النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الحيوية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الحيوية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Mycobacterium

المؤلف:

Fritz H. Kayser

المصدر:

Medical Microbiology -2005

الجزء والصفحة:

6-3-2016

5644

Mycobacterium

Mycobacteria are slender rod bacteria that are stained with special differential stains (Ziehl-Neelsen). Once the staining has taken, they cannot be destined with dilute acids, hence the designation acid-fast. In terms of human disease, the most important mycobacteria are the tuberculosis bacteria (TB) M. tuberculosis and M. bovis and the leprosy pathogen (LB) M. leprae.

TB can be grown on lipid-rich culture mediums. Their generation time is 12-18 hours. Initial droplet infection results in primary tuberculosis, localized mainly in the apices of the lungs. The primary disease develops with the Ghon focus (Ghon's complex), whereby the hilar lymph nodes are involved as well. Ninety percent of primary infection foci remain clinically silent. In 10% of persons infected, primary tuberculosis progresses to the secondary stage (reactivation or organ tuberculosis) after a few months or even years, which is characterized by extensive tissue necrosis, for example pulmonary caverns. The specific immunity and allergy that develop in the course of an infection reflect T lymphocyte functions. The allergy is measured in terms of the tuberculin reaction to check for clinically inapparent infections with TB. Diagnosis of tuberculosis requires identification of the pathogen by means of microscopy and culturing. Modern molecular methods are now coming to the fore in TB detection. Manifest tuberculosis is treated with two to four anti- tubercule chemotherapeutics in either a short regimen lasting six months or a standard regimen lasting nine months.

In contrast toTB, the LB pathogens do not lend themselves to culturing on artificial nutrient mediums. Leprosy is manifested mainly in skin, mucosa, and nerves. In clinical terms, there is a (malignant) lepromatous type leprosy and a (benign) tuberculoid type. Nondifferential forms are also frequent. Humans are the sole infection reservoir. Transmission of the disease is by close contact with skin or mucosa.

The genus Mycobacterium belongs to the Mycobacteriaceae family. This genus includes saprophytic species that are widespread in nature as well as the causative pathogens of the major human disease complexes tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacteria are Gram-positive, although they do not take gram staining well. The explanation for this is a cell wall structure rich in lipids that does not allow the alkaline stains to penetrate well. At any rate, once mycobacteria have been stained (using radical methods), they resist destaining, even with HCl-alcohol. This property is known as acid fastness.

Tuberculosis Bacteria (TB)

History. The tuberculosis bacteria complex includes the species Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis, and the rare species M. africanum. The clinical etiology of tuberculosis, a disease long known to man, was worked out in 1982 by R. Koch based on regular isolation of pathogens from lesions. Tuberculosis is unquestionably among the most intensively studied of all human diseases. In view of the fact that tuberculosis can infect practically any organ in the body, it is understandable why a number of other clinical disciplines profit from these studies in addition to microbiology and pathology.

Morphology and culturing. TB are slender, acid-fast rods, 0.4 µm wide, and 3-4 µm long, nonsporing and nonmotile. They can be stained with special agents (Fig. 4.12a).

TB are obligate anaerobes. Their reproduction is enhanced by the presence of 5-10% CO2 in the atmosphere. They are grown on culture mediums with a high lipid content, e.g., egg-enriched glycerol mediums according to Lowen- stein-Jensen (Fig. 4.12b). The generation time of TB is approximately 12-18 hours, so that cultures must be incubated for three to six or eight weeks at 37 °C until proliferation becomes macroscopically visible.

Cell wall. Many of the special characteristics of TB are ascribed to the chemistry of their cell wall, which features a murein layer as well as numerous lipids, the most important being the glycolipids (e.g., lipoarabinogalactan), the mycolic acids, mycosides, and wax D.

Glycolipids and wax D.

- Responsible for resistance to chemical and physical noxae.

- Adjuvant effect (wax D), i.e., enhancement of antigen immunogenicity.

- Intracellular persistence in nonactivated macrophages by means of in-hibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion.

- Complement resistance.

- Virulence. Cord factor (trehalose 6,6-dimycolate).

Tuberculoproteins.

- Immunogens. The most important of these is the 65 kDa protein.

- Tuberculin. Partially purified tuberculin contains a mixture of small proteins (10 kDa). Tuberculin is used to test for TB exposure. Delayed allergic reaction.

Polysaccharides. Of unknown biological significance.

Pathogenesis and clinical picture. It is necessary to differentiate between primary and secondary tuberculosis (reactivation or postprimary tuberculosis) (Fig. 4.13). The clinical symptoms are based on reactions of the cellular immune system with TB antigens.

- Primary tuberculosis. In the majority of cases, the pathogens enter the lung in droplets, where they are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. TB bacteria are able to reproduce in these macrophages due to their ability to inhibit formation of the phagolysosome. Within 10-14 days a reactive inflammatory focus develops, the so-called primary focus from which the TB bacteria move into the regional hilar lymph nodes, where they reproduce and stimulate a cellular immune response, which in turn results in clonal expansion of specific T lymphocytes and attendant lymph node swelling. The Ghon's complex (primary complex, PC) develops between six and 14 weeks after infection. At the same time, granulomas form at the primary infection site and in the affected lymph nodes, and macrophages are activated by the cytokine MAF (macrophage activating factor). A tuberculin allergy also develops in the macroorganism.

The further course of the disease depends on the outcome of the battle between the TB and the specific cellular immune defenses. Post primary dissemination foci are sometimes observed as well, i.e., development of local tissue defect foci at other localizations, typically the apices of the lungs. Mycobacteria may also be transported to other organs via the lymph vessels or bloodstream and produce dissemination foci there. The host eventually prevails in over 90% of cases: the granulomas and foci fibrose, scar, and calcify, and the infection remains clinically silent.

- Secondary tuberculosis. In about 10% of infected persons the primary tuberculosis reactivates to become an organ tuberculosis, either within months (5%) or after a number of years (5%). Exogenous reinfection is rare in the populations of developed countries. Reactivation begins with a caseation necrosis in the center of the granulomas (also called tubercles) that may progress to cavitation (formation of caverns). Tissue destruction is caused by cytokines, among which tumor necrosis factor a (TNFa) appears

to play an important role. This cytokine is also responsible for the cachexia associated with tuberculosis. Reactivation frequently stems from old foci in the lung apices.

The body's immune defenses have a hard time containing necrotic tissue lesions in which large numbers of TB cells occur (e.g., up to 109 bacteria and more per cavern); the resulting lymphogenous or hematogenous dissemination may result in infection foci in other organs. Virtually all types of organs and tissues are at risk for this kind of secondary TB infection. Such infection courses are subsumed under the term extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

Immunity. Humans show a considerable degree of genetically determined resistance to TB. Besides this inherited faculty, an organism acquires an (incomplete) specific immunity during initial exposure (first infection). This acquired immunity is characterized by localization of the TB at an old or new infection focus with limited dissemination (Koch's phenomenon). This immunity is solely a function of the T lymphocytes. The level of immunity is high while the body is fending off the disease, but falls off rapidly afterwards. It is therefore speculated that resistance lasts only as long as TB or the immunogens remain in the organism (= infection immunity).

Tuberculin reaction. Parallel to this specific immunity, an organism infected with TB shows an altered reaction mechanism, the tuberculin allergy, which also develops in the cellular immune system only. The tuberculin reaction, positive six to 14 weeks after infection, confirms the allergy. The tuberculin proteins are isolated as purified tuberculin (PPD = purified protein derivative). Five tuberculin units (TU) are applied intracutaneously in the tuberculin test (Mantoux tuberculin skin test, the “gold standard”). If the reaction is negative, the dose is sequentially increased to 250 TU. A positive reaction appears within 48 to 72 hours as an inflammatory reaction (induration) at least 10 mm in diameter at the site of antigen application. A positive reaction means that the person has either been infected with TB or vaccinated with BCG. It is important to understand that a positive test is not an indicator for an active infection or immune status. While a positive test person can be assumed to have a certain level of specific immunity, it will by no means be complete. One-half of the clinically manifest cases of tuberculosis in the population are secondary reactivation tuberculoses that develop in tuberculin- positive persons.

Diagnosis requires microscopic and cultural identification of the pathogen or pathogen-specific DNA.

Traditional method

- Workup of test material, for example with N-acetyl-L-cysteine-NaOH (NALC-NaOH method) to liquefy viscous mucus and eliminate rapidly prolif-

erating accompanying flora, followed by centrifugation to enrich the concentration.

- Microscopy. Ziehl-Neelsen and/or auramine fluorescent staining . This method produces rapid results but has a low level of sensitivity (>104-105/ml) and specificity (acid-fast rods only).

- Culture on special solid and in special liquid mediums. Time requirement: four to eight weeks.

- Identification. Biochemical tests with pure culture if necessary. Time re-quirement: one to three weeks.

- Resistance test with pure culture. Time requirement: three weeks.

Rapid methods. A number of different rapid TB diagnostic methods have been introduced in recent years that require less time than the traditional methods.

- Culture. Early-stage growth detection in liquid mediums involving identification of TB metabolic products with highly sensitive, semi-automated equipment. Time requirement: one to three weeks. Tentative diagnosis.

- Identification. Analysis of cellular fatty acids by means of gas chromatography and of mycolic acids by means of HPLC. Time requirement: 12 days with a pure culture.

- DNA probes. Used to identify M. tuberculosis complex and other mycobacteria. Time requirement: several hours with a pure culture.

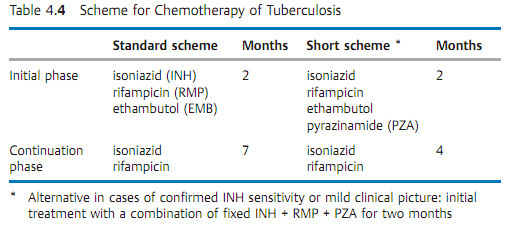

- Resistance test. Use of semi-automated equipment (see above). Proliferation/nonproliferation determination in liquid mediums containing standard antituberculotic agents (Table 4.4). Time requirement: 7-10 days.

Direct identification in patient material. Molecular methods used for direct detection of the M. tuberculosis complex in (uncultured) test material. These methods involve amplification of the search sequence.

Therapy. The previous method of long-term therapy in sanatoriums has been replaced by a standardized chemotherapy (see Table 4.4 for examples), often on an outpatient basis.

Epidemiology and prevention. Tuberculosis is endemic worldwide. The disease has become much less frequent in developed countries in recent decades, where its incidence is now about five to 15 new infections per 100 000 inhabitants per year and mortality rates are usually below one per 100 000 inhabitants per year. Seen from a worldwide perspective, however, tuberculosis is still a major medical problem. It is estimated that every year approximately 15 million persons contract tuberculosis and that three million die of the disease. The main source of infection is the human carrier. There are no healthy carriers. Diseased cattle are not a significant source of infection in the developed world. Transmission of the disease is generally direct, in most cases by droplet infection. Indirect transmission via dust or milk (udder tuberculosis in cattle) is the exception rather than the rule. The incubation period is four to 12 weeks.

- Exposure prophylaxis. Patients with open tuberculosis must be isolated during the secretory phase. Secretions containing TB must be disinfected. Tu-berculous cattle must be eliminated.

- Disposition prophylaxis. An active vaccine is available that reduces the risk of contracting the disease by about one-half. It contains the live vaccine BCG (lyophilized bovine TB of the Calmette-Gueirin type). Vaccination of tuberculin-negative persons induces allergy and (incomplete) immunity that persist for about five to 10 years. In countries with low levels of tuberculosis prevalence, the advisory committees on immunization practices no longer recommend vaccination with BCG, either in tuberculin-negative children at high risk or in adults who have been exposed to TB. Preventive chemotherapy of clinically in apparent infections (latent tuberculosis bacteria infection, LTBI) with INH (300 mg/d) over a period of six months has proved effective in high-risk persons, e.g., contact persons who therefore became tuberculin-positive, in tuberculin-positive persons with increased susceptibility (immunosuppressive therapy, therapy with corticosteroids, diabetes, alcoholism) and in persons with radiological confirmed residual tuberculosis. Compliance with the therapeutic regimen is a problem in preventive chemotherapy.

Leprosy Bacteria (LB)

Morphology and culture. Mycobacterium leprae (Hansen, 1873) is the causative pathogen of leprosy. In morphological terms, these acid-fast rods are identical to tuberculosis bacteria. They differ, however, in that they cannot be grown on nutrient mediums or in cell cultures.

Pathogenesis. The pathomechanisms of LB are identical to those of TB. The host organism attempts to localize and isolate infection foci by forming granulomas. Leprous granulomas are histopathologically identical to tuberculous granulomas. High counts of leprosy bacteria are often found in the macrophages of the granulomas.

Immunity. The immune defenses mobilized against a leprosy infection are strictly of the cellular type. The lepromin skin test can detect a postinfection allergy. This test is not, however, very specific (i.e., positive reactions in cases in which no leprosy infection is present). The clinically differentiated infection course forms observed are probably due to individual immune response variants.

Clinical picture. Leprosy is manifested mainly on the skin, mucosa, and pe-ripheral nerves.

A clinical differentiation is made between tuberculoid leprosy (TL, Fig. 4.14) and lepromatous leprosy (LL, Fig. 4.15). There are many intermediate forms. TL is the benign, nonprogressive form characterized by spotty dermal lesions. The LL form, on the other hand, is characterized by a malignant, progressive course with nodular skin lesions and cordlike nerve thickenings that finally lead to neuroparalysis. The inflammatory foci contain large numbers of leprosy bacteria.

Diagnosis. Detection of the pathogens in skin or nasal mucosa scrapings under the microscope using Ziehl-Neelsen staining . Molecular confirmation of DNA sequences specific to leprosy bacteria in a polymerase chain reaction is possible.

Therapy. Paucibacillary forms are treated with dapson plus rifampicin for six months. Multibacillary forms require treatment with dapson, rifampicin, and clofazimine over a period of at least two years.

Epidemiology and prevention. Leprosy is now rare in socially developed countries, although still frequent in developing countries. There are an estimated 11 million victims worldwide. Infected humans are the only source of infection. The details of the transmission pathways are unknown. Discussion of the topic is considering transmission by direct contact with skin or mucosa injuries and aerogenic transmission. The incubation period is 2-5-20 years. Isolation of patients under treatment is no longer required. An effective epidemiological reaction requires early recognition of the disease in contact person’s by means of periodical examinations every six to 12 months up to five years following contact.

Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM)

Mycobacteria that are neither tuberculosis nor leprosy bacteria are categorized as atypical mycobacteria (old designation), nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) or MOTT (mycobacteria other than tubercle bacilli).

Morphology and culture. In their morphology and staining behavior, NTM are generally indistinguishable from tuberculosis bacteria. With the exception of the rapidly growing NTM, their culturing characteristics are also similar to TB. Some species proliferate only at 30 °C. NTM are frequent inhabitants of the natural environment (water, soil) and also contribute to human and animal mucosal flora. Most of these species show resistance to the antituberculoid agents in common use.

Clinical pictures and diagnosis. Some NTM species are apathogenic, others can cause mycobacterioses in humans that usually follow a chronic course (Table 4.5). NTM infections are generally rare. Their occurrence is encouraged by compromised cellular immunity. Frequent occurrence is observed together with certain malignancies, in immunosuppressed patients and in AIDS patients, whereby the NTM isolated in 80% of cases are M. avium or M. intercellulare. As a rule, NTM infections are indistinguishable from tuberculous lesions in clinical, radiological, and histological terms. Diagnosis therefore requires culturing and positive identification. The clinical significance of a positive result is difficult to determine due to the ubiquitous occurrence of these pathogens. They are frequent culture contaminants. Only about 10% of all persons in whom NTM are detected actually turn out to have a mycobacteriosis.

Therapy. Surgical removal of the infection focus is often indicated. Chemotherapy depends on the pathogen species, for instance a triple combination (e.g., INH, ethambutol, rifampicin) or, for resistant strains, a combination of four or five antituberculoid agents.

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)