Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Written Syllabification

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P146-C6

2025-03-13

743

Written Syllabification

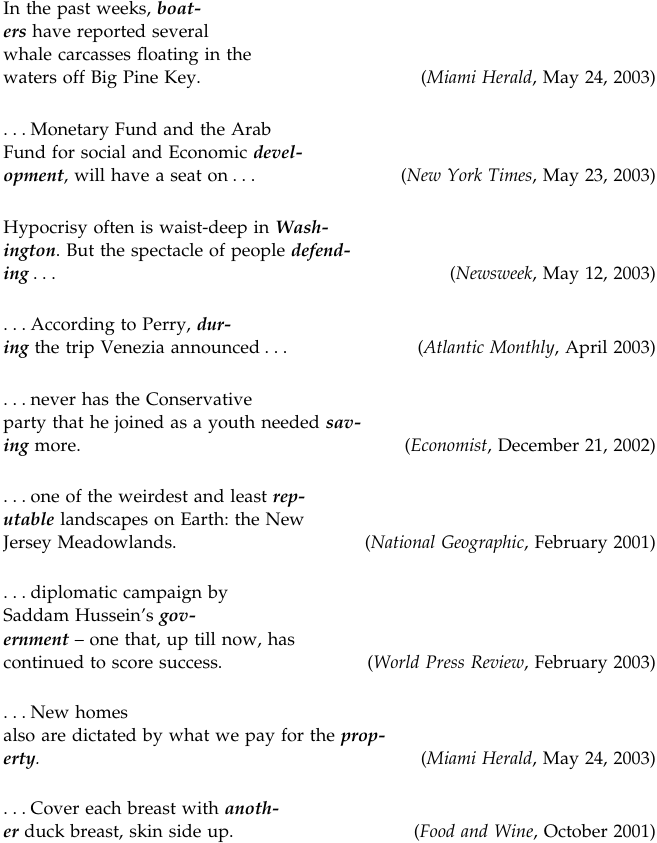

People who wrote term papers, theses, or dissertations before the advent of computers, and thus of word-processing programs, had to deal with the problem of written syllabification frequently because it was not possible to arrange words on a given line ending perfectly at the right margin. Decisions as to where to break the words were not always easy, as the writer could not simply follow the breaks that she or he would make in spoken language. Thus, one had two choices: (a) have a page full of written lines with uneven right-margin appearance, or (b) consult a dictionary and break up the word according to the dictionary suggestions. This appears to be a non-issue today due to the availability of the ‘justified margin’ option in word processors. By the use of this option, we do not have to break any words at the end of a line. If, toward the end of a line, a word is too long or too short, the program either expands or contracts the spacing between letters without causing any breaks. However, as the following examples from printed media demonstrate, the problem is still with us.

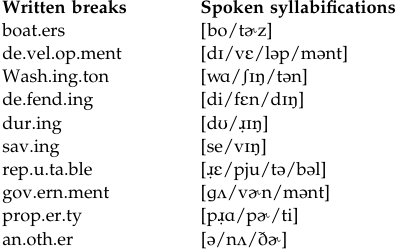

As you might have easily detected, as hundreds of native speakers I have tested have, there are obvious discrepancies between the breaks that are in print and the syllable breaks we use in the spoken language for the words in bold type above and listed below.

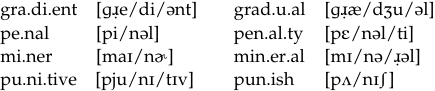

To make matters worse, we find some morphologically related words with the following:

While the native speakers’ spoken syllabifications are in complete agreement with the written breaks suggested by the dictionaries for words in the first column (gradient, penal, miner, and punitive), they are in total disagreement for the words in the third column. We hear [gɹ̣æ/dʒu/əl] (not [gɹ̣ædʒ/u/əl]), [mɪ/nə/ɹ̣əl] (not [mɪn/ɚ/əl]), etc.

What is really unfortunate is that dictionary representations are not simply suggestions for the breaks for written language, but are also claims, in phonetic transcription, for the spoken syllabifications of the words. For this reason, and the reason that this system is taught to elementary schoolchildren, we would like to make the difference very clear and make practitioners aware of the entirely different principles used in written syllabification. This is an important issue, because, several stress rules of English are sensitive to syllable structures, and these are entirely based on spoken syllables and have nothing to do with the conventions of written breaks.

Written syllabification seems to follow two principles:

(a) If a word has prefixes and/or suffixes, these cannot be divided.

(b) If the orthographic letter a, e, i, o, u, or y represents a long or short vowel sound, then the following principles are applied: when one of these letters in the written form stands for a long vowel or a diphthong /i, e, u, o, aɪ, aʊ, ɔɪ/, the next letter representing the consonant in the orthography goes in the following syllable in written language. If, on the other hand, these orthographic letters stand for a short vowel sound, then the next letter goes with the preceding syllable. To verify this, we can look at pairs such as penal– penalty and miner– mineral. In the first word of the first pair, the letter e represents the long vowel /i/ and the written syllabification is pe.nal (which happens to correspond to the spoken syllabification [pi/nəl]). In the second word of the same pair, the same letter e stands for a short vowel, /ε/, and thus the written syllabification is pen.al.ty. Similarly, in the second pair (miner– mineral), the letter i stands for the diphthong /aɪ/ in the first word (hence the syllabification mi.ner, which corresponds to the spoken [maɪ.nɚ]) and for the short vowel /ɪ/ in the second (hence the syllabification min.er.al).

We should also point out that the first principle is the stronger one in that even if the orthographic letter stands for a long vowel or a diphthong, the integrity of a prefix or a suffix is maintained. This will be clear if we look at the word boaters, which is syllabified as boat.ers in the written language. Although the orthographic representation of the first syllable stands for a long vowel in speech, [o], the following letter, t, does not go into the following syllable in the written representation, and the only reason for this is the suffixation that this word has. Similarly, in the word saving, the written break is given as sav.ing, which, despite its total conflict with the spoken version ([se/vɪŋ]), has to follow the integrity of the suffix -ing. For an example of a conflict created by the integrity of a prefix, we can cite the written syllabification of un.able, as opposed to its preferred spoken syllabification [Λ/ne/bəl].

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)