النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 5-11-2015

Date: 21-7-2021

Date: 5-11-2015

|

Abdominal Wall

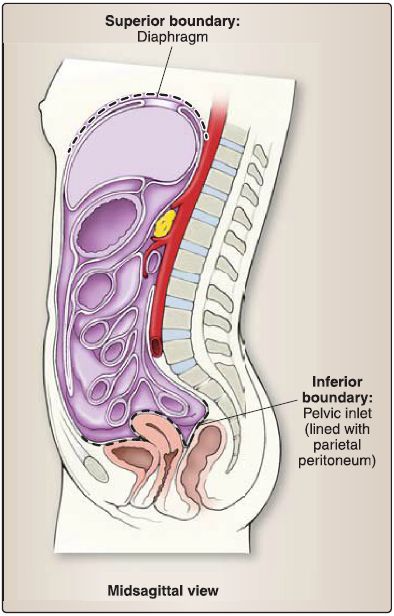

The abdomen represents the axial region that extends between the muscular diaphragm and the bony pelvis and contains important gastrointestinal (GI}, renal, and endocrine viscera and glands. It is characterized by a multilayered anterolateral muscular wall, which allows for varying degrees of expansion, and is lined internally by parietal and visceral peritoneum, thus creating a peritoneal cavity. Abdominal contents are partially protected by the bony thoracic cage superiorly and the bony pelvis inferiorly (Fig.1).

Figure .1: Abdomen boundaries.

For diagnostic and descriptive purposes, the abdomen can be divided into regions or quadrants externally, which allow for consistent anatomical localization internally. Nine topographic abdominal regions are bound by imaginary vertical lines through the midclavicular planes bilaterally and horizontal lines through subcostal and transtubercular planes. Quadrants are bound by an imaginary vertical line through the median plane and horizontal line through the transumbilical plane. The umbilicus is the most prominent external feature of the abdominal wall, located midway between the xiphoid process and pubic symphysis (Fig.2).

Figure .2 :Abdomen regional (A) and quadrant (B) organization. E = epigastric, LH = left hypogastric, LI = left inguinal, LL= left lateral (lumbar), LLQ = left lower quadrant, LUQ = left upper quadrant, P = pubic, RH = right hypogastric, RI = right inguinal, RL = right lateral (lumbar), RLQ = right lower quadrant, RUQ = right upper quadrant, U = umbilical.

A. Anterolateral abdominal wall

Unlike the thoracic wall, the anterolateral abdominal wall is primarily made up of layers of soft tissue, including fascia, adipose, muscle, and peritoneum. For descriptive purposes, these structures contribute to the lateral and anterior walls of the abdomen.

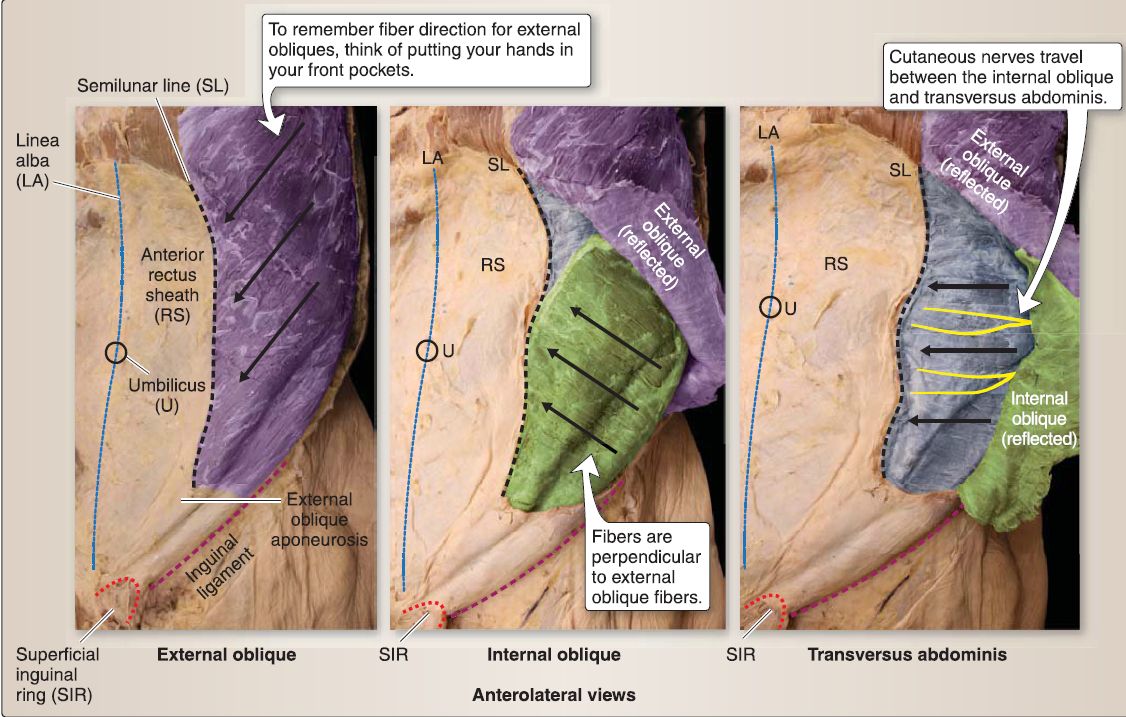

1. Lateral abdominal wall: Laterally, the abdominal wall is characterized by the layering of three flat abdominal muscles on either side-external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis (Fig.3). Collectively, these muscles provide support to pelvic viscera. External and internal oblique muscles also perform trunk rotation and flexion.

a. External oblique: This muscle originates from the external surfaces of ribs 5-12 and inserts onto the anterior iliac crest, pubic tubercle, and linea alba.

Figure 3: Lateral abdominal wall muscles. Left side of abdominal wall. Note arrows illustrate muscle fiber direction.

Figure 3: Lateral abdominal wall muscles. Left side of abdominal wall. Note arrows illustrate muscle fiber direction.

b. Internal oblique: This muscle originates from the iliac crest and thoracolumbar fascia and inserts onto the pectin pubis (by the conjoint tendon), linea alba, and ribs 10-12.

c. Transversus abdominis: This muscle originates from the internal surfaces of the costal cartilages associated with ribs 7-12, the iliac crest, and thoracolumbar fascia and inserts onto the pubic crest, pectin pubis (by the conjoint tendon), and linea alba.

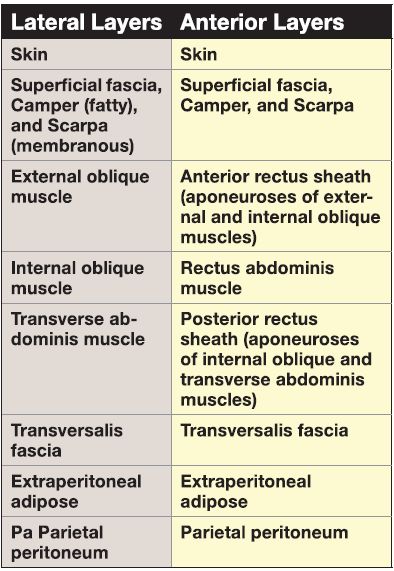

d. Layers: The general arrangement of layers from superficial to deep is presented in Table .1 .

Table 1: General Arrangement of Anterolateral Wall Layers From Superficial to Deep

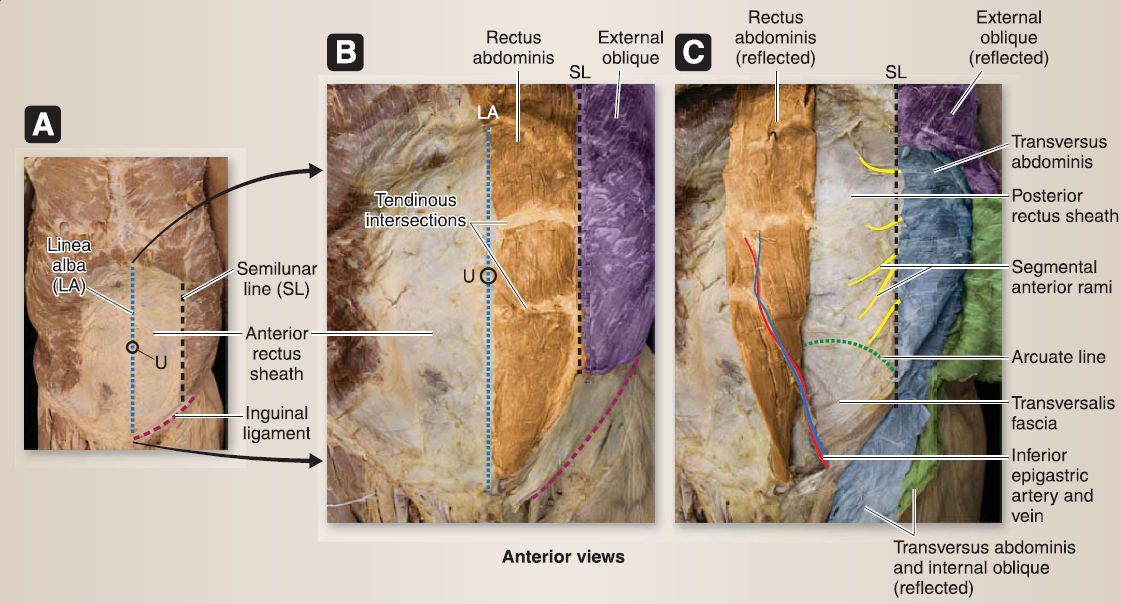

2. Anterior abdominal wall: Anteriorly, the abdominal wall is characterized by the umbilicus, rectus abdominis, and pyramidalis muscles; rectus sheath; and the midline linea alba (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 : Anterior abdominal wall structures. A, Rectus sheath intact. B, Left anterior rectus sheath removed to reveal rectus abdominis. C, Left rectus abdominis muscle reflected to right to reveal posterior rectus sheath and associated structures.

The rectus sheath is composed of the aponeuroses of the three flat muscles and encapsulates the rectus abdominis muscle and inferior epigastric arteries and veins. In conjunction with the lateral flat muscles, rectus abdominis flexes the trunk and provides support to abdominal viscera as well as aids in pelvic tilt control. It is characterized by perpendicular tendinous intersections along its length, which anchor the muscle to the internal surface of the anterior rectus sheath. Pyramidalis is considered insignificant in the support of the anterior wall, although it functions to tense the linea alba. It is often used as a landmark for abdominal surgeries.

a. Rectus abdominis: This muscle originates from the pubic crest and symphysis and inserts superiorly onto the xiphoid process and costal cartilages of ribs 5-7.

b. Pyramidalis: This muscle originates from the anterior pubis and pubic ligament and inserts in the linea alba.

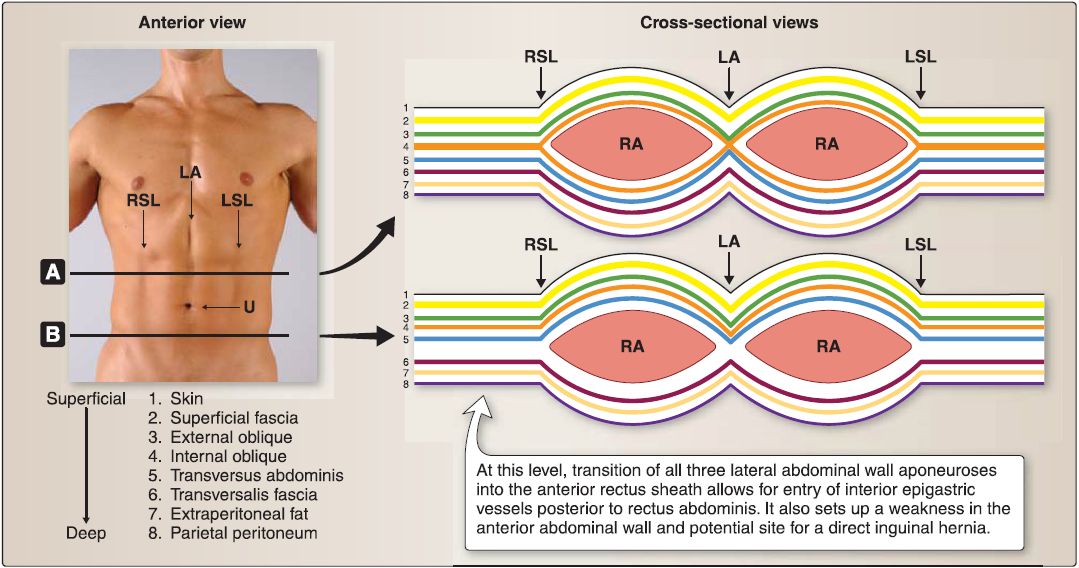

c. Layers: Anteriorly, the general arrangement of layers from superficial to deep is presented in Table .1. This arrangement changes at the midway point between the umbilicus and pubic symphysis, due to the transition of aponeuroses. At this level, all three aponeuroses travel anterior to the rectus abdominis muscle, leaving only the transversalis fascia to line the posterior surface of the muscle. This interruption in the dense connective tissue sheath not only allows for the transmission of inferior epigastric vessels, but also creates a weakness in the anterior body wall (Fig. 5).

Figure5: Anterolateral abdominal wall layers and rectus sheath. A, Cross section superior to umbilicus. B, Cross section inferior to arcuate line. LA = linea alba, LSL = left semilunar line, RA = rectus abdominis, RSL = right semilunar line, U = umbilicus.

Figure5: Anterolateral abdominal wall layers and rectus sheath. A, Cross section superior to umbilicus. B, Cross section inferior to arcuate line. LA = linea alba, LSL = left semilunar line, RA = rectus abdominis, RSL = right semilunar line, U = umbilicus.

3. Innervation: These muscles and the overlying skin and fascia receive innervation from segmental anterior rami from thoracic and upper lumber spinal nerves (T 6-T12, L1-L2)-

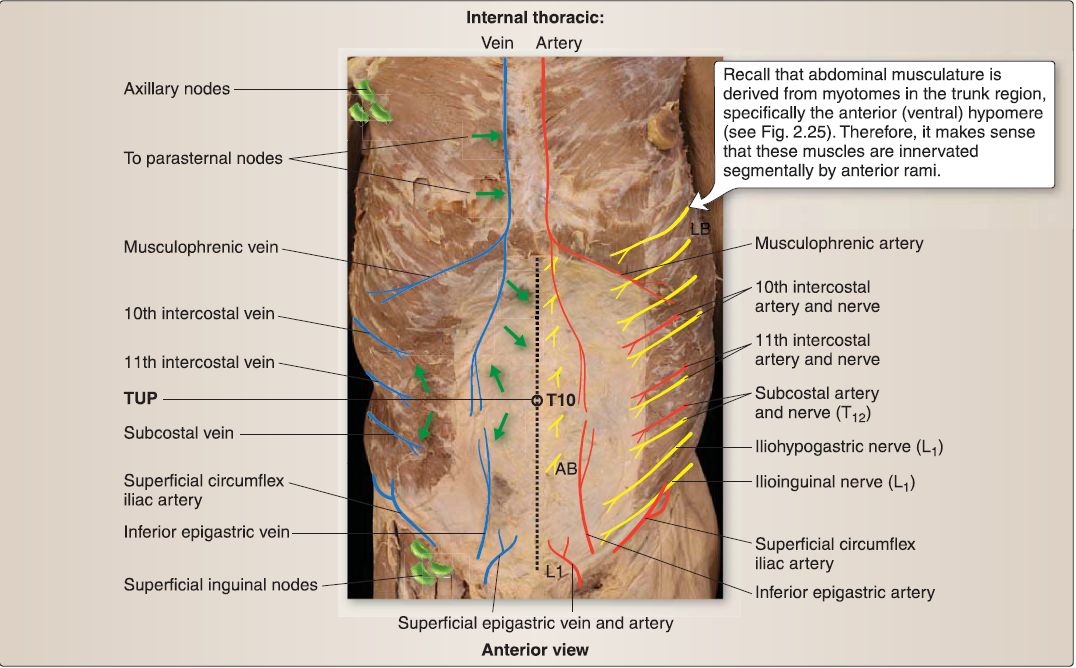

4. Blood supply and lymphatics: The abdominal wall has extensive venous, arterial, and lymphatic networks. This rich vascular arrangement provides important anastomotic flow to the region (Fig.6).

Figure 6: Abdominal wall blood supply and lymphatics. Right side shows arterial and nervous supply. Lett side shows venous drainage and direction of lymph drainage (green arrows). Superficial venous network not pictured. T10 marks the dermatome around the umbilicus. L 1 marks the dermatome at the pubic symphysis. AB = anterior branch of thoracoabdominal nerves, LB = lateral branch of thoracoabdominal nerves, TUP = transumbilical plane.

Figure 6: Abdominal wall blood supply and lymphatics. Right side shows arterial and nervous supply. Lett side shows venous drainage and direction of lymph drainage (green arrows). Superficial venous network not pictured. T10 marks the dermatome around the umbilicus. L 1 marks the dermatome at the pubic symphysis. AB = anterior branch of thoracoabdominal nerves, LB = lateral branch of thoracoabdominal nerves, TUP = transumbilical plane.

a. Veins: The venous plexus found in the subcutaneous tissue is made up of tributaries inferiorly from the femoral vein (superficial epigastric and superficial circumflex iliac) and external iliac vein (inferior epigastric), laterally from the axillary vein (lateral thoracic), superiorly from the superior epigastric/internal thoracic veins, and posteriorly from the 11th posterior intercostal and subcostal veins. Paraumbilical veins-tributaries from the hepatic portal vein-anastomose with the tributaries in the paraumbilical region to allow for important collateral flow if there is a blockage. This is one of a few areas in the body where there is a portal-caval anastomosis.

b. Arteries: The principle arterial supply for the anterolateral abdominal wall is maintained by branches of the internal thoracic (musculophrenic and superior epigastric), external iliac (inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac), and femoral (superficial circumflex iliac and superficial epigastric) arteries. Posterior intercostal (10th and 11th) and subcostal arteries- branches of the aorta-provide additional supply primarily to the lateral portion of the abdominal wall. The superior and inferior epigastric arteries pierce the rectus sheath to enter the space and supply the rectus abdominis muscle directly.

c. Lymphatics: Superficial lymphatic vessels superior to the transumbilical plane drain superiorly to axillary lymph nodes (primarily) and parasternal lymph nodes (secondarily). Superficial lymphatic vessels inferior to the transumbilical plane drain inferiorly into superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Deep lymphatic vessels travel with the network of deep veins and drain into lumbar, external iliac, and internal iliac nodes.

B. Inguinal region

The inguinal region lies along the inferior border of the anterolateral abdominal wall and represents the area of passageway (inguinal canal) for the testes/spermatic cord and round ligament of the uterus in the male and female, respectively.

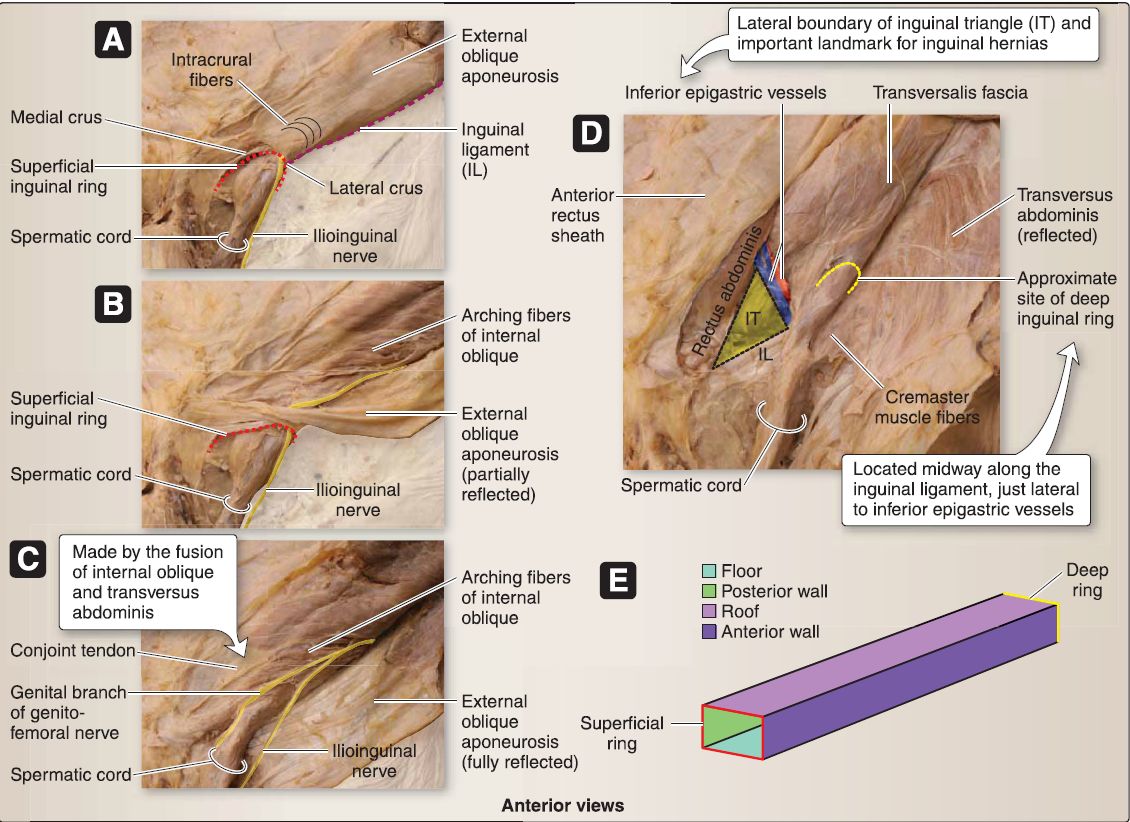

1. Inguinal canal: The inguinal canal is a passageway bounded by structures that make up the anterolateral abdominal wall. Imagine the canal as an oblique tunnel with two openings-a superficial inguinal ring (exit) and a deep inguinal ring (entrance). The superficial ring is framed by medial and lateral crural fibers and intracrural fibers that arise as an interruption of the external oblique aponeurosis. The deep ring is created by an invagination of transversalis fascia on the inner surface of the abdominal wall just lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. The boundaries of the inguinal canal are as follows (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Inguinal canal. Layers from superficial A to deep D (A-D). E. Schematic representation of inguinal canal boundaries.

a. Anterior: The anterior boundary of the inguinal canal is the external oblique aponeurosis.

b. Inferior (floor): The inguinal ligament (inferior border of the external oblique aponeurosis) and lacunar ligament (medial) comprise the inferior border.

c. Posterior: Posteriorly, the transversalis fascia and conjoint tendon border the inguinal canal.

d. Superior (roof): Arching fibers of internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles form the superior border.

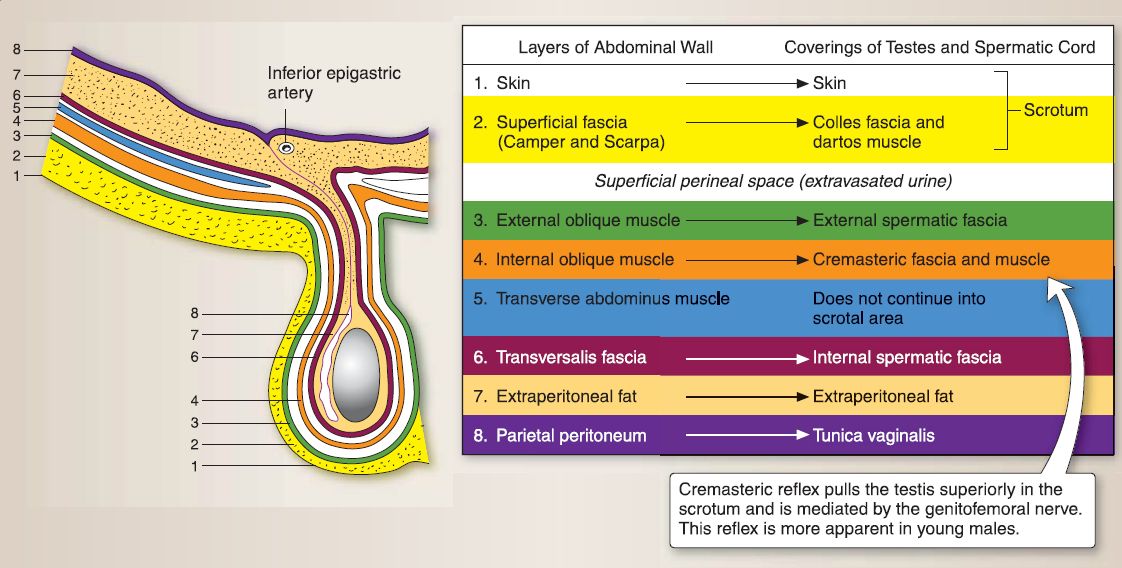

C. Spermatic cord and scrotum

Although considered part of the perineum, the scrotum is actually an extension of the lower abdominal wall (Fig. 8). Layers of the abdominal wall are represented in the scrotal region and form spermatic cord and testicular coverings. In addition to its coverings, the spermatic cord contains the ductus (vas) deferens, testicular artery, pampiniform venous plexus, deferential vessels, lymphatic vessels, autonomic nerves, and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (L1-L2).

Figure 8 : Scrotum. Corresponding abdominal wall and scrotal/spermatic cord layers.

|

|

|

|

لصحة القلب والأمعاء.. 8 أطعمة لا غنى عنها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حل سحري لخلايا البيروفسكايت الشمسية.. يرفع كفاءتها إلى 26%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جامعة الكفيل تحتفي بذكرى ولادة الإمام محمد الجواد (عليه السلام)

|

|

|