النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Internal Structure of Roots

المؤلف:

AN INTRODUCTION TO PLANT BIOLOGY-1998

المصدر:

JAMES D. MAUSETH

الجزء والصفحة:

13-11-2016

5288

Internal Structure of Roots

ROOT CAP

To remain in place and provide effective protection for the root apical meristem, the root cap must have a specific structure and growth pattern. The cells in the layer closest to the root meristem are also meristematic, undergoing cell division with transverse walls and forming files of cells that are pushed forward (Fig. 1). Simultaneously, the cells on the edges of this group grow toward the side and proliferate. Although the cells appear to extend around the sides of the root, the root is actually growing through the edges of the root cap.

FIGURE 1: In the root cap, cells in the central portion (A) divide so that the two daughter cells are aligned with the root and the root cap grows forward. On the edges (B), cells divide and expand in such a way that cells flow radially outward.

Cells are small and meristematic when first formed at the base of the root cap, but as they are pushed forward, they develop dense starch grains and their endoplasmic reticulum becomes displaced to the forward end of the cell . These cells are capable of detecting gravity because the dense starch grains settle to the lower side of the cell.

As the cells are pushed closer to the edge of the cap, their structure and metabolism change dramatically. Endoplasmic reticulum becomes less conspicuous, starch grains are digested, and the cell's dictyosomes secrete copious amounts of mucigel by exocytosis. Simultaneously, the middle lamella breaks down and releases cells into the mucigel which are usually crushed by the expansion of the root. It has been estimated that only 4 or 5 days pass from cell formation in the root cap to its sloughing off. Consequently, the cap is constantly regenerating itself. A dynamic equilibrium must be maintained between these two processes.

ROOT APICAL MERISTEM

If the root apical meristem is examined in relation to the root tissues it produces, regular files of cells can be seen to originate in the meristem and extend into the regions of mature root tissues . The root is more orderly than the shoot because it experiences no disruptions due to leaf primordia, leaf traces, or axillary buds. Because the cell files extend almost to the center of the meristem, one might assume that cell divisions are occurring throughout it. However, use of a radioactive precursor of DNA, such as tritiated thymidine, can demonstrate that the central cells are not synthesizing DNA; their nuclei do not take up the thymidine and become radioactive (Fig. 2). This mitotically inactive central region is known as the quiescent center. These cells are more resistant to various types of harmful agents such as radiation and toxic chemicals, and it is now believed that they act primarily as a reserve of healthy cells. If part of the root apical meristem or root cap is damaged, quiescent center cells become active and form a new apical meristem. Once the new meristem is established, its central cells become inactive, forming a new quiescent center. Such a replacement mechanism is extremely important because the root apex is probably damaged frequently by various agents—sharp objects, burrowing animals, nematodes, and pathogenic fungi.

FIGURE 2:These roots were grown briefly in a solution of tritiated thymidine, a radioactive precursor of DNA. In cells that were undergoing the cell cycle, during S phase the radioactive thymidine w® incorporated into the nuclei. After a few hours, the root was killed, sliced into sections, and piaced on photographic film in the dark. The radioactive nuclei caused black spots to form in the film next to the nuclei. The slide was then given a brief exposure to light so that the outlines of the cells and nuclei would be faintly visible (too much light would obscure the radioactivity-induced black spots). The quiescent center is the region where no nuclei became radioactive. Apparently no cell in the region passed through S phase while tritiated thymidine was available—these cells were in cell cycle arrest. (Courtesy of L. J. Feldman, University of California, Berkley)

ZONE OF ELONGATION

Just behind the root apical meristem itself is the region where the cells expand greatly; some meristematic activity continues, but mostly the cells are enlarging. This zone of elongation is similar to the shoot sub-apical meristem region. Cells begin to differentiate into a visible pattern, although none of the cells is mature. The outermost cells are protoderm and differentiate into the epidermis. In the center is the provascular tissue, cells that develop into primary xylem and primary phloem. As in the stem, protoxylem and protophloem, which form earliest, are closest to the meristem. Farther from the root tip, older, larger cells develop into metaxylem and metaphloem. Between the provascular tissue and the protoderm is a ground tissue, a rather uniform parenchyma that differentiates into the root cortex.

In the zone of elongation, the tissues are all quite permeable; minerals can penetrate deep into the root through the apoplast simply by diffusing along the thin, fully hydrated young walls and intercellular spaces. This zone is so short that little actual absorption occurs there, and much that is absorbed is probably used directly for the root's own growth.

ZONE OF MATURATION/ROOT HAIR ZONE

In the maturation zone, several important processes occur more or less simultaneously. Root hairs grow outward, greatly increasing absorption of water and minerals. In some electron micrographs, a thin cuticle appears to be present on root epidermal cells, but this may be just a layer of fats. The zone of elongation merges gradually with the zone of maturation; no distinct boundary exists because the differences between the two represent the gradual continued differentiation of the cells.

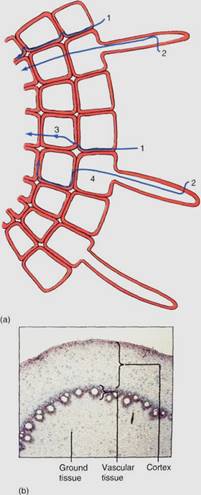

Although cortex cells continue to enlarge, their most significant activity is the transfer of minerals from the epidermis to the vascular tissue. This can be either by diffusion through the walls and intercellular spaces (called apoplastic transport) or by absorption into the cytoplasm of a cortical cell and then transferal from cell to cell, probably through plasmodesmata (symplastic transport; Fig. 3a). Cortical intercellular spaces are also important as an aerenchyma, allowing oxygen to diffuse throughout the root from the soil or stem (Fig. 3b).

FIGURE 3: (a) Many diffusion paths are possible through the root epidermis and outer cortex. 1 is entirely apoplastic: The water or mineral diffuses only through walls in intercellular spaces. 2 is symplastic transport: The material has passed through a plasma membrane and is now in the protoplasm. At 3, a molecule changes from the apoplast to the symplast, and at 4 the opposite occurs. (b) The cortex may be broad in many roots, and its interior boundary is the endodermis (X 15).

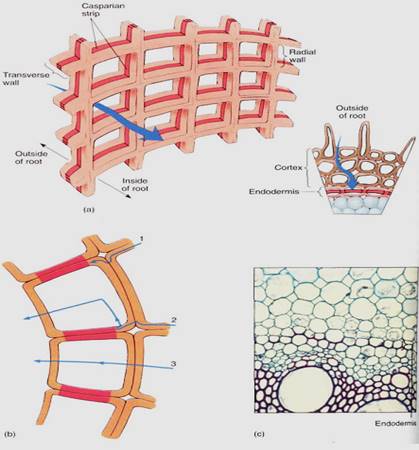

In the zone of maturation, minerals do not have free access to the vascular tissues because the innermost layer of cortical cells differentiates into a cylinder called the endodermis (Fig. 4). The cells of the endodermis have tangential walls, those closest to the vascular tissue or the cortex, which are ordinary thin primary walls. But their radial walls -the top, bottom, and side walls, that is, all the walls touching other endodermis cells— are encrusted with lignin and suberin, both of which cause the wall to be waterproof. The bands of altered walls, called Casparian strips, are involved in controlling the types of minerals that enter the xylem water stream. Cortex cells exert no control over the movement of minerals within intercellular spaces; without an endodermis, minerals of any type could move from the soil into the spaces, then into the xylem, and then into all parts of the plant. However, because Casparian strips are impermeable, minerals can cross the endodermis only if the endodermal protoplasts absorb them from the intercellular spaces of the cortex apoplasl or from cortical cells and then secrete them into the vascular tissues (Fig. 4b). Many harmful minerals can be excluded by the endodermis. It is not a perfect barrier against uncontrolled apoplastic movement, because in the zone of elongation, where the endodermis is not yet mature, minerals do have free access to the protoxylem, but this seems to represent only a low level of uncontrolled movement. Many glands and secretory cavities also have Casparian strips, which prevent the glands' secretory product from seeping into the surrounding tissues.

FIGURE 4 :(a) The endodermis is a cylinder, one layer of cells thick, each with Casparian strips. The best analogy is a brick chimney: It is a cylinder, one layer thick. The cement is analogous to the Casparian strips. (b) No apoplastic transport occurs across the endodermis. Materials that have been moving apoplastically (1) are stopped and can proceed farther only if the endodermis plasma membrane accepts them (2). Symplastic transport (3) is not affected. Plasma membranes that are impermeable to a particular type of molecule prevent that molecule from crossing the endodermis. (c) The endodermis in this corn is relatively easy to see: In all cells, Casparian strips are visible as red lines on the radial walls. In a few cells, only Casparian strips are present, but in many the radial walls and inner tangential walls have started to thicken; it is unusual for this development to start so early (X 200).

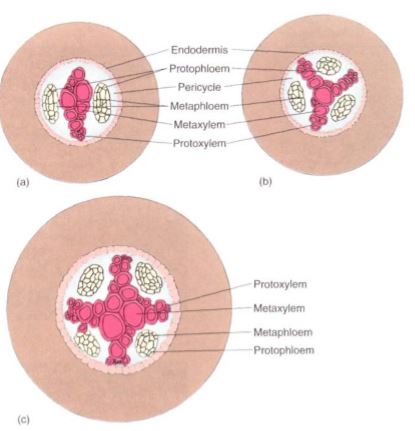

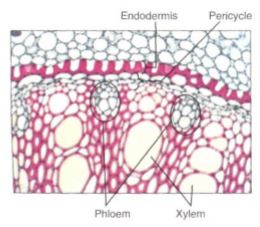

Within the vascular tissues, many of the much larger cells of the metaxylem and metaphloem become fully differentiated and functional in the zone of maturation. The arrangement of these tissues differs from that in stems: Instead of forming bundles containing xylem and phloem, the xylem of almost all plants except some monocots forms a solid mass in the center, surrounded by strands of phloem; no pith is present (Fig. 5a). In the roots of many monocots, strands of xylem and phloem are distributed in ground tissue (Fig. 5c).

FIGURE 5: (a) Low-magnification view and (b), high-magnification view of a transverse section of a root of buttercup, Ranunculus, showing the broad cortex and the small set of vascular tissues. The xylem has three sets of protoxylem, the narrow cells at the tips of the arms (b). The central, larger xylem cells are metaxylem. Three masses of phloem are also present; this is a triarch root. The endodermis is visible, but Casparian strips are difficult to see at this magnification. The pericycle is the set of cells between the endodermis and the vascular cells (a, X 50; b, X 250). (c) Low-magnification view and (d) high-magnification view of a transverse section of a root of Smilax. The vascular tissue of many monocot roots (such as this Smilax) consists of numerous large vessels and separate bundles of phloem. The endodermis is very easy to see (c, X 15; d, X 150).

Within the xylem, the inner wide cells are metaxylem and the outer narrow ones are protoxylem. Two to four or more groups of protoxylem may be present, the number being greater in larger roots with a wider mass of xylem (Fig. 6); the number of phloem strands equals the number of protoxylem strands. Within the phloem strands, protophloem is found on the outer side, and metaphloem on the inner side. Other than the arrangement, the vascular tissues of the root are similar to those of the stem and leaf. Those formed first are narrowest and most extensible, often finally being torn by the continued elongation and expansion of the cells around them. Those formed after the adjacent cells have stopped expanding are larger and, in the xylem, have heavier walls, often with bordered pits.

FIGURE 6: The number of strands of protoxylem in a root varies from one species to another and among the roots of one plant. Generally, wider, more robust roots have more protoxylem masses. Having two masses of protoxylem (and two of phloem) is diarch (a); three is triarch (b); and four is tetrarch (c).

Between the vascular tissue and the endodermis are parenchyma cells that constitute an irregular region called the pericycle . When lateral roots are produced, they are initiated in the pericycle.

MATURE PORTIONS OF THE ROOT

Root hairs function only for several days, after which they die and degenerate. Absorption of water and minerals in this area is then greatly reduced but does not stop entirely. Within the endodermis, the cells may remain unchanged, but usually there is a continued maturation in which a layer of suberin is applied over all radial surfaces, the inner tangential face, and sometimes even the outer tangential face. This can be followed by a layer of lignin and then more suberin (Fig.7). This is an irregular process, and some cells complete it earlier than others; thus in fairly mature parts of the root it is possible to find occasional cells that have only Casparian strips. These cells are called passage cells because they were once thought to represent passageways for the absorption of minerals; it is now suspected that they are merely slow to develop.

The result of the continued endodermis maturation is the formation of a watertight sheath around the vascular tissues. In the older parts of the root, it functions to keep water in The absorption of minerals in the root hair zone causes a powerful absorption of water , and a water pressure, called root pressure, builds up. If it were not for the mature endodermis, root pressure would force the water to leak out into the cortex of older parts of the root instead of moving up into the shoot. This is presumably also a function of the endodermis in rhizomes and stolons; if water leaked into the stem cortex and filled the intercellular spaces, oxygen diffusion would be prevented and the tissues would suffocate.

Many important events occur at the endodermis. The cortex and epidermis, aside from root hairs, may be superfluous, because shortly after the root hairs die, the cortex and epidermis often die also and are shed from the root. The endodermis becomes the root surface until a bark can form. This happens mostly in perennial roots that persist for several years. In apple trees, the cortex is shed as early as 1 week after the root hairs die, although it may persist for as long as 4 weeks; only the root tips have a cortex. The large fibrous roots of many monocots are strictly annual; they are replaced by new adventitious roots that form on new rhizomes or stolons. In these plants, the entire root dies.

FIGURE 7: The endodermis here is in its final stage of differentiation. All walls except the outer tangential ones have thickened so that almost no room remains for the protoplast. This endodermis effectively prevents water leakage from the vascular tissues into the cortex (X 180).

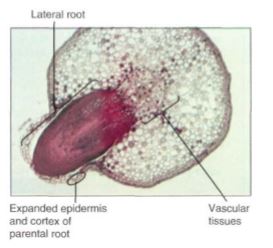

ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF LATERAL ROOTS

Lateral roots are initiated by cell divisions in the pericycle. Some cells become more densely cytoplasmic with smaller vacuoles and resume mitotic activity. The activity is localized to just a few cells, creating a small root primordium that organizes itself into a root apical meristem and pushes outward. As the root primordium swells into the cortex, the endodermis may be torn or crushed or may undergo cell division and form a thin covering over the primordium. As it pushes outward, the new lateral root destroys the cells of the cortex and epidermis that lie in its path, ultimately breaking the endodermis (Fig. 8). By the time the lateral root emerges, it has formed a root cap, and its first protoxylem and protophloem elements have begun to differentiate, establishing a connection to the vascular tissues of the parent root.

FIGURE 7.17 This young lateral root of willow (Salix) was initiated in the pericycle, next to a mass of protoxylem; its growth caused considerable damage to the parent root cortex, and it broke the surface open. Entry of pathogens is prevented by formation of wound bark around the tear it caused (X 50).

الاكثر قراءة في الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

الاكثر قراءة في الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)