Evaporation of a liquid

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 40

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 40

2024-05-23

2024-05-23

1818

1818

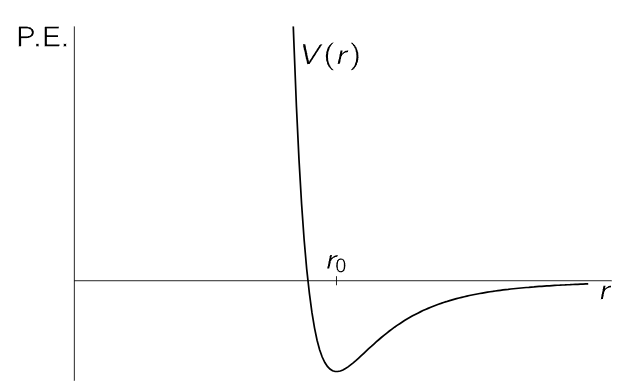

In more advanced statistical mechanics, one tries to solve the following important problem. Consider an assembly of molecules which attract each other, and suppose that the force between any two, say i and j, depends only on their separation rij, and can be represented as the derivative of a potential function V(rij). Figure 40–3 shows a form such a function might have. For r>r0, the energy decreases as the molecules come together, because they attract, and then the energy increases very sharply as they come still closer together, because they repel strongly, which is characteristic of the way molecules behave, roughly speaking.

Fig. 40–3. A potential-energy function for two molecules, which depends only on their separation.

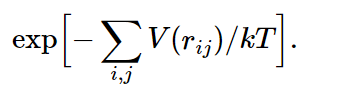

Now suppose we have a whole box full of such molecules, and we would like to know how they arrange themselves on the average. The answer is e−P.E./kT. The total potential energy in this case would be the sum over all the pairs, supposing that the forces are all in pairs (there may be three-body forces in more complicated things, but in electricity, for example, the potential energy is all in pairs). Then the probability for finding molecules in any particular combination of rij’s will be proportional to

Now, if the temperature is very high, so that kT≫|V(r0)|, the exponent is relatively small almost everywhere, and the probability of finding a molecule is almost independent of position. Let us take the case of just two molecules: the e−P.E./kT would be the probability of finding them at various mutual distances r. Clearly, where the potential goes most negative, the probability is largest, and where the potential goes toward infinity, the probability is almost zero, which occurs for very small distances. That means that for such atoms in a gas, there is no chance that they are on top of each other, since they repel so strongly. But there is a greater chance of finding them per unit volume at the point r0 than at any other point. How much greater, depends on the temperature. If the temperature is very large compared with the difference in energy between r=r0 and r=∞, the exponential is always nearly unity. In this case, where the mean kinetic energy (about kT) greatly exceeds the potential energy, the forces do not make much difference. But as the temperature falls, the probability of finding the molecules at the preferred distance r0 gradually increases relative to the probability of finding them elsewhere and, in fact, if kT is much less than |V(r0)|, we have a relatively large positive exponent in that neighborhood. In other words, in a given volume they are much more likely to be at the distance of minimum energy than far apart. As the temperature falls, the atoms fall together, clump in lumps, and reduce to liquids, and solids, and molecules, and as you heat them up they evaporate.

The requirements for the determination of exactly how things evaporate, exactly how things should happen in a given circumstance, involve the following. First, to discover the correct molecular-force law V(r), which must come from something else, quantum mechanics, say, or experiment. But, given the law of force between the molecules, to discover what a billion molecules are going to do merely consists of studying the function e−∑Vij/kT. Surprisingly enough, since it is such a simple function and such an easy idea, given the potential, the labor is enormously complicated; the difficulty is the tremendous number of variables.

In spite of such difficulties, the subject is quite exciting and interesting. It is often called an example of a “many-body problem,” and it really has been a very interesting thing. In that single formula must be contained all the details, for example, about the solidification of gas, or the forms of the crystals that the solid can take, and people have been trying to squeeze it out, but the mathematical difficulties are very great, not in writing the law, but in dealing with so enormous a number of variables.

That then, is the distribution of particles in space. That is the end of classical statistical mechanics, practically speaking, because if we know the forces, we can, in principle, find the distribution in space, and the distribution of velocities is something that we can work out once and for all, and is not something that is different for the different cases. The great problems are in getting particular information out of our formal solution, and that is the main subject of classical statistical mechanics.

الاكثر قراءة في خواص المادة

الاكثر قراءة في خواص المادة

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة