemen and Schuurs. The principle of an ELISA is that an enzyme, linked to an immunoreactive molecule (an antibody or protein A) can be used to detect the presence of an antigen with great sensitivity, due to the amplification achieved by the enzyme catalyzed reaction. The method can also be turned about and used to detect Ab. Several different formats of ELISA are possible. Only some concepts pertaining to ELISAs are discussed here. For details on how to conduct an ELISA, a specialist text should be consulted.

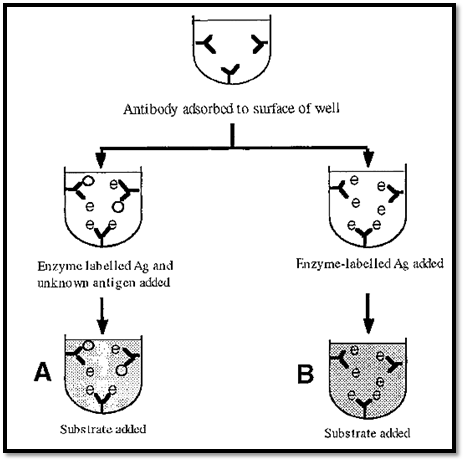

The competitive ELISA for measurement of Ag is conceptually similar to a RIA, in that a labelled Ag competes with an unlabelled Ag for binding to the antibody, but in this case the label is an enzyme (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. A competitive ELISA for measuring [Ag]. Unknown [Ag] is proportional to the absorbance difference between the wells A and B.

Antibody is immobilized by adsorption onto the walls of a plastic microtitre plate. Excess antibody is washed off and the enzyme-linked Ag is added to one set of wells while the unknown sample, mixed with enzyme-linked Ag is added to another set. The unknown sample Ag thus serves to dilute the amount of labelled Ag which reacts with the immobilized Ab After incubation, excess antigen is washed off and a solution of the enzyme substrate is added. The enzyme catalyzed reaction generates a colour which can be measured. The intensity of this colour is inversely proportional to the amount of Ag originally present. The microtitre plate contains 96 wells in an 8 x 12 array, which permits the exploration of a number of different combinations of coating and Ab/Ag concentrations, permitting optimization of the reaction.

In another format, related to immunoblotting , the Ag (usually a solution containing a mixture of proteins, including the protein of interest) may be adsorbed onto the walls of a microliter plate and the Ag of interest subsequently detected with an enzyme-labelled Ab. For increased sensitivity, further amplification may be obtained by using two antibodies, an Ag-specific primary Ab and an enzyme-labeled secondary Ab that is specific for the type of primary Ab. This has the advantage that the secondary enzyme-labeled secondary Ab can be a universal reagent, targeting primary Abs of the same type but with different specificities.

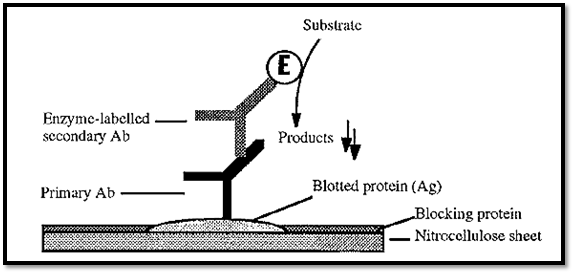

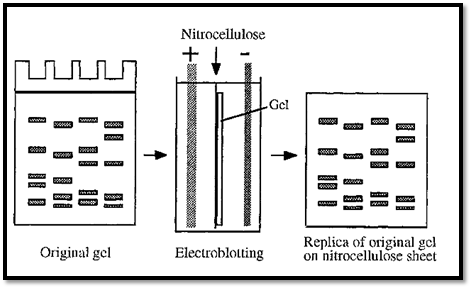

3.2 Immunoblotting

In one ELISA format the principle of amplified detection of an immobilized Ag using an enzyme labeled Ab is used. The Ag, in this case, may be coated onto the walls of a microtitre plate. A similar principle applies to immunoblotting, whereby Ag immobilised on for e.g. a nitrocellulose filter, can be detected using an enzyme-linked antibody system (Fig. 5). An example is dot blotting, in which a small volume of the antigen of interest is dotted onto a nitrocellulose filter. The surrounding protein-binding sites may be blocked with milk proteins, which do not tend to bind proteins non-specifically. The dot can then be probed with a primary antibody, followed by an enzyme-labelled secondary antibody, as in an ELISA. The only difference is that in an ELISA, the enzyme product is soluble, whereas in an immunoblotting an insoluble product is necessary. A commonly used combination is horseradish peroxidase as the enzyme label, with 4-chloro- l-naphthol as the substrate. The blue/grey product is insoluble in water. Alternatively, a gold-labelled Ab or protein A may be used.

Figure 5. A schematic sketch of immunoblotting.

A related technique is western blotting. The curious name of this technique is due to a pun. A technique for the blotting of DNA fragments, and probing these with labelled RNA, was named Southern blotting after its originator, E. M. Southern. The reverse process:

blotting RNA and probing this with DNA fragments, was then named northern blotting, to indicate that it was an opposite process. The blotting of proteins was subsequently called “western blotting” to indicate a similar process but with different molecules, i.e. in a different direction. In western blotting, proteins are first separated by SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins are then drawn out of the gel, and blotted onto nitrocellulose, by transverse electrophoresis, forming a replica of the gel separation (Fig. 6). In this process the nitrocellulose sheet must be on the anodic side of the gel, as protein/SDS complexes are negatively charged and have an anodic migration.

Within the gel the proteins are not accessible to probing by antibodies, but they become accessible after electroblotting onto the surface of a nitrocellulose sheet. Antibodies bound to the blotted proteins can be detected with an enzyme-labelled secondary antibody, as in a dot blot.

Figure 6. Electroblotting.

Treatment with SDS tends to denature proteins, although the effects can be minimized if the sample is not boiled in SDS. The denatured protein might not be recognized by the antibodies used to probe the blot. In this case a renaturing blot system, can be used to advantage. In this technique the transfer buffer does not contain SDS and the SDS may be removed from the gel before the transfer step. The nitrocellulose sheet must be placed on the appropriate side of the gel, depending on the direction of migration of the protein at the pH of the transfer buffer. Normally a high pH is used, giving an anodic migration, but this is not appropriate if the protein is not stable at a high pH.

In a gel of constant composition, proteins separate by virtue of their differential rates of migration, smaller proteins migrating faster than large ones. This same differential will apply to the migration of proteins during the transfer step, i.e. smaller proteins will transfer to the nitrocellulose more rapidly. If insufficient time is allowed for the transfer, the blot will be biased in favour of smaller proteins. This effect can be overcome by running the first electrophoresis in a gradient gel. In this case the proteins will each reach a point in the gradient where they are about equally impeded by the gel and during the lateral transfer step they will all migrate out of the gel at about the same rate.

Western blotting is useful for determining the presence or absence of a specific Ag in a complex mixture. It is also useful for testing the specificity of an Ab, before this is used in immunocytochemistry, for example. Blotting (not immunoblotting) is also used as a step in the sequencing of a protein band purified by gel electrophoresis. For this purpose the protein is electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, the blot excised and transferred into the sequenator.

4 .Immunogold labeling with silver amplification

Colloidal gold particles, ranging in diameter from 1 to 30 nm, can be prepared by reducing dissolved gold chlorides with various reducing agents . Proteins bind readily to such particles and stabilize the colloids against a salt challenge. Colloidal gold particles can thus be used as labels, attached to either antibodies or protein A, to form immunogold probes. Such immunogold probes find their greatest use in electron microscopy immunocytochemistry, whereby the subcellular distribution of an Ag of interest may be determined. Colloidal gold particles are very electron dense and show up readily in electron micrographs.

With silver amplification, immunogold probes may also be used at the light microscopy level and for staining immunoblots. In the immunogold-with-silver-amplification (IGSS) technique, the colloidal gold label serves as a nucleation center for the deposition of metallic silver. This yields a black stain which marks the position of the Ag of interest.

5 . Colloid agglutination

As mentioned above , proteins can stabilize colloids. The proteins bind to the colloidal particles and similar charge repulsion between the bound proteins keeps the colloidal particles apart, thus preventing flocculaton. Latex beads are commonly used as colloidal suspensions for analysis. A natural system, which is virtually colloidal, is blood, in which the red cells are prevented from aggregating by virtue of their similar surface charges.

Antibodies are divalent and are thus able to simultaneously bind to two similar antigens on two different colloidal particles. Such cross-linking of the colloidal particles causes them to flocculate out of suspension, and this provides a very sensitive method for the detection of Abs specific for the colloid-bound Ag. The method is particularly useful for medical diagnosis in the field. Since flocculation can easily be detected by eye, no sophisticated instrumentation is required. The method gives a simple yes-or-no answer, but it can be made semi-quantitative by dilution of the Ab, until the “definite yes” becomes a “maybe”. The dilution at which this happens is inversely related to the initial antibody concentration.

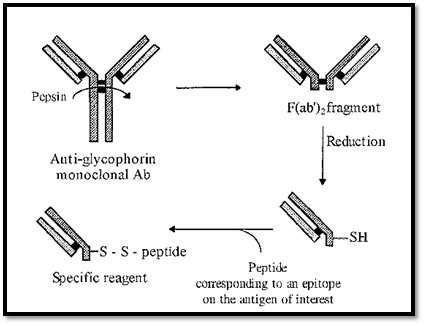

An elegant diagnostic method uses agglutination of endogenous red blood cells as the reporter system. Monoclonal Abs are raised against glycophorin, a glycoprotein present on the surface of all red blood cells. These Abs are species specific, i.e. they only recognize glycophorin from a particular species. From these monoclonal Abs, F(ab’), fragments can be made by proteolysis with pepsin. F(ab’)2 fragments consist of the two Fab arms of the Ab, bound together by disulfide bridges. The presence of the disulfide bridges is useful as these can be reduced and subsequently used to conjugate a peptide epitope to the free -SH groups of the two separate Fab fragments. This generates a specific diagnostic reagent (Fig. 7).

Addition of this reagent to a drop of blood will cause haemagglutination, if Abs targeting the peptide epitope are present. For example, a person infected with the AIDS virus will, in the early stages, have anti-AIDS virus Abs present in their blood. These Abs will target specific epitopes on the AIDS virus proteins. These epitopes can be identified and corresponding peptides can be synthesized. Conjugation of one such peptide to an anti-human glycophorin monoclonal Ab half-F(ab’)2 fragment will generate a specific diagnostic reagent. Addition of an appropriate dilution of this reagent to a drop of a patient’s blood will give a yes/no indication of the presence of anti-AIDS virus Abs in the patients blood. A positive answer is given by the agglutination of the red blood cells. Such diagnostic analyses are useful for screening in the field but they should be followed by confirmatory laboratory-based tests, such as ELISA

Figure 7. Generation of a reagent for detecting the presence of specific antibodies, using endogenous red blood cells as the reporter system.

References

Dennison, C. (2002). A guide to protein isolation . School of Molecular mid Cellular Biosciences, University of Natal . Kluwer Academic Publishers new york, Boston, Dordrecht, London, Moscow .

Engvall, E. and Perlmann, P. (1 971) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry 8, 871 -879.

van Weemen, B. K. and Schuurs, A. H. W. M. (1971) Immunoassay using antigen- enzyme conjugates. FEBS Letters 15, 232-236.

Tijssen, P. (1 985) Practice and Theory of Immunoassays. in Laboratory Techniques in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Vol 15, (Burdon, R. H. and van Knippenberg, P. H., eds), Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Kemeny, D. M. and Challacombe, S. J. (1988) ELISA and Other Solid Phase Immunoassays. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

Brada, D. and Roth, J. (1984) Golden blot detection of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies bound to antigens on nitrocellulose by protein A-gold complexes. Anal. Biochem. 142, 79-83.

Kerr; M. A. and Thorpe R. (1994) in Immunochemistry Labfax. flios Scientific Publishers, Oxford, pp138-141.

Towbin, H., Staehelin, T. and Gordon, J. (1979) Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 4350-4354.

الاكثر قراءة في عزل البروتين

الاكثر قراءة في عزل البروتين

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)