علم الكيمياء

تاريخ الكيمياء والعلماء المشاهير

التحاضير والتجارب الكيميائية

المخاطر والوقاية في الكيمياء

اخرى

مقالات متنوعة في علم الكيمياء

كيمياء عامة

الكيمياء التحليلية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء التحليلية

التحليل النوعي والكمي

التحليل الآلي (الطيفي)

طرق الفصل والتنقية

الكيمياء الحياتية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الحياتية

الكاربوهيدرات

الاحماض الامينية والبروتينات

الانزيمات

الدهون

الاحماض النووية

الفيتامينات والمرافقات الانزيمية

الهرمونات

الكيمياء العضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الهايدروكاربونات

المركبات الوسطية وميكانيكيات التفاعلات العضوية

التشخيص العضوي

تجارب وتفاعلات في الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء الحرارية

حركية التفاعلات الكيميائية

الكيمياء الكهربائية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الجدول الدوري وخواص العناصر

نظريات التآصر الكيميائي

كيمياء العناصر الانتقالية ومركباتها المعقدة

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

كيمياء النانو

الكيمياء السريرية

الكيمياء الطبية والدوائية

كيمياء الاغذية والنواتج الطبيعية

الكيمياء الجنائية

الكيمياء الصناعية

البترو كيمياويات

الكيمياء الخضراء

كيمياء البيئة

كيمياء البوليمرات

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الصناعية

الكيمياء الاشعاعية والنووية

Sequence Rules for Specifying Configuration

المؤلف:

John McMurry

المصدر:

Organic Chemistry

الجزء والصفحة:

9th - p124

31-5-2016

2933

Sequence Rules for Specifying Configuration

Structural drawings provide a visual representation of stereochemistry, but a written method for indicating the three-dimensional arrangement, or configuration, of substituents at a chirality center is also needed. This method employs a set of sequence rules to rank the four groups attached to the chirality center and then looks at the handedness with which those groups are attached. Called the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog rules after the chemists who proposed them, the sequence rules are as follows:

Rule 1

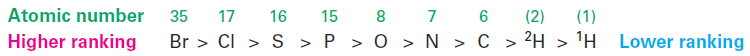

Look at the four atoms directly attached to the chirality center, and rank them according to atomic number. The atom with the highest atomic number has the highest ranking (first), and the atom with the lowest atomic number (usually hydrogen) has the lowest ranking (fourth). When different isotopes of the same element are compared, such as deuterium (2H) and protium (1H), the heavier isotope ranks higher than the lighter isotope. Thus, atoms commonly found in organic compounds have the following order.

Rule 2

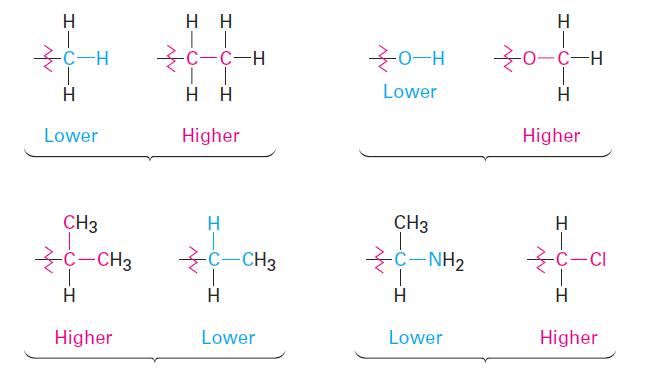

If a decision can’t be reached by ranking the first atoms in the substituent, look at the second, third, or fourth atoms away from the chirality center until the first difference is found. A -CH2CH3 substituent and a -CH3 substituent are equivalent by rule 1 because both have carbon as the first atom. By rule 2, however, ethyl ranks higher than methyl because ethyl has a carbon as its highest second atom, while methyl has only hydrogen as its second atom. Look at the following pairs of examples to see how the rule works:

Rule 3

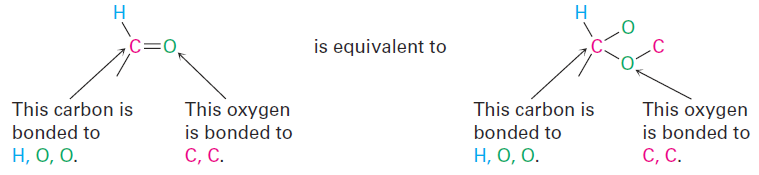

Multiple-bonded atoms are equivalent to the same number of singlebonded atoms. For example, an aldehyde substituent (-CH=O), which has a carbon atom doubly bonded to one oxygen, is equivalent to a substituent having a carbon atom singly bonded to two oxygens:

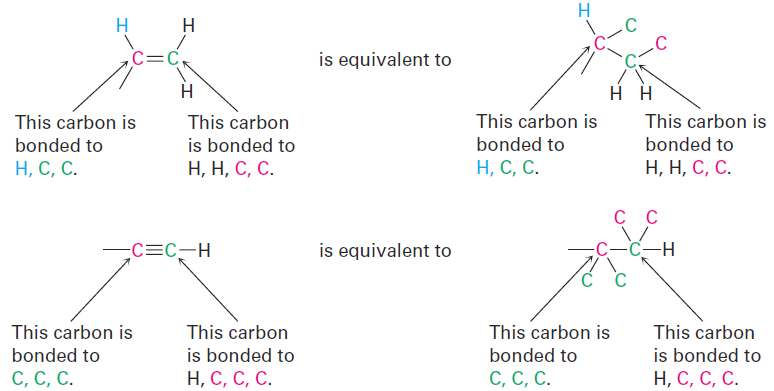

As further examples, the following pairs are equivalent:

Having ranked the four groups attached to a chiral carbon, we describe the stereochemical configuration around the carbon by orienting the molecule so that the group with the lowest ranking (4) points directly away from us. We then look at the three remaining substituents, which now appear to radiate toward us like the spokes on a steering wheel (Figure 1-1). If a curved arrow drawn from the highest to second-highest to third-highest ranked substituent (1→2→3) is clockwise, we say that the chirality center has the R configuration (Latin rectus, meaning “right”). If an arrow from 1 → 2 → 3 is counterclockwise, the chirality center has the S configuration (Latin sinister, meaning “left”). To remember these assignments, think of a car’s steering wheel when making a Right (clockwise) turn.

Figure 1-1 Assigning configuration to a chirality center. When the molecule is oriented so that the lowest-ranked group (4) is toward the rear, the remaining three groups radiate toward the viewer like the spokes of a steering wheel. If the direction of travel 1 → 2 →3 is clockwise (right turn), the center has the R configuration. If the direction of travel 1 → 2 → 3 is counterclockwise (left turn), the center is S.

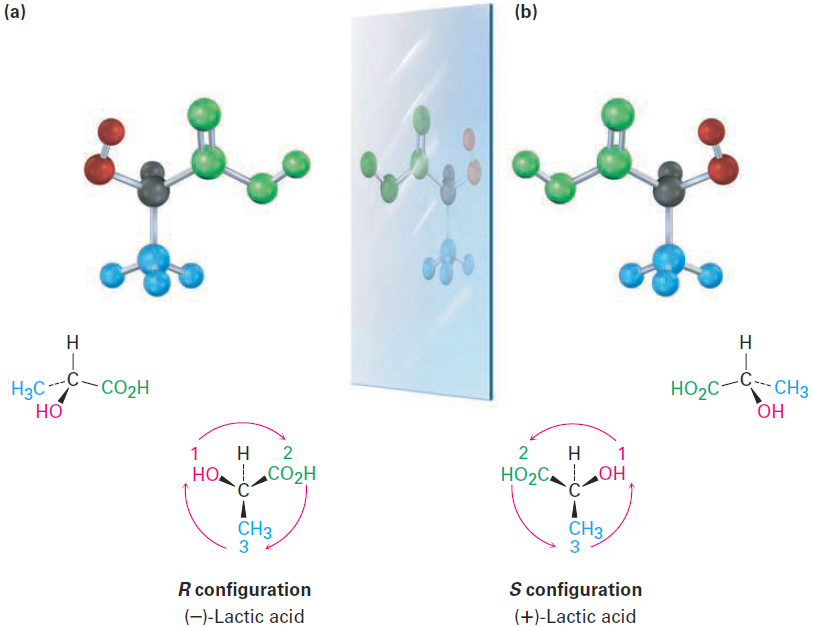

Look at (-)-lactic acid in Figure 1-2 for an example of how to assign configuration. Sequence rule 1 says that -OH is ranked 1 and -H is ranked 4, but it doesn’t allow us to distinguish between -CH3 and -CO2H because both groups have carbon as their first atom. Sequence rule 2, however, says that- CO2H ranks higher than -CH3 because O (the highest second atom in -CO2H) outranks H (the highest second atom in -CH3). Now, turn the molecule so that the fourth-ranked group ( -H) is oriented toward the rear, away from the observer. Since a curved arrow from 1 (- OH) to 2 (-CO2H) to 3 ( -CH3) is clockwise (right turn of the steering wheel), (-)-lactic acid has the R configuration. Applying the same procedure to (+)-lactic acid leads to the opposite assignment.

Figure 1-2 Assigning configuration to (a) (R)-(-)-lactic acid and (b) (S)-(+)-lactic acid.

Further examples are provided by naturally occurring (-)-glyceraldehyde and (1)-alanine, which both have the S configuration as shown in Figure 1-3. Note that the sign of optical rotation, (+) or (-), is not related to the R,S designation. (S)-Glyceraldehyde happens to be levorotatory (-), and (S)-alanine happens to be dextrorotatory (+). There is no simple correlation between R,S configuration and direction or magnitude of optical rotation.

Figure 1-3 Assigning configuration to (a) (-)-glyceraldehyde. (b) (+)-alanine. Both happen to have the S configuration, although one is levorotatory and the other is dextrorotatory.

One additional point needs to be mentioned—the matter of absolute configuration. How do we know that the assignments of R and S configuration are correct in an absolute, rather than a relative, sense? Since we can’t see the molecules themselves, how do we know that the R configuration belongs to the levorotatory enantiomer of lactic acid? This difficult question was finally solved in 1951, when an X-ray diffraction method was found for determining the absolute spatial arrangement of atoms in a molecule. Based on those results, we can say with certainty that the R,S conventions are correct.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)