تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Cosmic synchrotron radiation

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 34

2024-03-26

960

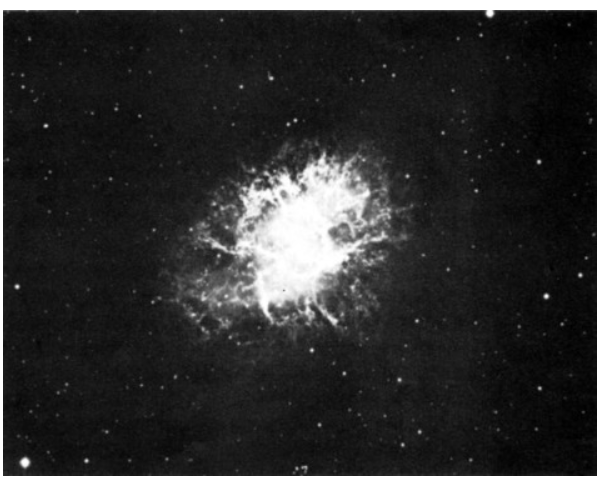

Fig. 34–7. The crab nebula as seen in all colors (no filter).

In the year 1054 the Chinese and Japanese civilizations were among the most advanced in the world; they were conscious of the external universe, and they recorded, most remarkably, an explosive bright star in that year. (It is amazing that none of the European monks, writing all the books of the Middle Ages, even bothered to write that a star exploded in the sky, but they did not.) Today we may take a picture of that star, and what we see is shown in Fig. 34–7. On the outside is a big mass of red filaments, which is produced by the atoms of the thin gas “ringing” at their natural frequencies; this makes a bright line spectrum with different frequencies in it. The red happens in this case to be due to nitrogen. On the other hand, in the central region is a mysterious, fuzzy patch of light in a continuous distribution of frequency, i.e., there are no special frequencies associated with particular atoms. Yet this is not dust “lit up” by nearby stars, which is one way by which one can get a continuous spectrum. We can see stars through it, so it is transparent, but it is emitting light.

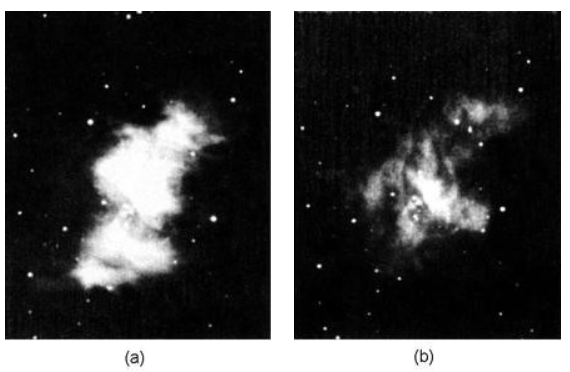

Fig. 34–8. The crab nebula as seen through a blue filter and a polaroid. (a) Electric vector vertical. (b) Electric vector horizontal.

In Fig. 34–8 we look at the same object, using light in a region of the spectrum which has no bright spectral line, so that we see only the central region. But in this case, also, polarizers have been put on the telescope, and the two views correspond to two orientations 90∘ apart. We see that the pictures are different! That is to say, the light is polarized. The reason, presumably, is that there is a local magnetic field, and many very energetic electrons are going around in that magnetic field.

We have just illustrated how the electrons could go around the field in a circle. We can add to this, of course, any uniform motion in the direction of the field, since the force, qv×B, has no component in this direction and, as we have already remarked, the synchrotron radiation is evidently polarized in a direction at right angles to the projection of the magnetic field onto the plane of sight.

Putting these two facts together, we see that in a region where one picture is bright and the other one is black, the light must have its electric field completely polarized in one direction. This means that there is a magnetic field at right angles to this direction, while in other regions, where there is a strong emission in the other picture, the magnetic field must be the other way. If we look carefully at Fig. 34–8, we may notice that there is, roughly speaking, a general set of “lines” that go one way in one picture and at right angles to this in the other. The pictures show a kind of fibrous structure. Presumably, the magnetic field lines will tend to extend relatively long distances in their own direction, and so, presumably, there are long regions of magnetic field with all the electrons spiralling one way, while in another region the field is the other way and the electrons are also spiralling that way.

What keeps the electron energy so high for so long a time? After all, it is 900 years since the explosion—how can they keep going so fast? How they maintain their energy and how this whole thing keeps going is still not thoroughly understood.