Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Gender systems

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P128-C8

2025-12-29

36

Gender systems

Anon-linguist is likely to assume that the gender of a noun is identical to the gender of the thing it refers to. However, it is easy to find counter examples to this claim. The German word Mädchen ‘girl,’ for example, is grammatically neuter even though it refers to a female human. Such examples show how important it is to distinguish between grammatical gender and “natural” (or biological) gender. Biological gender (male vs. female) relates to reproductive functions and is relevant only to humans, the higher orders of the animal kingdom, and certain plant species. Grammatical gender is a subclassification of nouns based on shared inflectional morphology, and must be specified for every noun in the language.1

Gender classes are determined on the basis of agreement patterns. For example, we know that Mädchen belongs to the neuter class because it requires the neuter form of various determiners and modifiers, e.g. das Mädchen ‘the girl’; compare die Frau ‘the woman’ (feminine), der Mann ‘the man’ (masculine).

Labeling gender classes is a bit like labeling syntactic categories: the classes are set up on the basis of grammatical criteria, but labels are assigned on the basis of semantic features and prototypes. We might use the labels MASCULINE and FEMININE where there is a statis tical correlation between noun class (grammatical gender) and biological gender, or where the prototypical members of two of the classes include male humans and female humans, respectively. But the correlation is never perfect. Since every noun must belong to some gender class, the assignment may seem quite arbitrary in many cases. In Latin, for example, ignis ‘fire’ is masculine, while flamma ‘flame’ is feminine.

The classification of particular nouns may reflect interesting facts about the world view or traditional beliefs of the language group. For example, in Latin ‘sun’ is masculine while ‘moon’ is feminine; but in the Australian language Dyirbal, these genders are reversed. This is because the two cultures have different myths associated with these two heavenly bodies. (In the Dyirbal myth, the sun is a woman and the moon is her husband.) But, partly because languages are always changing, in most gender systems there are some nouns whose classification seems arbitrary or does not follow the basic semantic patterns in the rest of the system.

In a number of languages, gender is partly determined on the basis of phonological or morphological patterns as well as semantic features. Returning to our German example, the word Mädchen ‘girl’ must be grammatically neuter because all nouns which contain the diminutive suffix-chen are grammatically neuter.2 However, we should emphasize the fact that, while there is often a correlation between a noun’s phonological shape and the gender class it belongs to, its class membership should always be identified on the basis of the agreement patterns which the noun triggers. In Portuguese there are some words which end in /-a/ but are grammatically masculine, e.g. o problema ‘the problem’; and a few words which end in /-o/ but are grammatically feminine, e.g. a tribo ‘the tribe.’3 The grammatical gender of these words is indicated by agreement patterns observed in the definite article (o ‘masculine’ vs. a ‘feminine’) and in any modifying adjectives that may be present.

Often there is no correlation between noun class and biological gender. Rather, some other semantic property may form the basis for the grammatical gender system. Isthmus Zapotec has three gender classes based on degrees of animacy: human vs. animal vs. inanimate (see (15) below). In other languages gender classification may correlate with size and shape, edible vs. inedible objects, etc.

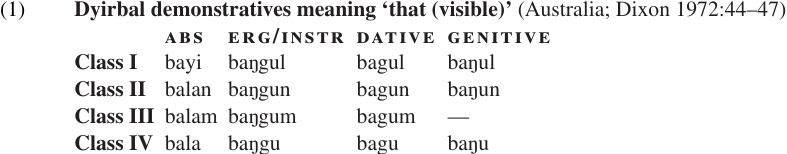

As we saw, Portuguese distinguishes only two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine. German, Russian, and a number of other European languages distinguish three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter). Dyirbal has four genders. The gender of the head noun is indicated by a determiner that also indicates the case of the NP and its proximity to the speaker (‘here,’ ‘there but visible,’ or ‘there and not visible’). The various case and gender forms of the marker that signals ‘there but visible’ are listed in (1).

Examples of the kinds of Dyirbal words which belong to each gender class are listed in (2). Dixon (1972) presents a very interesting analysis of the semantic basis for the gender categories, showing how they relate to the traditional Dyirbal world view; but, as (2) suggests, the patterns are quite complex.

(2) Semantic correlates of Dyirbal gender classes (Dixon 1972:306–311)

Class I human males; moon; rainbow; storms; kangaroos, possums, bats;

most snakes, fishes, insects; some birds (e.g. hawks); boomerangs

Class II human females; sun and stars; anything connected with fire and

water; dogs, platypus, echidna; harmful fish; some snakes; most

birds; most weapons

Class III edible fruits and the trees that bear them; tubers

Class IV body parts, meat, bees and honey, wind, most trees, grass, mud,

stones, etc.

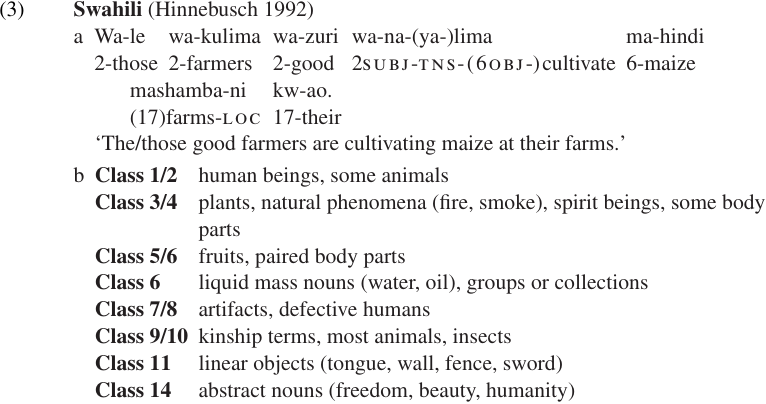

Bantu languages are famous for their noun class systems, which involve not only agreement between nouns and their modifiers but also verbal agreement with subjects and (optionally) direct objects. The pattern is illustrated with a Swahili sentence in (3a). The agreement prefixes signal both noun class and number: class 2 is the plural form of class 1; class 6 the plural form of class 5, etc. Semantic correlates for some of these classes are listed in (3b).

1. See Derivational morphology for the distinction between inflectional and derivational morphology.

2. See Derivational morphology.

3. Bill Merrifield (p.c.) points out that the masculine forms ending in /-a/ tend to be derived from Greek roots.

الاكثر قراءة في Nouns gender

الاكثر قراءة في Nouns gender

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)