تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

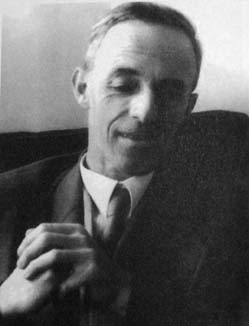

Wilhelm Süss

المؤلف:

S L Segal

المصدر:

Mathematicians under the Nazis

الجزء والصفحة:

...

16-8-2017

2058

Died: 21 May 1958 in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

Wilhelm Süss's mother came from a leading family, several members of which had become local mayors. Wilhelm's father was a school teacher and came from a musical family including professional musicians. Wilhelm inherited their love and talents for music. At his high school Wilhelm excelled in all his subjects and he had quite a difficult decision to make when entering university as to which subject he would study. He chose mathematics and entered Freiburg University where he was taught by Alfred Loewy.

It was the custom that students in Germany at this time did not remain at one university for their studies, but sampled the lectures at a number of different universities. Süss moved from Freiburg to Göttingen and then to Frankfurt, but before he could complete his studies World War I began and Süss was drafted into the army in October 1915. He fought on the front lines and was lucky to survive, contracting malaria from which he recovered in eight weeks. For a while he served as a veterinary assistant (due to an error in the information which the army held on his qualifications) but later he used his mathematical skills with a sound-ranging group. After three years of continuous service the war ended and he was demobilised in November 1918.

He returned to Frankfurt to complete his studies after this three year break, where his research in geometry was supervised by Bieberbach. Süss submitted his thesis Begründung der Inhaltslehre im Raum ohne Benutzung von Stetigkeitsaxiomen to Frankfurt in March 1920. At this time Süss met Irmgard Deckert, a mathematics student at the University and the daughter of a lecturer in geography. Later they married and we note that [13] and [14] are written by Irmgard Süss. In 1921 Bieberbach moved from Frankfurt to the University of Berlin where he was appointed to the chair of geometry. Süss moved from Frankfurt to Berlin to become Bieberbach's assistant but seems to have spent more time working for the German Mathematical Society than for Bieberbach.

In January 1923 Süss accepted a position in Kagoshima, Japan and began his new job in March. It was not really a mathematical job but rather saw Süss using his skills in German language and literature. He certainly did not abandon mathematics despite it not being part of his day to day work, and continued to undertake research which he published. After five years in Japan, Süss corresponded with Karl Reinhardt who was professor at Greifswald. The two had known each other from their childhood and the exchange of letters led to Reinhardt telling Süss that if he submitted his papers to Greifswald he could habilitate there and obtain a position. Süss accepted the idea and returned from Japan in 1928 to take up the lecturing post at Greifswald.

Hellmuth Kneser, the son of Adolf Kneser, had been appointed as professor at Greifswald three years before Süss came onto the staff there. The two soon became lifelong friends. This was a difficult time in Germany and Süss soon felt that the country was suffering unfairly. Although this led to him being a German Nationalist, he was certainly not a supporter of the National Socialist party at this time. His later associations with the Nazis is still a matter of considerable controversy among historians. For example Remmert (see [10] and [11]) is highly critical of the way that Süss worked with the Nazis, while Segal (see [1]) takes the view that Süss only cooperated with the Nazis as far as was necessary to protect mathematics. Supporters of each view can point to evidence to support their case and it is doubtful whether it will ever be possible to clarify Süss's motives.

On 30 January 1933 the National Socialist party led by Hitler came to power in Germany. In March all the teaching staff at Greifswald were forced to join the Sturmabteilung (Stormtroopers). Exemption was given to those who were members of the Stahlhelm, a veteran's organisation, so Süss joined the Stahlhelm. However on 3 July members of the Stahlhelm automatically became members of the Stormtroopers. In 1934 Alfred Loewy, Süss's former teacher, was dismissed from his chair at the University of Freiburg under the Nazi legislation dismissing Jews. Süss negotiated with the Ministry about succeeding Loewy and was appointed to the chair at Freiburg. According to Irmgard Süss, he began his discussions with the Ministry but making it clear that he was not a member of the Nazi party. At Freiburg Süss became a colleague of Doetsch and until 1940 the two were joint mathematical leaders of the university.

The German Mathematical Society became embroiled in political manoeuvrings after the National Socialists came to power. Bieberbach was unsuccessful in his attempt to become Chairman of the Society for life in 1934. After Blaschke and Hamel had served as Chairman, Süss was appointed in 1937. Some see his chairmanship as saving the German Mathematical Society, while others see it as a period when Süss enthusiastically cooperated with the National Socialists. Süss certainly initiated the expulsion of Jews from editorial boards, specifically asking that Issai Schur be removed from the board of Mathematische Zeitschrift in 1938. He joined the Nazi party in 1938 (Segal [1] claims he resisted but was persuaded by colleagues that he could act more effectively to change Nazi policies from within the party). He actively participated in the expulsion of non-Aryan German Mathematical Society members in 1938 and 1939 which led to the German Mathematical Society being successful in dealing with Nazi government officials. There is no doubt that during his period as Chairman, from 1938 to 1945, Süss worked in close collaboration with Nazi government officials. Among those who defend Süss's actions are Hildegard Abetz, Süss's daughter, and her husband [see P Abetz and H Abetz, Mitt. Dtsch. Math.-Ver. (4) 1999, 53]. They emphasise that things in the Third Reich were much more subtle than people who condemn Süss realise.

Today Süss is remembered as the creator of the Oberwolfach Mathematical Institute. In [14] Irmgard Süss writes that Süss had the idea for a Mathematical Institute for some time and felt that it should be based at Göttingen. Hasse wrote to Süss on 24 March 1944 suggesting he leave Freiburg and move to Göttingen. However Freiburg were keen to keep Süss who was at that time the most important figure in mathematical politics in Germany. Süss wrote (see [1]):-

The Ministry of Education of Baden, wanting to keep me in Freiburg at least in the present difficult situation, has offered me a place of rare advantages in the Black Forrest where I hope to start the most urgent work without delay and undisturbed.

On 3 August 1944 Hermann Göring authorised the creation of the Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach in a hunting lodge known as Lorenzenhof (named after the farm that it replaced) in the tiny village of Oberwolfach-Walke in the Black Forest. Jackson writes [5]:-

Of all the world's mathematics institutes the Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach is certainly one of the most beloved. Traditionally referred to simply as Oberwolfach ... the institute is perched on a hillside in a lovely valley of Germany's Black Forest.

There is no doubt that the creation of the Institute was agreed because the Nazis believed that mathematics was of military importance to Germany. Süss was not only the founded of the Institute but he became its first director. Senechal writes in [12]:-

Süss was Oberwolfach and Oberwolfach was Süss.

He took his family to Oberwolfach and together with mathematicians from military establishments and colleagues from Freiburg, including Behnke and Seifert, they made up a team of about twenty who lived there until the war ended [5]:-

Irmgard Süss's history tells a tale of courage and camaraderie in those final days; the problem of securing food and heating; the preparations for flight in case the Lorenzenhof was attacked; the eventual occupation of the lodge; and, once the war was officially over, the frantic burning of books on National Socialism that had been stored in the house.

Süss was suspended from his position at Freiburg at the end of the war. He kept his position as director of Oberwolfach, however. He was a member of the Nazi party who had a close association with party officials, but many letters of support from his colleagues stated that he never held Nazi beliefs and had only joined the party to help the cause of mathematics. Süss too claimed that he had always opposed Nazi policies and that he had supported colleagues suffering under Nazi policies. Letters from colleagues such as Carathéodory, Tietze, Hopf and Perron told of many colleagues who Süss had saved from political persecution. Süss was reinstated after two months, and Freiburg elected him Rector of the University in 1958. By this time, however, he was ill with liver cancer from which he died shortly afterwards.

It was due in large part to Süss's efforts that Oberwolfach flourished after the war ended [5]:-

The Institute lost its funding from the national government but was able to keep going with a small amount from the state government of Baden. Süss worked hard to make the Institute truly international. Indeed, Oberwolfach played an important role in the rebuilding of mathematics in Germany after the war by serving as a place for meetings between German mathematicians and their colleagues abroad. ...

From 1949 to 1953 three to five meetings were held every year; the number increased to about a dozen per year after Süss secured funding from the federal government.

Let us look at some of the mathematics which Süss produced, in particular examining papers which give results which are rather typical of his mathematical output. In 1947 Süss proved the following theorem in Kennzeichnende Eigenschaften der Kugel als Folgerung eines Brouwerschen Fixpunktsatzes. Let E be a convex body in three-space with the following property: to every direction y corresponds a plane normal to y, depending continuously on y, and intersecting E in a region B(y) such that all these regions B(y) are congruent. Then the regions B(y) are circles. In 1950 he proved in Bestimmung einer Fläche durch die dritte Grundform und die Summe der Hauptkrümmungsradien that a surface is uniquely determined if a strip, and (as functions of the parameters) the third fundamental form, i.e., the first fundamental form of the spherical image, and the sum of the principal radii of curvature, is given. In the same year he publishedEichflächenprinzipien in der projektiven Flächentheorie which aims to put in place the foundations of a general projective theory of surfaces in a manner roughly corresponding to Berwald's treatment of the Euclidean and affine case but strongly employing the methods of relative differential geometry.

The paper Eine elementare kennzeichnende Eigenschaft des Ellipsoids (1953) proves in an elementary way that an ovaloid, all of whose orthogonal projections are ellipses, is an ellipsoid. In 1954 Süss's paper Eine characteristische Eigenschaft der Ellipse proved the following theorem: Let M be a set of ovals equivalent to each other under the group of affine transformations, and let M have the property that any two of its members meeting in more than four points coincide. Then the ovals in M are ellipses. We should also mention Süss's work as an editor of Fundamentals of mathematics (first edition in German in 1958) which he worked on with Behnke, F Bachmann, K Fladt.

Books:

- S L Segal, Mathematicians under the Nazis (Princeton, NJ, 2003).

Articles:

- S Fudali, Hilbert's Third Problem (equality of volumes of two tetrahedra with equal altitudes and with equal areas of bases) (Polish), in Hilbert's Problems (Polish), Miedzyzdroje 1993 (Warsaw, 1997), 35-43.

- H Gericke, Wilhelm Süss, der Gründer des Mathematischen Forschungsinstitutes Oberwolfach, Jber. Deutsch. Math.-Verein 69 (4)1 (1967/1968), 161-183.

- H Gericke, Das Mathematische Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach, in Perspectives in mathematics (Basel, 1984), 23-39.

- A Jackson, Oberwolfach, yesterday and today, Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 47 (7) (2000), 758-765.

- H Mehrtens, The Gleichschaltung of mathematical societies in Nazi Germany, Math. Intelligencer 11 (3) (1989), 48-60.

- H Mehrtens, The Gleichschaltung of mathematical societies in Nazi Germany (German), in Jahrbuch Überblicke Mathematik (Mannheim, 1985), 83-103.

- V R Remmert, Ungleiche Partner in der Mathematik im 'Dritten Reich' : Heinrich Behnke und Wilhelm Süss, Math. Semesterber. 49 (1) (2002), 11-27.

- V R Remmert, Das Mathematische Institut der Universität Freiburg (1900-1950), in Mathematik im Wandel (Hildesheim, 2001), 374-392.

- V R Remmert, Mathematicians at war. Power struggles in Nazi Germany's mathematical community : Gustav Doetsch and Wilhelm Süss, Rev. Histoire Math. 5 (1) (1999), 7-59.

- V R Remmert, Griff aus dem Elfenbeinturm. Mathematik, Macht und Nationalsozialismus : das Beispiel Freiburg, Mitt. Dtsch. Math.-Ver. (3) (1999), 13-24.

- M Senechal, Oberwolfach, 1944-1964, Math. Intelligencer 20 (4) (1998), 17-24.

- I Süss, The mathematical research institute Oberwolfach through critical times, in General inequalities 3, Oberwolfach, 1981 (Basel, 1983), 3-17.

- I Süss, Origin of the Mathematical Research Institute Oberwolfach at the country seat 'Lorenzenhof', in General inequalities 2, Oberwolfach, 1978 (Basel-Boston, Mass., 1980), 3-13.

الاكثر قراءة في 1890to1894

الاكثر قراءة في 1890to1894

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)